Author: Ildikó Heltai-Duffek

DOI: 10.5434/9789634902263/1

Abstract

This essay examines vocal genres at the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th, such as the villanella, aria, motet, madrigal and opera. The changing features of the genres, which include the monodic style and the recitative are at the centre of these changes. The features of the late Renaissance, for example, notation ornaments, and the Early Baroque period are beginning to be formed in those changes. By demonstrating these changes, the essay offers audiences and performers an opportunity to know and understand better the vocal music of this time and to perform it authenticly.

Keywords: monody, madrigal, motet, ornaments, Italy

Introduction

In the second half of the 16th century, various forms of art and behaviour were studied from a theoretical perspective in search of rules, laws, and proportions which would lead to the perfect performance, art piece, or behaviour. The investigations were based primarily on the culture of Ancient Greece. There was another aim from the perspective of music: the more exact and refined expression of various emotions and of the meaning in the text.

“[…] there exist discrete states known as fear, love, hate, anger, joy-to cite a few of the most common. From the last decades of the sixteenth century the arousal of the affections was considered the principal objective of poetry and music. There was much theorizing about the passions beginning about this time and continuing throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries” (Palisca, 1976, p.13).

The most important changes in pursuit of this objective occurred in the field of dissonances. Furthermore, the polyphonic linear and contrapuntal composition was gradually replaced by a chord-based approach, while monody, which is a monophonic vocal performance with accompanying chords, also emerged.

“In the last decades of the 16th century, special and increasing attention was focused among musicians in Rome, Florence, Ferrara, and Mantua on vocal performance with instrumental accompaniment and the aria-like melodic nature of certain voices in polyphonic works. […] The practice of solo singing, which used to occur in the context of improvisation and genres of minor importance, acquired prestige, became a highly artistic and expressive technique in certain circles of the cultural aristocracy, and almost exceeded the traditional and usual polyphonic practice in popularity” (Fabbri, 2007, p.12).

Among the antecedents of the emergence of monody, we find the occasional overcomplication of the musical material in polyphonic pieces, which made the words impossible to understand and follow. It was not uncommon that words which were independent, were of opposing meaning, or required distinct expression were sounded at the same time in different voices, which left little room for the unified expression of meaning. Based on Vincenzo Galilei’s writings, the remarks in relation to monody by Glenn Watkins address

“the inherent incompatibility of polyphony with the first-person emotionalism of the madrigal. In an effort to resolve this, monody was born” (Watkins, 1980, p.135).

At the same time, the use of basso continuo (that is to say, continuous bass accompaniment) began to spread gradually. With its popularity came the emergence of harmonic thinking instead of the prevailing polyphonic composition.

It was in the Cinquecento when the practice to depict words and textual content in an increasingly visual manner appeared. Madrigalism, also known as illustrative text depiction or text painting, was used by composers frequently in the period of polyphonic madrigals. For example, words such as “sky”, “high”, and “Sun” were usually sung in an upper register (sometimes the highest note of the melody fell on the listed words or on one of their syllables), while words such as “valley”, “night”, “dark”, and “death” were sung in a lower register, usually with longer rhythmic value, whereby the slow movement assisted the expression of the content. Words such as “pain” or “crying” were often assigned a chromatic step, whereas the word “merciless” is usually presented with a strong dissonance, especially after the last decade of the 16th century. Motifs with short interruptions were sometimes used to illustrate the word “sigh”. Quick passages were used to depict birdsong and words including “run”, “dance”, “chase”, “laugh”, “breeze”/“gust”, etc. Chords, including minor–major chord changes and dissonances, had a crucial role in text illustration. They were used to “paint” the meaning of certain words as well as to express the atmosphere of larger sections by the differentiated use of several registers, rhythmic values, dissonances, and voices. These musical devices are also easy to come by in the music of later periods and even of today.

In 16th-century Italy, listening to and performing music belonged to educated people’s popular pastimes. In the cities of the period, prominent families defined the political and musical scene: the Gonzagas in Mantua, the Estes in Ferrara, the Viscontis and Sforzas in Milan, and the Medicis in Florence. Isabella d’Este, Francesco Gonzaga’s wife, was famous for her knowledge and benefaction in relation to art. She was in correspondence with the greatest artists of the time: Leonardo da Vinci, Ariosto, Castiglione, and Titian. In addition, she was not an “outside spectator” to art: she created art herself according to the fashion in high society. In the pompous courts of sovereigns, art symbolised wealth. In affluent families, listening to music, playing instruments, and singing formed part of the everyday routine.

“The court attracted the intelligentsia and thus became one of the most important settings and displays of the cultural scene, which served as a model and was able to reproduce the world in which it was born” (Puskás, 1999, pp.35-36).

Noble benefactors often held a collection of scores and instruments. Princely and noble families often donated to other art forms besides music: paintings were ordered to adorn palaces, and artists at the court were also carefully selected. Besides decorating the walls, even instruments, among others, were embellished with paintings and carvings. Composers often received support for the publication of their works in print, which is why it was not uncommon to find the name of a prince or another nobleman on the cover as benefactor.

Artists, people of letters, scholars, theoreticians, and enthusiasts of the 16th and 17th century often formed academies. In their meetings, discussions were held about topical issues in science, philosophy, literature, or music, and courses were organised to those interested in literature and music, among others. Artists, writers, theoreticians, scholars were assisted both intellectually and financially, often through contributions to the publication of their works.

Count Giovanni Bardi’s house in Florence was home several gatherings between about 1573 and 1587 (the year when Bardi moved to Rome), where artists and theoreticians discussed the above-mentioned aesthetic questions in a similar way to academies. The circle was known as the Florentine Camerata or Camerata de’ Bardi. Later, the second Camerata was formed, hosted by Jacopo Corsi. Among others, Giulio Caccini and Jacopo Peri, two rivalling composers, were members in both. Opera-like genres of stage performance (“dramma per musica”, “favola in musica”) and even the genre of opera originated in the Camerata. Members of the society started out from drama performances of Ancient Greece, where poems were sung, and had the objective to implement this tradition in a modern setting (Orselli et al., 1986).

In the early 1600s, a public controversy ensued between Claudio Monteverdi and Giovanni Artusi about modern and traditional styles and devices of musical expression, in particular, about dissonance treatment. Artusi criticised the new style and especially Monteverdi’s madrigals in L’Artusi, overo Delle imperfettioni della moderna musica (“Artusi, or on the Imperfection of Modern Music”, 1600). Although Artusi did not mention the composer by name, the excerpts included in the book revealed the identity. It was only in 1605 when Monteverdi replied to the attack publicly, but only briefly, with the promise of an extensive defence of the “modern practice”, which was later published as Seconda pratica, overo Perfettione della musica moderna, that is, “Second Practice, or on the Perfection of Modern Music” (Palisca, Grove Music Online). A more exhaustive explanation was offered by the composer’s brother, Giulio Cesare Monteverdi, in the afterword to Claudio’s 1607 book titled Scherzi musicali a tre voci, stating that “music is the servant of the text”, that is, the primary objective is the expression of the text, to which all devices including rhythm, melody, and harmony should be subordinated, even with the use of dissonances if the text requires it. In earlier practice, dissonance use, among others, followed strict rules (for example, dissonant intervals such as sevenths or seconds were only allowed to appear as passing notes or as the result of a delay). Composers of the prima pratica (that is, “first practice”) include Johannes Ockeghem, Josquin des Prez, and Adrian Willaert, whereas those who followed the seconda pratica (“second practice”) comprise Cipriano de Rore, Carlo Gesualdo, Marc’Antonio Ingegneri, Luca Marenzio, Giaches de Wert, Luzzasco Luzzaschi, Peri, and Caccini (Lax, 1998).

This study is partially based on research for the author’s doctoral thesis (Duffek, 2018).

Vocal Genres of the Period

At the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, various vocal genres were present in Italy, including the villanella, aria, madrigal, motet, and the emerging opera. These are discussed in detail below.

Villanella

The term villanella means: country girl. It refers to songs written in the first half of the 16th century in Neapolitan dialect, which resembled country songs, had a “rustic” character, consisted of 3-4 voices, and were often composed in verses. It quickly became popular in Northern Italy in a more refined version, which was similar to the original primarily in its topic (e.g., pastoral life). The composition was rather simple and homophonic. In the 17th century, the term also referred to a composition for solo voice with basso continuo instrumental accompaniment. Such works often have an element of humour and irony (Cardamone, Grove Music Online).

Aria

Most people would think of a melodic piece within an opera when the term aria is mentioned. In the early 17th century, however, “aria” was used for a not entirely defined genre, which, during the century, came to form part of the emerging opera. Around 1600, the term generally referred to a standalone piece for solo voice, potentially with instrumental accompaniment, which was performed either separately or within a larger composition. Its role was significant in the evolution and emergence of the monodic style. The term is of Greek origin, signifying “air”. It was also used in instrumental music, especially in the 17th and 18th centuries, mostly in a stylistic or aesthetic sense to denote the performance style. Vocal arias are often composed in verses, which is the main distinction between them and monodic madrigals for solo voice (Westrup, Grove Music Online). However, some through-composed works were also called “aria”. In Caccini’s collection titled Le Nuove Musiche, the last 10 works are named “Aria”, all of which, save the first one, have a song structure. The underlying text is usually based on a love poem or, less frequently, a religious poem.

Madrigal

Musicologists trace back the origin of the word madrigal to the Latin matricale (mother tongue), in reference to the fact that madrigals were composed in the composer’s native language. The madrigal literature is mostly based on secular poems, especially about love or pastoral idylls. In a similar way to arias, a small subset of madrigals was also based on religious texts in Italian, which were called religious or spiritual madrigals, that is, “madrigali spirituali”. The most renowned works in the genre include Monteverdi’s collection titled Madrigali spirituali (1584) and Lagrime di San Pietro (Saint Peter's Tears) by Lassus (1594). The latter contains 20 madrigals as well as a motet in Latin as the last piece in the collection.

In Northern Italy in the first half of the 14th century, the madrigal was originally a poetic genre with two verses of two or three lines and a recurring verse of one or two lines, each seven or eleven syllables long. The rhyme scheme was usually: abba cc dd. Later on, these poems were often musicalised, until the term began to signify a separate musical genre. The performance of madrigals constituted a highly refined form of chamber music. Besides musicians of the court and the author of the text, members of noble or royal families could also participate in the performance.

The musical predecessor of the 16th-century madrigal was the frottola, which remained popular even after the emergence of the new genre. In the Trecento, the term madrigal referred to a polyphonic piece with two or three voices and frequent returns. In the early 16th century, the word madrigal meant a genre similar to frottola, which at the time had four voices, the highest of which had such a special significance that occasionally it was the only sung voice and the rest were sounded on instruments. By contrast, madrigals had at least three voices with more refined and polished words than frottolas. Sometimes mythological similes and metaphors were also included in the text. One voice was performed by one singer, potentially with additional instruments. A possible arrangement was to sing the upper voice and play the rest on instruments, just as with frottolas. Early madrigals were made up of verses, in a similar way to frottolas, which changed gradually to a linear composition, which was through-composed and not overly structured. Madrigals are characterised by polyphony, with more diverse homophonic inclusions than other verse-based vocal genres. There were three major stages in the 16th-century madrigal literature of Italy:

Early stage, from 1530. Notable composers: Philippe Verdelot, Constanzo Festa, Jacob Arcadelt, and early pieces by Adrian Willaert, Cipriano de Rore, and Domenico Giovane da Nola. The composition was characterised by linear (that is to say, polyphonic) thinking, while the range of voices expanded.

Classical stage, between 1550 and 1580. The number of voices increased, the polyphony grew more complex, and text illustration, that is, madrigalism, became common. It was in this period that the genre acquired the description of musica reservata (music composed for “experts” only). Notable composers: Willaert and his student, Cipriano de Rore, Andrea Gabrieli, Philippe de Monte, Jaches de Wert, Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, and Orlande de Lassus.

Late stage, between 1580 and 1620. Previous illustrative practices, including the imitation of nature and speech (“imitazione dalla natura, imitar le parole”) were further expanded by new and experimental elements (for example, the modern dissonances of Gesualdo da Venosa and Luca Marenzio). Notable composers: Gesualdo, Marenzio, and Claudio Monteverdi.

Although not every listed composer was born in Italy, they all served in Italian courts and used Italian to compose madrigals. In German-speaking regions, the Italian model was followed in madrigal composition. For example, Hans Leo Hassler was Andrea Gabrieli’s student in Venice, while Heinrich Schütz studied madrigals by Giovanni Gabrieli and Monteverdi. The madrigal became a popular genre also in 16th-century England, with notable composers such as William Byrd, Thomas Morley, Thomas Weelkes, or Orlando Gibbons.

“At the end of the century, an Italian fashion caught on there, affecting customs, clothing, language, every branch of art, and, needless to say, music” (Orselli, 1986, p.39)

The fashion had an influential book, namely Baldassare Castiglione’s (1478-1529) Il libro del Cortegiano (The Book of the Courtier, 1528), which was translated to English in 1561.

The most common poetic forms used in madrigals were the sonnet, canzone, ottava, the above-mentioned madrigal, or sections thereof. Poets in the 16th and 17th centuries often wrote their poems to be musicalised, especially those in the madrigal form. This poetic style was called poesia per musica (“poetry for music”). The mostly Latin-language literature of the Quattrocento was gradually replaced in Italy during the Cinquecento by literature in the national language, Italian. The origins of Italian-language poetry can be traced back to Francesco Petrarca (1304-1374) in the Trecento, hence the name of the 16th-century movement of Petrarchism. Cardinal Pietro Bembo (1470-1547), who himself wrote poems, had a great influence in the emergence of the movement. “He considered Petrarch as a role model not just linguistically and stylistically” but also in the sense of a role model who “reveals to people the way to true love and true suffering” (Madarász, 1994, p.128). Petrarch’s Song Book (Canzoniere or Le Rime) was admired and mirrored by many 16th-century poets. His sonnets often contain the paradox of hopeless longing and sweet romantic struggle; in other words, suffering and love, despite the contrast, do not exclude but complement each other in poetry. The target of his eternal love, Laura, is elevated to an insurmountable distance, is revered, and is treated almost like a goddess. This flaming and passionate yet longing and painfully sweet romantic suffering was attempted to be composed into a poem by numerous 16th-century poets, or at least those who considered themselves as such.

Based on Petrarch, the sonnet was a popular genre even among Petrarchists. The sonnet consists of two major sections, an ottava (eight-line section) and a sestina (six-line section), which then can be further divided into two quartinas (four-line stanzas) and two terzinas (three-line stanzas), respectively. The rhyme scheme is usually the following: abba abba cdc dcd.

The linguistic innovations Petrarch used to praise Laura, namely that certain words are homophones of or similar to her name, was a frequently used playful device among 16th-century poets (for example, l’aura – air/breeze, l’aurora – dawn, and lauro – laurel, or praise figuratively). Such motifs are also present in the multiple madrigal collections from the 1580s compiled in honour and praise of Laura Peperara and her external and internal qualities, who was a virtuoso singer in the renowned ensemble of Ferrara, the concerto delle donne (“women’s ensemble”), and was also Torquato Tasso’s muse (Materassi, 1999). The ensemble comprised noblewomen of exceptional training and virtuoso vocal technique, who also played, mostly plucking, instruments and accompanied themselves. They became treasured members of the court and were known and recognised throughout Italy. Their performances included exclusive private concerts hosted by Duke Alfonso II d’Este, where the Duke himself selected the attendees. The musical circle and corresponding events were called musica secreta (“secret music”) at the time (Newcomb, 1980). Tasso was not the only artist influenced by the “women’s ensemble”. Several compositions, including various madrigals by Marenzio, Wert, Lassus, de Monte, and Luzzaschi, were dedicated to the ladies in praise of their talent and beauty (Materassi, 1999). Caccini also attended their concerts, which contributed to his decision of establishing his own ensemble (Carter, Grove Music Online).

In the early 17th century, Giambattista Marino (or “Cavalier Marino”, 1569-1625), born in Naples, was another model to follow, who rivalled in popularity of his poetry and style both Petrarch and Petrarchist poets. He was the father of Marinism, the Italian Baroque literature style named after him. His poems were rather licentious and unchaste, and depicted bodily pleasures. Beauty and love were illustrated hedonistically. In his epic titled Adone (L’Adone, 1623), dedicated to Louis XIII of France, heroism is of secondary importance behind love. The epic poem contains many metaphors and allegories, but its lengthy descriptions were criticised by contemporaries, among other things. As opposed to this style, we find

“[…] the classicising Fulvio Testi (1593-1646) or the elegant Gabriello Chiabrera (1552-1638), who rejected the verbosity of Marinism, as well as tragedy writers of the time who presented elevated moral examples in their tragedies in opposition to the hedonism of Marinism” (Madarász, 1994, p.194)

Composers of the time also favoured canzonettas by Chiabrera. The canzonetta was a poem with short stanzas in the 16th to 18th centuries, with the emphasis on the last or penultimate syllable, resulting in a dance-like character (DeFord, Grove Music Online).

In discussing madrigals, it is crucial to acknowledge the above-mentioned Tasso (1544-1595) and Giovanni Battista Guarini (1538-1612). Certain passages in Tasso’s heroic poem titled La Gerusalemme liberata (The Liberated Jerusalem) as well as his other lyrical works such as the pastoral poem titled Aminta were often musicalised. Guarini often intended his compositions as “poesia per musica”. Not just the lyrical passages of his pastoral poem titled Il pastor fido (The Faithful Shepherd) but also his other works were frequently used as the foundation for composers’ pieces, mostly madrigals. His wife, Taddea Bendidio, and his daughter Anna were famous singers. The latter was a recognised member of the “women’s ensemble” of the Este family in Ferrata from the age of seventeen, where she was admired by the people in the court for her singing and lute performance (Wistreich, 2017).

As explained in the introduction, the illustration of the text was crucial for 16th-century composers. Musicalisation usually followed the structure of the poem. The end of each stanza was marked by a musical cadence. For example, in the case of sonnets, the transition between ottava and sestina was often illustrated by the composition of two separate but connected pieces (“prima parte” – “seconda parte”). The importance of painting words and textual content was underscored by highlighting decisive words in the music and associating an independent musical characteristic with certain words. Besides the madrigalist characteristics explained in the introduction, other musical devices were also used, such as recreating a dialogue between participants of a pastoral idyll by alternating different voices.

Claudio Monteverdi’s brother writes that “music is the servant of the text”. Pierluigi Petrobelli states the following in his book titled Poesia e Musica (1986): the text is “the matron of harmony” (“padrona dell’armonia”). This perspective influenced and formed the musical thinking of the period and resulted in its distinctively diverse musical toolbox, which allowed madrigalism and text illustration to influence madrigals of the Cinquecento and contributed to the emergence of the opera.

Opera

As explained in the introduction and in the chapter about madrigals, the antecedents of opera include dramas from Ancient Greece, the precise and highly visual expression of the text, and the consequent changes in the musical toolbox, all of which contributed to the emergence of the “musical drama”, not in the Wagnerian sense, or the opera.

Stage music and stories with acting and musical passages were present in Italian courts in various forms. One was the theatre play, which had evolved from the pastoral play and was usually performed during a ceremony in court. This was not a strictly musical performance as the production also featured other art forms such as literature or dance. Painters and sculptors also had a pivotal role in such performances. Besides adorning the stage, they were responsible for costumes and masks and even helped actors change during the premiere. Guarini’s Il pastor fido and Tasso’s Aminta were premiered in such events in Ferrara (Orselli, 1986).

Mystery plays, the dramatised portrayal of saints’ stories and legends, and processions, religious ceremonies commemorating feast days and similar celebrations, were also common. The trionfo, the procession of people sitting in a carriage or walking, evolved from feast day processions. Originally religious, such as the procession on the Feast of Corpus Christi, processions often became secular, such as carnivals. Mystery plays were understood throughout Europe because biblical stories and legends were widely known.

“[…] in all other respects the advantage was on the side of Italy. […] The majority, too, of the spectators – at least in the cities – understood the meaning of mythological figures, and could guess without much difficulty at the allegorical and historical, which were drawn from sources familiar to the mass of Italians” (Burckhardt, 1978, pp.252-253)

It is with reason that Burckhardt mentions this, since most pastoral plays and early operas were based on some mythological story.

In October 1600, a series of celebrations was organised in honour of the wedding between Maria de’ Medici and Henry IV of France. It was on this occasion when Eurydice, Peri’s pastoral tale based on the libretto by Ottavio Rinuccini (1562-1621), was premiered and the musical version of Il rapimento di Cefalo (“The Abduction of Cephalus”), a work by Chiabrera (who was also member of Corsi’s Camerata society in Florence) was commissioned, with music by Caccini, Stefano Venturi del Nibbio, Luca Bati, and Pietro Strozzi (Orselli et al., 1986). The mythological legend of Orpheus and Eurydice, Orfeo ed Euridice in Italian, was quite popular and inspired compositions, besides Peri, by Caccini (Euridice, 1602) and Monteverdi (L’Orfeo, 1607). Although the plot is fundamentally the same, the two former composers relied on Rinuccini’s text, while Monteverdi used the libretto written by Alessandro Striggio the Younger (1573-1630).

At that time, clearly separable arias and recitatives were not yet present, but their roots were perceptible. Monteverdi’s Orfeo contains virtually everything from the toolbox of the period: monodic style, tools of seconda pratica, alternation between solo and choir, duets, imitational composition, madrigalism, instrumental intermezzos, ritornellos, rhythmic curiosities, and sections in song form with varyingly altered returns.

In Rome, the genre of opera evolved differently, especially in its choice of topic. The most popular theatrical genres there were the Jesuit dramas (or plays), which appeared in Jesuit colleges in the mid-16th century mostly for educational purposes. Drama performances posed a sort of rhetorical exercise for students, helped them master the Latin language in a fluent and correct manner, and assisted the learning process with respect to classical dramas. Christian morals and integrity were incentivised through the stories and parables (for example, the introduction of saints’ and martyrs’ lives or significant events thereof). Besides cultural and moral education, performances also affected the efforts against Protestantism as well as the development of theatrical techniques (Forbes, 1977). Music was part of drama performances but little is known about its extent and style as only the points at which music was to be inserted were specified. It is not surprising that operas in Rome revolved around similar topics. Most operas and theatre pieces which were created and premiered in Rome between 1610 and 1630 were written for some special celebration, when sufficient financial resources were available for a large crew, including musicians and dancers, for diverse costumes, and for decorations. In Rome, the influence of clerical aristocracy resulted in allegorical and moralising operas. The plot often featured supernatural occurrences, such as miracles, apparitions, or heavenly interventions, as well as humorous elements (Forbes, 1977).

Motet

When thinking about 16th-century Renaissance motets, the first thing that comes to mind is the series of religious works in Latin with four, five, or six voices by Palestrina, Byrd, or Victoria. Church music in the Cinquecento was dominated by such polyphonic pieces with imitational structure, which were also common at the turn of the century. In the 17th and 18th centuries, however, the term motet began to refer to any composition based on religious, mostly biblical, texts and sometimes even to other pieces based on spiritually inspired poems, without regard to denomination. The division between genres faded: since “concerti”, “motetti”, and “concentus” denoted similar genres, they were often used interchangeably. In the first half of the 17th century, pieces of a new style under the name of motet were composed based on elements of the seconda pratica, the emerging opera, and the monodic style. Soloistic motets for one or two voices and basso continuo with long vocal embellishments (passaggios) became popular (Wolff, Grove Music Online). It was Lodovico Viadana who published one of the first collections of religious vocal works with basso continuo accompaniment in 1602, namely the Op.12 titled Concerti ecclesiastici (Mompellio, Grove Music Online). This ended the dominance of stile antico, that is to say, the Palestrinian tradition of church music, although the traditional style remained prominent in Rome and in Southern and Catholic regions of Europe (Roche and Dixon, Grove Music Online). 17th-century stile antico motets were not as strictly structured as those in Palestrina’s time and contained innovations such as chromatics or the concertante style (Dyer, Grove Music Online). In the context of vocal words, the latter refers to a multi-choir technique but is also used to describe a setting with multiple orchestras. Among the early proponents of the style, we find Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, who worked in Venice.

The new monodic style became popular in Italy, as evidenced by Monteverdi’s solo motets and the soloistic sections of Vespro. Gregor Aichinger 1607 book titled Cantiones ecclesiasticae, which reveals that the new Latin-language monodic style became popular and common outside Italy early on, is also worth mentioning. Aichinger lived, among others, in Rome and Venice between 1584 and 1601, when he had the opportunity to study Italian composers’ works (Hettrick, Grove Music Online).

As polyphonic, imitational works as well as musicalisations of the monodic style were both present simultaneously in the genre of madrigal in early-17th-century Italy, the same contrast characterised the genre of motet, although polyphonic motets did not feature madrigalist devices extensively.

The Musical Characteristics, Style, and Performance Practice of the Period

From the early 17th century, the use of basso continuo, the continuous bass accompaniment, became common and standard, and developed into a defining and fundamental property of Baroque music. In the early 17th century, it had few numberings, but later the notation expanded. It is important to study lute tablatures to gain knowledge of the style and to receive diverse inspiration for the execution of certain harmonies or passages.

The concertante style was also widespread, either in the form of multiple separate orchestras or by comparing and contrasting multiple instrument groups or voices within one orchestra or choir. It was common to alternate between solo and tutti parts, homophonic (often recitative) and polyphonic sections, and chord-based and linear composition. All of this of course occurred with the objective of expressive text illustration. It is worth listening to and exploring every movement in Monteverdi’s Vespro Della Beata Vergine, but even if we consider the Dixit Dominus movement, we can find almost all of the musical phenomena detailed above.

Ornamentation

Ornamentation was an integral element of 17th-century musical performance, which was often improvisational and left at the musician’s discretion and sense, within the stylistic framework. Classical musicians today encounter all, or at least several, styles and genres, from various periods. Consequently, it takes longer for performers or students who wish to be professional musicians to internalise the style of a period or genre, shaping in the process their own taste and performance, which can be employed in performance but do not go against the characteristics of the period or genre. In the early Baroque period, however, performers played “contemporary” music almost exclusively, which meant that their sense of style could develop sooner and the use of gestures and ornaments was unambiguous, that is, basically natural. Musicians in our time are used to scores which display every note to be played, making it difficult for them to rely on the sheet music to a lesser extent. It seems, however, that not all performers in the second half of the 16th century and in the early 17th century were experts in embellishment culture: there were ambiguities in performance practice and occasional over-ornamentation was also reported. The statement is further evidenced by treatises from the period which were written especially to explain the rules and practical execution of ornaments, or “passaggi” in the Italian terminology of the time. The original meaning of the term passaggio is “passage, transfer”, but in the context of music it refers to the passage which fills the gap between two notes. In the 16th century, the term denoted a virtuoso ornament or series of ornaments which were originally improvised and later prescribed by the composer in both vocal and instrumental music. Ornaments were used freely, not just in cadences. In vocal pieces the objective was usually madrigalism, that is to say, the illustrative expression or emphasis of a word.

The above-mentioned treatises (on the rules and practical execution of ornaments) include[1]: Giovanni Luca Conforti’s Breve et facile maniera d’essercitarsi… a far passaggi (1593), Giovanni Battista’s Bovicelli Regole, passaggi in musica (1594), Aurelio Virgiliano’s Il Dolcimelo (around 1600), Giulio Caccini’s Le Nuove Musiche (1601/2), or Francesco Rognoni’s Selva di varii passaggi (1620) (Carter, Grove Music Online). The first of two volumes of Rognoni’s book addresses proper vocal techniques, while the second describes adequate techniques on string and wind instruments (Lattes and Toffetti, Grove Music Online). His father, Riccardo Rognoni (Rognono), was also a musician, who published two collections of technical exercises in 1592 to help others master the vocal and instrumental performance of passaggios, that is, long and sometimes virtuoso ornaments, under the titles Passaggi per potersi essercitare (Venice, 1592) and Il vero modo di diminuire (Venice, 1592).

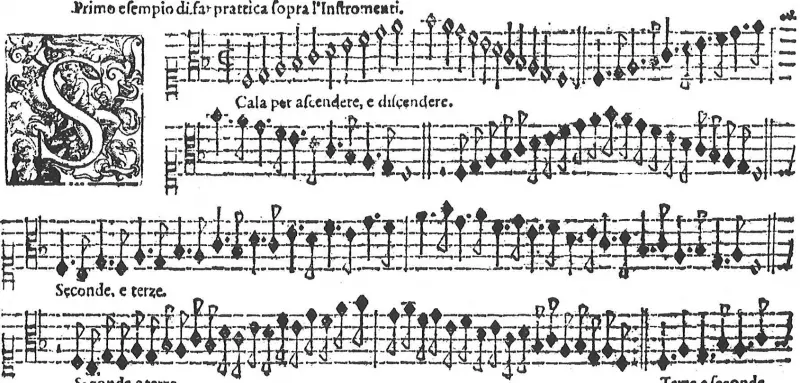

Excerpt 1: R. Rogniono: Passaggi per potersi essercitare, page 5 (fragment)

Scale sequences (C major or F major in this case) should be played first as individual notes, than with rhythm variations, followed by sequential repetitions. Excerpt 1 is taken from the very beginning of the book. Exercises towards the end of the collection require increasingly virtuoso techniques. Practising the exercises properly helped vocal and instrumental performers use their voice or instrument in a refined, light, and virtuoso manner.

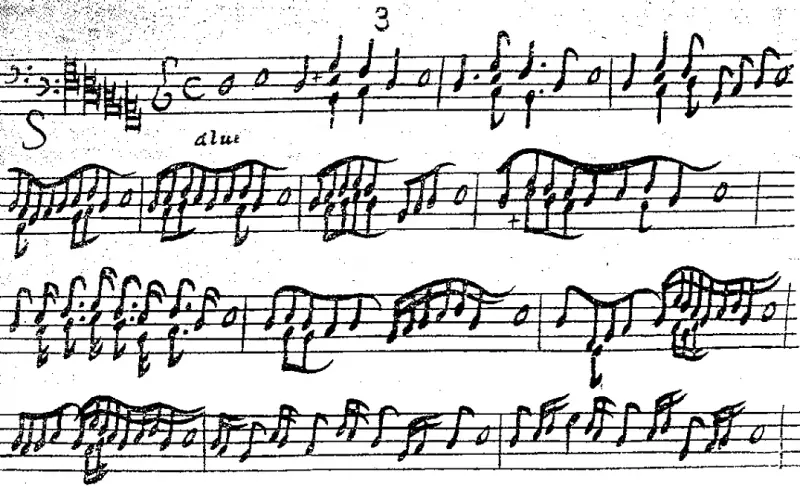

Besides its many exercises of vocal and instrumental technique, Conforti’s Breve et facile maniera d’essercitarsi… a far passaggi also contains instructions with respect to the ornamentation and diversification of simple intervals with small rhythmic values or melodic passages.

Excerpt 2: G. L. Conforti: Breve et facile maniera d’essercitarsi… a far passaggi, page 3

The included excerpts show that the exercises may be read and practised in any key. Here, suggestions in relation to ascending second steps are presented.

Bovicelli’s book titled Regole, passaggi in musica summarises the rules of proper ornamentation, as the title suggests.

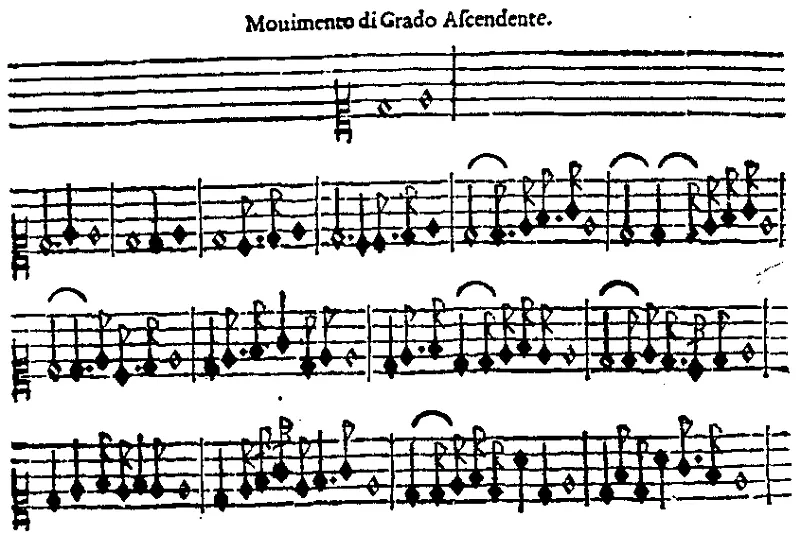

Excerpt 3a: G. B. Bovicelli: Regole, passaggi in musica, page 17 (fragment)

In the first row, the ascending D–E second step is displayed (“Mouimento di Grado Ascendente”), followed by the possibilities of its completion and embellishment in the next three rows of Excerpt 3a. Just as in Rognoni’s book, the virtuosity gradually increases.

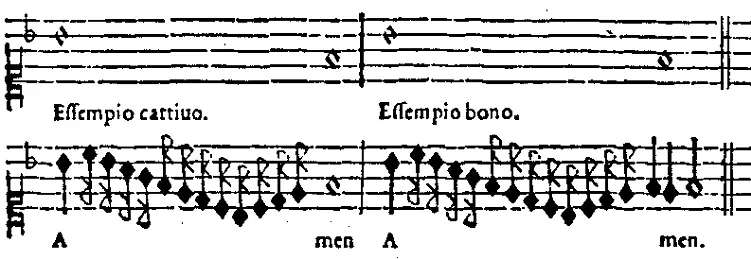

Besides suggesting proper versions, the book also presents certain incorrect forms of execution (“Esempio cattiuo”).

Excerpt 3b: G. B. Bovicelli: Regole, passaggi in musica, page 12 (fragment)

The figure shows the “bad example” first, followed by the “good example”.

Unlike Conforti’s book, Bovicelli presents more than just the embellished version of certain intervals. He displays motifs of multiple notes as well as the upper voice of entire compositions in the original and the suggested embellished versions by renowned composers including Palestrina, Cipriano de Rore, Tomás Luis de Victoria, and Claudio da Correggio.

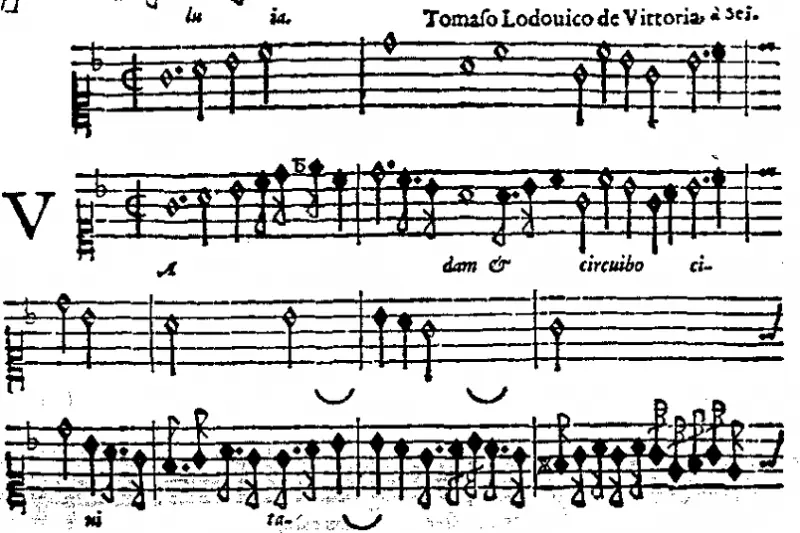

Excerpt 3c: G. B. Bovicelli: Regole, passaggi in musica, page 53 (fragment)

Excerpt 3c is taken from the upper (cantus) voice of the piece titled Vadam et circuibo by Victoria. Odd rows present the original score, while even rows show Bovicelli’s suggested ornamentation. It is difficult to imagine that the upper voice in such an embellished version should form part of a polyphonic motet with five, or occasionally two, additional voices; instead, the version was presumably performed in solo voice with basso continuo.

Nevertheless, execution according to the style might not have succeeded invariably in practice. In the preface of his book titled Le Nuove Musiche, Caccini condemns the practice of using ornaments, passaggios, without any regard to the textual message but with the sole intention of showing off virtuoso vocal techniques and receiving recognition for them. This way, performers were not “giving any other pleasure apart from that which the harmony was giving to hearing only, because it wasn’t possible to move the intellect without the understanding of the words” (Lax, 2003). In addition, he writes the following about singers’ style and performance:

“[…] now seeing many of them going around tattered and spoiled, badly making use of those long vocal girations, simple and double, even redoubled, one twisted up with another, when they [my songs] were invented by me in order to avoid that antiquated style of passaggi formerly the custom, but [which is] more appropriate for wind and string instruments than for voice. Likewise, I see used indiscriminately vocal crescendos and decrescendos, exclamations, trilli and gruppi and other such ornaments in the good style of singing. I have been required and also moved by my friends to have the said music printed and to show the reader in this first edition by means of this discourse the reasons that have induced me to such a manner of song for one voice alone, so that – music in recent times past not being accustomed to be of the complete charm that I feel resonates in my soul, as I know – I may be able in these writings to leave some vestige of it, and so that someone else may be able to reach that perfection, like a great flame from a small spark” (Lax, 2003, pp.471-472)

The way how singers used embellishments was just as important as their vocal training, which was also imperfect in some cases in Caccini’s assessment. According to descriptions from the second half of the 16th century and the first half of the 17th century, a good singer sings in low, middle, and high registers with equal tone and understandable diction, uses ornaments in the appropriate amount, and does so without difficulty (Donington, 1978).

Embellishment Techniques

All of the above-mentioned books address the embellishment techniques of the period, but the most comprehensive, precise, and detailed description with sheet music excerpts can be found in the preface of Caccini’s treatise. At the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, ornaments were used from both the traditional Renaissance music and the emerging Baroque music. In the last third of the 16th century, virtuoso vocal performance became increasingly common among musicians and vocal performers of noble courts. The concerto delle donne in Ferrara, which has been mentioned in relation to madrigals, consisted of such musicians.

As the quote from the preface of Le Nuove Musiche reveals, Caccini found at the time of publishing his work that many singers used passaggios to show off their own virtuosity and technical skills, instead of illustrating emotions and passions or expressing the text better. According to his assessment, ornaments should be used for accented and long syllables and in cadences because badly used ornamentations and passages are only good for “a kind of titillation to the ears” (Lax, 2003, p.475), but an interpretative performance is so much more.

In the preface of Le Nuove Musiche, the following elements of embellishment and performance practice are listed (I used the facsimile version of the first edition, which is available on the Internet, the Hungarian translation of the preface by Éva Lax (2003), which was published in the journal Magyar Zene, and the publication by H. Wiley Hitchcock (1970), which is based on the first edition from 1602):

Esclamazione (“exclamation”). Its meaning cannot be defined as precisely and clearly as that of other ornaments because it is a dynamical device in essence. A strong initiation is followed by a gradual decrescendo and then a crescendo for the next emphasised word or note (which can be gradual or sudden). Caccini presents two types, namely the esclamazione languida (“languid/longing exclamation”) and the esclamazione più viva (“lively exclamation”).

Excerpt 4a: G. Caccini: Le Nuove Musiche - A i lettori (“To the Reader”), page 4 (fragment)

Example for esclamazione

The first dotted note should be sung with a gradual decrescendo, then on the descent of the quarter note an increase is required and the whole note must be emphasised. The word “deh” (“oh”) should be initiated with spirit and diminished gradually. The esclamazione can be used in descending melodies, both for second steps and larger intervals (Kutnyánszky, 1994, p.14).

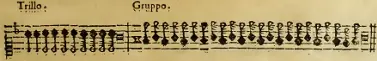

Trillo, also known as tremolo, and gruppo, also known as groppo (Carter, Grove Music Online):

Excerpt 4b: G. Caccini: Le Nuove Musiche - A i lettori (“To the Reader”), page 4 (fragment)

Example for trillo and gruppo

The first is the repetition of the note, which is often complemented with an accelerating rhythmic value, while the latter is the quick alternation between two notes a second apart (this is called a trill in the current terminology), which ends with a downwards step and another from the lower third to the closing note. Both ornaments occur in cadences, but the trillo is also employed to provide highlight or intensification: we can observe it, among other pieces, during the words “Sanctus” in the movement Duo Seraphim of Monteverdi’s Vespro for three tenors. The same movement also uses the ornament below.

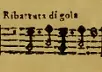

Ribattuta di gola (“glottal hit”):

Excerpt 4c: G. Caccini: Le Nuove Musiche - A i lettori (“To the Reader”), page 5 (fragment)

Excerpt 4c: G. Caccini: Le Nuove Musiche - A i lettori (“To the Reader”), page 5 (fragment)

Example for ribattuta di gola

This ornament was used for subsequent dotted notes on a way that dotted notes were initiated with glottal articulation. It is important to mention inegal (unequal) performance, which was often used for easier sound production (Donington, 1978). Caccini also suggests the modification of eight or sixteenth notes into dotted ones:

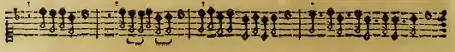

Excerpt 4d: G. Caccini: Le Nuove Musiche - A i lettori (“To the Reader”), page 5 (fragment)

Example for unequal performance

In the example above, odd bars contain the original version and even bars show the ornamented version for performers. (Eighth notes of the odd bars are transformed into Lombard rhythm in bar 2 and dotted notes in bar 4).

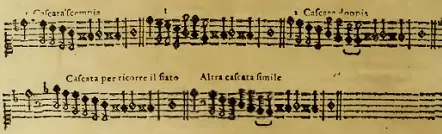

Cascata (“cascade/waterfall/fall”):

Excerpt 4e: G. Caccini: Le Nuove Musiche - A i lettori (“To the Reader”), page 5 (fragment)

Example for cascata

The cascade is the filling of an interval larger than a third with a descending scale sequence. Caccini does not mention its reverse, the tirata (“pull/drag”), which is the filling of a large upward interval with a scale sequence (Kutnyánszky, 1994).

It is worthwhile to compare the examples presented above with those in Conforti’s book, which also addresses possible ways of execution for the trillo, gruppo, or “groppo” in his phrasing, and cadences (“cadenza”), besides interval steps (ways to fill intervals from the second through the perfect fifth to the perfect octave). The differences and similarities between the examples of the two books are evident.

Excerpt 5: G. L. Conforti: Breve et facile maniera d’essercitarsi… a far passaggi, page 25

Excerpt 5 also features the “mezzo” (“half”), which denotes a shorter version of the trillo and groppo.

As it is evident from the preface of Le Nuove Musiche, Caccini found it important for singers to perform with some sort of noble effortlessness (“nobile sprezzatura”). This means that even difficult passages and improvised embellishments should be performed with ease. The concept also allows rhythmic freedom and flexibility corresponding to and articulating the meaning of the text (Lax, 2003). In essence, the most splendid performance can be achieved only if the performer does not struggle but sings instead with effortlessness and ease, bearing in mind that the performer’s potential technical difficulty is not the business of the audience. A performance is not brilliant because the performer tackles the piece or the difficulties but because these are overcome in a way which seems effortless. This should also be considered by performers today, regardless of genre or style.

“[…] the quick transition from the strict adherence to monodic singing to more structured forms with belcanto ornamentation or to the closed form of the aria, alongside the increasingly clear emergence of tonality in the modern sense due to the use of the accompanying harpsichord, shows that the birth of the musical drama opened a field for music which characterised the Baroque period but was the last act of the dying classicising culture”. (Orselli et al., 1986, p.11)

References

- Burckhardt, Jacob (1978): A reneszánsz Itáliában [The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy]. (Hungarian translation: Elek Artúr) Képzőművészeti Alap Kiadóvállalata, Budapest.

- Donington, Robert (1978): A barokk zene előadásmódja [A Performer’s Guide to Baroque Music]. (Hungarian translation: Karasszon Dezső) Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Duffek Ildikó (2018): Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger Arie és Motetti Passeggiati kötetei (1612) [Arie and Motetti Passeggiati Volumes of Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger (1612)]. DLA dissertation. Liszt Ferenc Zeneművészeti Egyetem, Budapest.

- Fabbri, Paolo (2007): „Orfeo. 1607.” (Transl. Lax Éva) Muzsika, 50/2. (February) 11-16.

- Forbes, James (1977): The Nonliturgical Vocal Music of Johannes Hieronymus Kapsberger (1580-1651). PhD dissertation. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. (Microfilm).

- Kutnyánszky Csaba (1994): Vokális ornamentika Claudio Monteverdi műveiben [Vocal Ornamentation in the Works of Claudio Monteverdi]. Thesis. Manuscript. Liszt Ferenc Zeneművészeti Egyetem, Budapest.

- Lax Éva (1998): Claudio Monteverdi. Levelek. Elméleti írások [Claudio Monteverdi. Letters. Theoretical Papers]. Kávé Kiadó, Budapest.

- Lax Éva (2003): Giulio Caccini: Le Nuove Musiche – Az olvasóhoz [To the Reader]. Magyar Zene, 41/4. (November) 469-486.

- Madarász Imre (1994): Az olasz irodalom története [A History of Italian Literature]. Nemzeti Tankönyvkiadó, Budapest.

- Materassi, Marco (1999): Il Primo Lauro. Madrigali in onore di Laura Peperara. Ms. 220 dell’Accademia Filarmonica di Verona [1580]. Ass. Mus. „Ensemble 900”, Treviso.

- Newcomb, Anthony (1980): The Madrigal at Ferrara. 1579-1597. Vol. I. Princeton University Press, New Jersey.

- Puskás István (1999): Palotaforradalom [Palace Revolution]. In: Madarász Imre (ed.) Italianistica Debreceniensis VI. Kossuth Egyetemi Kiadó, Debrecen. 35-36.

- Palisca, Claude V. (1976): Barokk zene [Baroque Music]. (Hungarian translation: Hézser Zoltán) Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Orselli, Cesare–Rescigno, Eduardo–Garavaglia, Renato–Tedeschi, Rubens–Lise, Giorgio–Celletti, Rodolfo (1986): Az opera születése [The Birth of Opera]. (Hungarian translation: Jászay Magda) Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Orselli, Cesare (1986): A madrigál és a velencei iskola [The Madrigal and the Venetian School]. (Hungarian translation: Jászay Magda) Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Watkins, Glenn (1980): Gesualdo. Élete és művei [Gesualdo. The Man and His Music]. (Hungarian translation: Szilágyi Tibor) Gondolat Kiadó, Budapest.

- Wistreich, Richard (2017): ‘Inclosed in this tabernacle of flesh’: Body, Soul, and the Singing Voice. Journal of the Northern Renaissance, 8 (Spring) 1-27.

Websites

- Cardamone, Donna: Villanella. Grove Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/29379?q=villanella&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit - Carter, Stewart A.: Ornaments. 4. Italy, 1600-50. Grove Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/49928pg4#F921797 - Carter, Tim: Giulio Romolo Caccini. 1. Life. Grove Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/40146pg1?q=concerto+delle+donne&search=quick&pos=7&_start=1#firsthit - DeFord, Ruth I.: Canzonetta. Grove Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/04808?q=canzonetta&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit - Dyer, Joseph: Roman Catholic church music. III. The 17th century. 3. ‘Stile antico’. Grove Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/46758?q=ottavio+durante%27s+arie+devote%2C+1608&search=quick&pos=2&_start=1#firsthit - Hettrick, William E.: Aichinger, Gregor. 1. Life. Grove Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/00345?q=gregor+aichinger&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit - Lattes, Sergio–Toffetti, Marina: Rognoni: (3) Francesco Rognoni Taeggio. Grove Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/23686pg3?q=Francesco+rognoni&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit - Mompellio, Federico: Viadana (Grossi da Viadana), Lodovico. 2. Works. Grove Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/29278?q=viadana&search=quick&pos=3&_start=1#firsthit - Palisca, Claude V.: Prima pratica. Grove Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/22350 - Roche, Jerome –Dixon, Graham: Motet. III: Baroque. 2. Italy. (i) To 1650. Grove Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/40086pg3?q=motet+baroque&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit - Westrup, Jack: Aria. Grove Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/43315?q=aria&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit - Wolff, Christoph: „Motet. III: Baroque. 1. General.” Grove Music Online.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/40086pg3?q=motet+baroque&search=quick&pos=1&_start=1#firsthit

Scores

- Bovicelli, Giovanni Battista (1594): Regole, passaggi in musica. Facsimile.

http://hz.imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/7/71/IMSLP408006-PMLP198697-bovicelli.pdf - Caccini, Giulio (1602): Le Nuove Musiche (Firenze). Facsimile.

http://ks.imslp.net/files/imglnks/usimg/b/bb/IMSLP286641-PMLP116645-lenvovemvsichedi00cacc.pdf - Caccini, Giulio (1970): Le Nuove Musiche. Modern transcription. Publisher: H. Wiley Hitchcock: Recent Researches in The Music of The Baroque Era IX. A-R Editions, Inc., Madison.

- Conforti, Giovanni Luca (1593): Breve et facile maniera d’essercitarsi […] a far passaggi. (Rome) Facsimile.

http://petrucci.mus.auth.gr/imglnks/usimg/7/7e/IMSLP95119-PMLP195826-Conforti.pdf - Rogniono, Richardo (1592): Passaggi per potersi essercitare. (Venice) Facsimile.

http://imslp.nl/imglnks/usimg/a/af/IMSLP292278-PMLP474374-passaggi_etc_ricardo_ognoni_parte1.pdf - Rogniono, Richardo (1592): Il vero modo di diminuire. (Venice) Facsimile.

http://petrucci.mus.auth.gr/imglnks/usimg/7/75/IMSLP292311-PMLP474374-passaggi_etc_ricardo_ognoni_parte2.pdf

[1] The facsimile sheet music excerpts of this study can be found on the internet. The list is in the References section.