Author: Tamás Ittzés

DOI: 10.5434/9789634902263/16

Abstract

This study details an approach which, in a certain respect, simplifies violin playing and teaching in the extreme. Creating a sound is based on a very simple rule: the sound = release. Release is preceded by tension, which is released with the sounding of the note. This is true on every level, in every direction. This general rule (or view) helps to make violin playing, the sounds created relaxed, natural and beautiful. The study shows step by step, how the necessary active tension comes into being and then how it is released, how and in what forms performers can use gravity. The main elements of this process are the posture of the body and the instrument, the movements of the arms and the joints (shoulder/armpit/upper arm. elbow/lower arm, wrist/back of the hand/palm and fingers) in their natural direction, the positions of the left hand, touch and vibrato, the relationship of the bow to the string, the use of bowing positions and right bow division, and strokes. Without the appropriate teaching of these no mechanism can be established and because of these deficiencies many a talent has been lost unable to even approach their own boundaries and unable to ever become a professional player.

Keywords: sound production, release, natural mechanism, freedom, gravitation, violin

Introduction

There is nothing new in this study, at least in the sense that everything I use when treating violin playing as a system and what I share with the reader is really obvious or even commonplace. Nevertheless, during my 27-year career in teaching I have mostly met negative examples and a lot of false beliefs and misunderstandings which, in my experience, are present in everyday teaching. The artistic and even the mechanical part of music are obviously areas where several truths may exist side by side and what is more, it is impossible to write about this field lucidly and without being misconstrued. I feel I still have to give it a try.

The primary aim of this study is to pass on an approach which, in a certain respect, simplifies violin playing and teaching to the extreme. Since of all instruments the violin is probably the most complex (and therefore most difficult to play) considering its instrumental technique, and instrumental and playing mechanism, it is vital to have precepts to hold onto both for the student and the teacher which can help them in any difficult situation and serve as guidance, or starting point to solving a given problem.

My axiom is an obvious commonplace, a very simple rule: the sound = release. For some reason this basic law valid for all instruments is generally missing from practical violin teaching, and violin tutors also disregard this fundamental principle (together with some others) and even work against it in some cases. Release is preceded by tension which is released with the sounding of the note. This is true to every degree – in every manifestation. This is a general rule (or view), which helps to make violin playing, the sound created relaxed, natural and beautiful.

A blatant example of how release from tension is neglected is the teaching of building of sound. Although the production of sound has aspects which cannot be described or learned, we often disregard the basics, the mechanism that can be learned. Perhaps the most wide-spread among the general mistakes of violin teaching is that instead of the most natural movements possible most teachers try to teach details of precision mechanisms as ‛sound production’, which are often not adequate by themselves, but even when they are, should only be taught after the basic movements are in place. By ‛basic movements’ I mean when each part of the body, each joint, moves in its natural direction. Although this seems obvious, it does not work with at least 90 per cent of violinists or it works inadequately. It is as if we tried to teach Usain Bolt precise movements resulting in gains of split seconds before he had learnt how to walk. 90% of violinists cannot ‛walk’, but we teach them to run and expect them to practise fine movements with the help of which they can ‟gain tenths of seconds” when they cannot even walk.

This study is an impossible venture because, owing to the complexity of violin playing, it is preposterous to cram everything into one paper and the attached e-learning. material. In addition, to stay with the previous metaphor, although the basic topic is ‛correct walking’, because of its complexity, we cannot discuss the problem in general; we have to separate the parts of the body and the movements used in violin playing. At the same time, I will try to place these mechanisms into a holistic context and always point out the principle of sound = release. To be pragmatic, I will show you, step by step, how the necessary active tension comes into being and then releases, how and in what ways we can use gravitation. The main elements of these are the posture of the body and the instrument, the movements of the arms and the joints (shoulder/armpit/upper arm, elbow/lower arm, wrist/back of the hand/palm and the fingers) in their natural direction, the positions of the left hand, touch and vibrato, the relationship of the bow to the string, the use of the right section of the bow. Without the appropriate teaching of these no mechanism can be established and because of these deficiencies many talents have been lost who cannot even approach their own boundaries and will suffer through life as disappointed violinists or, in the better case, will not even become professional players. Do not be deceived by the unusual, irregular technique of the violinists celebrated as great artists: they are the few, the tip of the iceberg, in whose case the urge for musical expression was so strong that they could call forth the result they wanted to achieve with their instrument in spite of a wrong mechanism. A thousandfold more were ruined as violinists with a similar desire for expression and similar mechanisms but perhaps with not such advantageous physical properties. As teachers we cannot make the mistake of being blinded by the talent of a musically intuitive child and allow them to develop their expressive abilities with the wrong mechanism since, sooner or later, it will lead them into a blind alley.

Do Not Do Anything!

The most difficult task is the most important: do not do anything, just let gravitation and natural physical functions work. The mechanism does not work otherwise. In order seemingly not to do anything, we have to be conscious of a great number of things and have to position each of our body parts and joints in a way that when sound is produced, they could be released in the most natural way possible. What are the things we have to be aware of?

- Each part of the body (primarily the parts of the arms and the hands) has to move in in own natural direction: the simplest way to check this is to observe in what direction and angle our arms (shoulder, upper arm, lower arm, hand) move in relation to one another when we walk with our arms hanging down. This will be the most comfortable, natural position with raised arms as well. Violinists can very often be seen holding the instrument (and their left arm) overly outwards or inwards. Another fault is when their right upper arm is held very high or very low when playing, which prevents the lower arm from moving into its natural direction. Therefore they either twist their position even more, making false compromises, or produce ugly sounds when playing at certain sections of the bow.

- The bow has to be allowed to work in its own way, utilising its own flexibility and lightness, as we should not interfere with the free movement of our arms and hands. The secret is good preparation. I have to raise the bow into a position from where it will fall on the string with the appropriate weight, speed and angle. This is valid for tones started from the string as well.

An important remark: correct standing position is, of course, essential (in a given case sitting, which we will return to later) but its details exceed the boundaries of this study. However, we have to remark that we have to stand on our two feet or, if we stand on one foot, we have to place the weight on the left foot. When weight is placed on the right foot (especially in counterpoise), the spatial sensation of the right side and the right arm is extremely limited and the bow hand will be unable to move with the proper freedom.

Basic Anatomical Information

Before detailing violin mechanism, it is important to clarify a few basic notions which violinists, for lack of anatomical studies, have no or very little information about and even if they do, they ignore them when playing.

The body is an extremely complex construction, each component of which is related to the others. Any disruption of the balance of the body (in the literal and figurative sense) will result in negative, in cases damaging or pathological, deformations. Therefore it is especially important to hold on to the natural position of the bones, joints, muscles and tendons used when playing the violin and, after they have been used, to restore the natural position in order not to make violin playing physically demanding and to retain balance.

Atlas, sternocleidomastoid muscle: in respect of any motion the vertical balance and proper division of weight are fundamental. The highest point responsible for correct balance is the first cervical vertebra (vertebra cervicalis prima). The head rests on the atlas (its weight can amount to 10 kilos in a physically big person), and when we nod, we drop our heads from there, from the back, (e.g. onto the chinrest), not from up front where the jaw and the neck meet or from the Adam’s apple as can often be seen with certain violinists. We must be aware that in a stiff, unnatural head position our muscles have to bear 5 to 10 kilograms of weight continuously, mostly lopsided. The weight of the violin with its accessories weighs over one kilogram, so for the ‘safe’ holding of the instrument it is not worth overloading our muscles with the weight of our head.

Further points stabilizing the body are the arms, the groin, the hip joints (a focal area), the knee joint, and the ankle joint. (Johnson, 2009, p. 36.) These points of balance have to be placed alongside a vertical line one above or under the other. It is useful to realise that the muscles and tendons which reach the shoulders, the shoulder-blade and the arms originate from the nape so that any tension that occurs during violin playing is connected to the neck or starts out from it (in the case of stiffness of head position).

Free shoulders: though it sounds strange, our arms hardly connect to our frame, they have no fixed connection either to the spine or with the ribs. It is only the collarbone which lies in the pit of the breastbone, and thus is capable of rotating movements, to which the nape is connected in the shoulder joint. The nape lies on the ribs at the back of the body but is not in direct contact with them because of the muscles in between. Our shoulders (and thus our arms, too) constitute an independent, suspended system supported primarily by the muscles. We would not be able to rotate the arm only from the shoulder joint. In order to completely free the movement (to achieve the sense of complete freedom) we need to utilise the movement of the collarbone and the nape. (So the violinist must not press their shoulders and play only from their arms because the space of movement will then be narrowed down. This naturally does not mean that playing should start out from the shoulders.)

Elbow joint or how pronation and supination work? The rotation movement of the arm (pronation is turning inside, supination is outside) is made possible by the flexibility of two bones of the lower arm starting from the ball-and-socket joint of the elbow: the (ulna) and the spoke-bone (radius). It is interesting to note that the two bones cross each other when the arm is in its base, hanging position and they are parallel when the palm is turned outwards (supinated). What is important here for violinists is that the radius turns here around the ulna, that is with palm turned outward (in a supinated state) the two bones are situated in parallel next to each other, while at the turning of the palm downwards (in case of pronation) the centre of rotation is the ulna, next to the little finger. A typical mistake of those working with their hands (especially artists) that when making a rotating movement the centre is the side near the index finger or thumb instead of the little finger. So they turn the side near the little finger upwards (violinists raise their elbow) thus generating superfluous tension. (Johnson, 2009, p. 189.) Or take the case when on the left side we rotate the left hand (arm) around the first (index) finger when the fourth (little) finger comes after the first instead of focusing on the little finger with the help of the elbow. Thus the first finger would be in a relatively higher position over the string (or it would stretch over one of the lower strings), These incorrect motions when repeated many times (when we do not take into consideration natural movements and practise the mechanically wrong motion) will directly result in the permanent tiredness, stiffness of the left hand, and later tendonitis.

There are 27 bones in the hand. The human skeleton comprises 206–208 (according to another definition 217–219) bones. (The difference stems from the different accounting of bones which are grown together. The lower figure does not take into consideration the 3–3 sesamoid bones in the hand. (Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_bones_of_the_human_skeleton#Arm) A disproportionate number of these, 27 bones, (if we include the sesamoid bones built into the tendons, the figure goes up to 30) are on one hand, so more than a quarter of all the bones in the body can be found in one hand. Making violinists aware of this may help them achieve to make a great deal more refined movements from their fingers which would anyway be necessary in certain cases. But, as stated in the previous paragraph, rotating motion has to start from the elbow joint. This is valid for many instances from the raising of weight on the bow to the string change in the left arm and its positioning. So we can place the hand together with the arm in a way that the fingers are in the place where they should comfortably be. The wrist is only capable of making a seesaw waving motion and a minimal lateral movement. The fingers, and especially the thumb, are capable of making a rotating motion following the surface of a cone starting from the very base of the finger, but we can only use this in a limited way in the intonation of the left hand and the bowing position of the right hand.

And finally: the most natural position of the hand is the half-sphere, clasping the way a baby and even an embryo is holding its hand. Why would we want to ignore and alter this natural position in the case of violin playing which requires the most complex movements?

Figure 1: The Hand of Hope (Michael Clancy, 1999)

(Sourse: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samuel_Armas)

The above photo was taken during the operation of a 21-week embryo with spina bifida (the baby was healthy at birth and there was no need for further operations). Reports are contradictory concerning whether the embryo was awake or anaesthetized when the photo was taken, but from our point of view it does not matter. It can clearly be seen that this is the most natural position for the hand and the fingers.

The Creation of Sound, Sound Production

The simplest way to study sound production is on an open string. And it is the easiest to start with plucking because playing the violin with the bow is nothing else but plucking with the bow. The way our finger gets caught in the string is the same as when the bow gets caught in it, creating tension between the plucking ‛tool’ (finger or bow) and the string. And as the finger is lifted up from the string, so is the bow. Furthermore, the sensation in the arm is also the same. Of course, it matters how we pluck, in what angle, how close to the fingerboard, or perhaps far away from the end, how soft our fingerpad is, how large the surface is, which finger we use, what our speed of plucking is, whether we start from the string or the air catching the string with the bottom of a ∪ line. We have to remark that the arch or the ∪ line changes with the dynamics and the speed, and it is rather similar to a tick (✔). It is the same sensation from the point of division of weight and speed as when we tick something on paper. And, of course, each string has its own (imaginary) surface, and the given falling angle and the direction of release have to be decided accordingly. By (falling) angle I mean the degree in which the bow approaches the string compared to the string surface which is zero in degree. The greater the angle is, the bigger the sound will be as it hits the string with more weight. However, it cannot reach 90 degrees as then it just falls into the string and it is stuck there.

The same procedure occurs on the left but in a smaller range, since there the fingers are perhaps in a more direct contact with the centre of the creation of the sound through the string (with the springing point of the meeting of the string and the bow), and the movement of the arm is also more limited. This does not mean that there is no need for arm movement, because the arm is a great help (try this by sensing how the swinging of the left arm outwards releases the right arm and it starts bowing by releasing the tension reached at the lowest point of the sinking).

The next example may help in understanding the sensation of the right hand at the start of a note: the physical sensation of the start of a note is the same as when we utter the syllable pah. The p consonant is mute in itself, so when we produce it, tension is created between our lips which only becomes a sound when we utter the ah vowel. The starting of a sound is the same as the sudden change from the consonant to the vowel, an opening, a release, where the change itself is always fast, and the shortness or length of the sound will be defined by the speed of the vowel. The same applies to the relationship of the bow and the string.

All things considered, we can summarise the mechanism of sound production in the following: I sink into the string and because of this weight (and not pressure!) tension arises between the bow and the string (on the left hand between the string/fingerboard and the fingerpad, then, when with my sinking I reached the lowest point, I push upwards, so tension is released at both points of contact and resonance starts depending on the speed of release. This is all. If there is no weight, there is no natural tension, if there is no tension, there is nothing to be released, if there is no release, there is no resonance, so there is no sound.

How Can Motions Be Released During Continuous Playing?

The justifiable question arises how the release produced relatively easily in the case of a short, speedy swinging bow can remain present in our playing when we play continuously (and/or with slower bow-speed). The solution is preparation. Again, I did not say anything new here, either, but still, I have rarely seen violin playing where EVERYTHING is prepared. In preparation the most important factor is that the next motion take place from the previous one, the preceding weight. This weight, to make matters simple and easy to understand, should now fall on the previous note (with swift passages a change of bow or position and its preparation should start eight notes earlier if that is where the preceding metric weight falls). So. if we play two accented minims with the whole bow, we have to prepare the placing and direction of the bow for the following note in the moment of release. To check the correct position of the bow, the hand, the lower arm, the elbow, the upper arm and the shoulder, we have to examine the optimal position for the starting of the next note, that is, at the lowest point – at the point we start springing upwards. Starting out from the optimal position of the two notes at the point of departure we may be able to join them in a way that we use the impetus of the start of the first note (that is its release and swing) to prepare the second note while we are continually in motion. It is important to start the preparation for the movement of the next note from the previous weight, that is from the previous release (in this case, the preceding note), otherwise, if we start in a different direction, we may only interfere with an effort into the natural movement of our body parts and this intervening change will be noticeable in the sound.

The key of maintaining release continuously is the same on the left side, but while the fingers remain more or less unchanged during bowing, the fingers of the left hand are in continuous motion. Preparation in the left hand depends on the touch which we will detail later, and the position which makes correct touch possible. It is very important to emphasise that in violin playing everything is rhythmic, or we could say, metric, and each change occurs on metric beats.

Let us take a simple example to illustrate this:

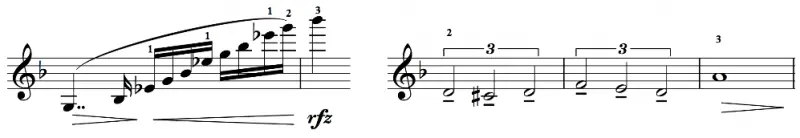

Figure 2: Preparation in the left hand. Written and actually played versions.

The small notes indicate the touched but not played notes.

The fourth finger, adequately prepared and brought into a comfortable position with the help of the elbow will sink into the string while all our fingers become rounded in their natural, hanging position, not excluding the situation when they reach over to lower strings, but in all cases near the strings.

Our fourth finger becomes lighter after the springing point (it is actually an imaginary surface) has been reached, this is when the A note of the example begins on the D-string. With the impulse of this relief the arm and the hand will roll towards the A-string (the elbow swings back a little to the left in order to position the first finger which, in the meanwhile, reaches backwards). The last thumb knuckle moves a little higher as well because of the rotating motion around the neck. It is important that the reaching back (or rather, swinging back) of the first finger will take place as a result of the release of the fourth finger, which is actually the production of the sound. If all the motions are carried out in proper rhythm and metre, the first finger will reach the A-string at the dividing point (since it is a minim, on the second crotchet dividing it) and will gradually sink into it while the fourth finger still plays the A note. The first finger, reaching the lower springing surface at the next beat, is released so there is a complete shift to the A-string. Our fourth finger leaves the D-string and, together with the other, non-playing fingers, takes its natural position on the half-spherical surface of the hand.

This seems very exhaustive when written down but we are talking about basically one movement, one series of motions which start from the first note (including the preceding sinking and springing up from it) but from there all the successive motions will use the energy of the previous one.

Preparation must take place in the right arm as well. When we start from the string and in case of down-bow, before the A is sounded on the D-string, the whole arm begins to sink, thus increasing tension between the bow and the string. Then, when it has reached the springing point, together with the release upwards (the sounding of the note), the upper arm continues sinking and so it prepares the change to the A-string. Meanwhile, while playing at the nut, even the upper arm starts moving slightly to the right, but with a slow stroke this does not mean pulling, only releasing to the right. The lower arm will be slightly raised corresponding to the release of the first note. From there at the crotchet division value (as the first finger of the left hand has reached the A-string) it ‛plunges down’ towards the A-string like a swing which has reached its highest point at the division value and, after a momentary stop, it swings back in the other direction. Therefore, owing to the proper metric preparation of the arm, the bow will tip over to the A-string exactly in the middle of the bar. If we play the same with a sustained forte or with crescendo and not letting the notes lighten up, then it is not our lower arm that will be released upwards after sounding the first note, but the releasing motion will be apparent in very small joints, perhaps only in the fingers. Nevertheless, it has to be present, at least as a sensation.

Of course, the situation is the same on both sides when a step is taken in the opposite direction (from the low first finger on the A-string to the fourth finger on the D-string). Only the left elbow must be even more active and the fourth finger will have to be prepared even better than the first finger on the right in the above example.

Positure and Holding the Instrument

Be Constantly in Motion

Free and effortless violin playing is in constant motion in order to u(tili)se the parts of our body needed for playing the instrument and being able to make them work. We will not feel safe if we make the instrument rigid and motionless. The instrument, the bow and all the components of the body we work with must be in constant motion – just as our music is. The level and intensity of motion, of course, changes all the time (mostly corresponding to the musical motions.)

How to Position the Instrument?

The violinist has to stand as one normally does: straight, with the head looking forward. This is the most stable position, the safest to move about with our arms, and our hands and fingers will be the most balanced in this position. We do not have to lean our head to the left, neither bend (and, what is even worse, flex) it to the chin-rest. (In this study it is not possible to describe the appropriate chin-rest and shoulder-rest in detail). The correct angle of the violin to our body is very important. The best method to find this correct, natural position is to see how our arms hang next to our body in a roughly 45-degree angle, with our palms turned towards our thighs. When we lift our left arm to a horizontal position (that is roughly shoulder-height), we will easily feel that, moving the arm to the right, tension will heighten at the back of the shoulder, and if we move it to the left, the front part will become tense. The arm is held the easiest somewhere in the middle (moving to the front, approximately 45 degrees left of the body). If we turn our palm upwards and let our elbow down, allowing our left arm to take the position we use for playing the violin, we will find this angle the most comfortable. For working naturally, this is where we have to place our arm and the violin. Any motion with the left arm, including the changing of strings and positions will be most comfortable in this way. And we can easily adapt this to the instrument with the bow and our right arm since we do not have to adjust it. (Note: it is important that when we lift the arm we should not feel a lifting up but feel that we have placed the full weight of our arm or elbow on an imaginary shelf, placed higher, so that our muscles are at rest even in this raised position.)

If we hold the instrument too far outwards (to the left) we either saw the air, or we pull to bring our right arm to the left so that the bow can move parallel with the bridge, and then our shoulder comes forward and the muscles at the back become tense. In case of an instrument held too far inward (to the right), the case is the opposite: we have to pull our shoulder back or let our elbow down so that the bow can be correctly placed on the string and then we can only achieve a good sound in the middle. We have to compensate on other parts of the bow while worsening the posture or making the harmonic motion of the structure of the lower arm – upper arm hand and the joints (shoulder – elbow – wrist – fingers) even more difficult.

Because of the above I find the use of the hard shoulder-rest especially damaging since it fixes the shoulder and the upper arm and forces the violin into a wrong angle and stuck in one place unable to move, and makes it difficult, or even impossible, to change strings with the right arm and elbow, which is a primary condition of correct intonation. The shoulder-rest only works when one is fully aware of the correct motions and is able to use it without constantly pressing it to the shoulder and the chin.

Why Do We Lift Up the Violin?

Probably every teacher has given this instruction: “Lift up the violin’. Reasons, however, rarely reach the pupils, although there are four of them:

- There is not enough room for moving the arm, especially the upper arm, if the instrument is hanging down. This is always wrong, but may be fatal at position-shifting, especially in higher positions.

- The bow is easier to manipulate on a horizontal string since the string will hold the bow. Whereas if the instrument is hanging down, we have to use some of the energy of the fingers of our right arm to hold the bow on the string and not let it slide down on the fingerboard. In addition, especially with a springing bow (spiccato, saltato, ricochet) the stroke becomes difficult to control since the weight does not work in the right direction. It is important to make students aware that, in order to reach a horizontal string position, we need to hold the instrument a little higher because of the angle between the body of the instrument and the string.

- The low tones of the violin resonate mainly on the back of the instrument. A raised violin will transmit more low frequencies to the listener than a dangling instrument. so the tone will be more resonant and rich in overtones.

- And, finally, perhaps the most important: to achieve a good tone, to take the weight off the right side, we need a base supported from underneath with the left arm. I have the sensation of the stroke in a majority of cases on the left side. A technique, especially useful when starting a note, is not to start with an energetic stroke on the right but rather using the left side to release a sluggish bow-weight dominated mostly by gravitation. This coincides with the curved, slightly upward movement of the left side to the left which is just one motion of the arm, while the weight of the bow (the thickness of the sound) is felt on the left by the arm, the palm and the fingers, adding a heightened activity to all the parts of the body and muscles taking part in the movement.

I often use the phrase ‟lift the scroll” because the intention to lift the violin usually results with our students in raising the whole of the left side including the shoulder. It is, however, only the scroll that has to be raised (that is the hand at the neck) and our shoulder should remain lower.

How to Play from the Music?

If we play from the music we have to stand in a way not to change the optimal position of holding the violin but to also see the music without an obstacle. I do not suggest a perpendicular placing of the violin relative to the music-stand which is the generally accepted solution. In this position the violinist has to turn their head to the left trying to read the music over the scroll. Either the scroll or the left hand will disturb the picture and this results in a hanging violin, and a twisted position of the body with stiffening limbs. It is much easier to stand opposite the music-stand with the violin held in a 45-degree angle to the left, as described above. Then the music is only occasionally covered slightly by the moving bow or our right hand. This does not cause a problem if the music has been read in advance, as it is necessary anyway. This rule, of course, is not set in stone, it can be altered if necessary, but in any case this is the most comfortable position.

Continuous Flexibility and Balance

If we fix a part of our body during violin playing (most often because of wrong posture or some tension resulting from another cause), we will not be able to remain continually in motion. Continuous motion, however, is of major importance: partly, as mentioned above, it ensures the maintaining of a balanced position and partly because preparation can only be based on motion.

The Movements of the Arms and the Joints in a Natural Direction

It is important to clarify which joints and parts of the arm can be used in violin playing and which is the most natural direction of their movement. We should always consider the direction of the swinging movement of the arm used when walking if we want to ascertain the correct direction.

- The shoulder and the armpit are perhaps the most complex joints from where we move the upper arm. Although we can almost turn full circle with our arm from the shoulder (that is we can almost touch from the inside around the shoulder joint an imaginary sphere, the radius of which equals the length of our arm) but this is not done solely by the shoulder joint: we have to raise the shoulder-blade and use the rotating motion of the collarbone originating in the breast-bone) The most natural direction of the motion starting from the upper arm is the oblique motion up and down in front of our body at approximately 45 degrees. In the case of a raised elbow (upper arm) the most natural movement for the upper arm is an immediate lowering, then a diagonal motion. We should avoid horizontal motion to the right and left. If we focus on the armpit instead of the shoulder, the sense of weight will be softer.

- The elbow is responsible for the position of both the upper and the lower arm. The lower arm moves right and left from the elbow in a half-supinated position raised to horizontal height (with the palm pointing left) and in pronated position raised to the same height (with the palm turned downwards) in about a 45-degree angle, up to the left and down to the right. The angle will change with the raising of the elbow/upper arm but it will generally remain at the level of the upper arm. Because of the articulated elbow the lower arm could be moved at a right angle to the upper arm (perpendicularly), but it is not a natural direction.

- The wrist moves the hand. The waving motion at a right ngle from the plane of the hand is natural, but the wrist is also capable of lateral movement on the level of the hand. In the pronated position of the lower arm the wrist angle may lean a little to the left.

- The back of the hand and the palm. The motion originates in the proximal joints which are capable of a limited amount of lateral movements. At the bow-shift we may need, for example, to pull the bow in one direction with the whole of the hand while the arm already moves in the other direction. In the left hand we use the back of the hand mainly for stretching or tightening or we move the hand against the thumb. As with the armpit, it is worth focusing on the palm instead of the back of the hand.

- The fingers basically move up and down but this movement is used mostly in the left hand. The right hand needs much more complex lateral movements especially in the case of bow change and to a minimal extent (but then very forcefully) in the case of springing bow.

The Fundamental Motions of the Right Arm

The movements of the two arms and hands affect one another; they are related (a familiar phenomenon is when, in a forte passage, the fingers of the left hand also exert more effort though even the opposite might be necessary), but we still have to discuss them separately. Partly because of their functional differences, partly because of their basically different positions: when playing the violin, the right arm is in a pronated, the left one is in a supinated position. The present section then is about the right arm but, of course, the mechanical principles are valid for the left side, too, as we will see in the next section.

The right arm has no other role than to operate the bow in the musically proper direction. That is, it has to bring the bow to a position in which it is unable to operate with a different weight, speed and in a different angle from the string than is optimal from the musical aspect. To achieve this, it is necessary to harmonise all the components of the right side. The aim is not the positioning and holding the hand, the elbow, or the shoulder, but the position of the bow related to the string and its continuous release.

It is the bow which is in direct contact with the sound, the centre of the resonant motion (the string) realising the sound; our fingers are in contact with the bow stick, and the sensation of the back of the hand, wrist, elbow, arm and shoulder only follow after these. That is, release begins in the string and proceeds throughout our right side. It does not begin in the shoulder where we are suspended. If we think this way, all those motions starting in the shoulder, upper arm, or lower arm which violininsts usually operate with seem completely pointless. Not to speak of the unnecessary muscle work in the right shoulder, arm and hand, which we often experience: the weight of the violin bow is only 60 grams, while the viola bow, which looks much heavier, is only 10 grams more. Still, most violinists make a big problem out of the the lifting of the bow.

By the way, how high to raise the bow? It is a generally observed mistake that violinists grip the bow hanging down although this definitely stiffens (because it is not natural) and forces the arm into a supinated position if the hair of the bow is turned outwards. The violinist, aiming at safety, believes to be preparing the proper holding of the bow but they only fix the stiffness instead even before approaching the string. The correct posture is flexible, meaning that the components of the body actually doing the work will have to be in the correct position at every point. In the present case we have to hold the bow lightly, just not let it fall and it should hang with all its weight. Hold it loosely like a stick and turned in an angle so that when we swing it up, the horse-hair should look downwards. And I do not lift my arm, nor my hand, after this, but I raise the appropriate part of the bow to the string. Since the straight line is the shortest between two points, to save energy and muscle force, the lifting of the appropriate part of the bow usually takes place forward and not to the side. The path is not completely straight. As my arm swings, the bow follows the curved line of the swinging arm together with the shoulder and the elbow. During the swinging, owing to the flexible grip of the bow, it almost falls into my palm and takes its place under my fingers. I naturally have to lift the bow (and my hand with it) higher than the violin (and not at the same level as an often be seen), so that I will only have to drop it in the proper falling angle.

It is important to make students conscious of the fact that the whole right arm is ‟one piece of machinery” from the shoulder to the contact point of the string and the bow. This machine transmits the weight of the arm to the string. If there is a break anywhere, the weight will be directed there. E.g. if the elbow hangs down, the weight will fall under the elbow and will not reach the string. In this case violinists try to compensate with pressing the index finger, which will only make the tone rigid, since this is pressing at the wrong angle and not a natural weight. What is more, because of the pressing and the incorrect elbow position, the lower arm is unable to move in the natural way described in the previous section.

The Position of the Left Hand, Preparation (Elbow, Arm, Fingers)

The corrrect positioning of the left elbow is the basis of intonation. There is only one exact point in the placing of the hand, which is the place of the note played on the fingerboard. The finger- pad has to be positioned there. The position of every other component (the non-playing fingers, especially the angle of the thumb and the hand, their height, the lower arm, upper arm and elbow) can be altered depending on what is comfortable and right for the given finger. Each note and the corresponding finger have their own optimal positions. And these are liable to change in the musical texture according to the length of the note, the tempo, dynamics or vibrato. Do not play the violin by placing your left hand in a certain position and trying to reach the various notes from there.

As with the right hand, it is also an important point in the left hand to hold the back of the hand and the fingers in their natural, half-spherical position. There are some exceptions, extended and exceptional positions (tritones, tenth doublestops, and certain chords), but change should always be measured compared to the natural position and that is also where we have to return.

The first problem the player meets is holding the instrument. Gripping is not useful because it may immediately turn into pressing. We also have to consider the opposition of the thumb and the upper fingers and the natural grip. The fingers, including the thumb, must surround the neck. This embrace and the sense of a loose palm (similarly to the loose armpit) will be a great help to finding the natural hand and finger positions.

The second problem is caused by the thumb. The thumb (like all the other components) ought to be in constant movement and change since the optimal position of each finger entails an optimal position of the back of the hand, the wrist, the arm and the elbow as well the thumb. And this position is a little bit (mostly only minutely) different in the case of each note. The optimal position of the thumb is indicated by the looseness of the palm. A thumb pulled too close to the body (for example, when it is opposite the ring-finger) will result in pulling down the upper fingers in the opposite direction, so that intonation will be low, our palm will tighten and harden. Other problems are when the thumb is pushed too low (towards the scroll), or when the thumb is placed too low or high compared to the surface of the fingerboard, resulting in a too low or too high arm position. There is no general rule, in addition to comfort and optimal position, for these situations, because the proportions are different for everybody considering the length of the fingers and the size and stretching of the palm. The positioning of the thumb in high positions is a separate problem. Depending on the size of the hand, some fix the thumb on the nut side of the rib and stretch the other fingers from there to the top of four-octave scales. Others bring out the thumb next to the rib, while those with small hands are suggested to slide it next to the fingerboard. I am very much against the latter solution, since it becomes impossible to position the playing fingers because the cushion of the root of the thumb and the pads of the playing fingers get too close, one on the top of the other, making playing unmanageable. This is dangerous because in the highest octave the fingers are hardly capable of correction by themselves; they fully depend on the elbow, the wrist and the thumb. The highest five notes of a four-octave scale can only be intoned with elbow motion even without moving the fingers.

The third problem lies with the palm. Even if everything is in place (elbow, wrist, fingers), the hardness of the palm may ruin it all. The palm can stiffen easily since there are no muscles on the back of the hand, only on the palm side (Szentágothai and Réthelyi, 2006, p. 323), so if there is work to be done, it is here. This is why our palm must remain as elastic as possible.

The fourth problem is the little finger. It cannot play with force and great speed; its cushion surface is also small, its capability for lateral motion is narrow, which makes vibrato hard to execute. Therefore we have to strengthen it (there is a whole library of exercises for that) but it is a problem of fingering also that, perhaps to strengthen the little finger, teachers make students play the fourth finger on the top notes. Whereas, on the top of a rising triad or in case of an upward large interval, playing the top note with the longer 3rd finger, which is at a more advantageous angle, is much simpler and more natural than the fourth finger, especially if it is a long-sustained, strong, vibrated note.The positioning and strengthening of the fourth finger involves a disproportionate elbow-motion and the body of the violin also has to be evaded, while the third finger can reach the required note without shifting positions, holding the thumb in place and only extending the back of the hand upwards.

Figure 3: Two excerpts from the Sibelius Violin Concerto

Examples for the extended 3rd finger used instead of the 4th

Many violin tutors and study collections mention the concept of leaving the finger on the string, which is marked in the music with a long line drawn after the given fingering notation. Since the natural position is placing all the fingers on the string or its vicinity with the hand forming a half-sphere, the finger to be left on the string results in an unnecesssary pressure with the majority of the students. The reason is that the end of our fingers do not touch the same straight line; the string under the fingers, however, forms a straight line. Since each finger cushion has its own natural surface, in my opinion the natural way is to place only the playing finger on a string (in one-part playing). The other fingers, even if they touch the string, are just positioned there without pressing. It is the same as when we walk: we step on one foot and when we have rolled forward on the one foot, the other foot will take over. There are plenty of cases, of course, when temporarily we need to use two fingers, for example in scale steps when using the fourth and the first finger of neighbouring strings, but in this case at the metric sounding of the next pitch we change for the following finger and this releases the preceding one, ceasing the sensation of the double stop (see Figure 2).

By the way, double stops: in case of the double stop played by two different fingers we naturally stay on two fingers, trying to find the optimal common hand and arm position of the two fingers in the same way as when we stand on two feet. We can easily move on and release with two fingers put down at the same time although it makes vibration more difficult. But in the case of playing chords with three or four fingers, there is no common position. Even if we play a four-note chord, we have to follow the chords with the left arm and roll over the string surfaces (normally upwards), while placing the optimal position from one pair of fingers to the other. Success and artlessness will mostly depend on the intensive motion of the elbow.

Finally, we should not forget, that most frequently the non-playing fingers are to be blamed for mistakes! Even if we position the playing finger correctly with the help of the elbow, we can ruin the result completely by placing the other fingers in a non-natural position or stiffening them. What is more, even if we place the fingers in the correct position but our hand is stiff, this stiffness will be audible, the sound will not resonate enough so we will not hear that it was in tune because of its tone colour.

Important Details

The Right Touch: Upwards

We have mentioned one of the most important questions, touch, only fleetingly. Touch is usually taught as the loose dropping of the fingers. This might seem true on occasion (when we play ascending steps on the same string), since the sound (especially with legato playing) will start when the fingers of the left hand are placed on the string. But even with descending steps the situation changes since the lifting of the upper finger coincides with the beginning of the following pitch, and in case of changing strings the new note usually sounds when weight is placed on the new finger (see Figure 2). The truth, in fact, lies mostly in the latter. That is, each note has a preparation in the fingers of the left hand and release starts at the lowest point of the sinking (at the releasing point) as discussed earlier. This is the release of the note, which ensures that the sound would be mellow and elastic. What is more, since, thanks to the release, the fingers (and, in fact, the whole palm and left hand) are in motion, using the kinetic energy of the movement, we can prepare the next note (i.e. the touch) without extra energy. This fundamental but on occasion extremely minute motion, which can sometimes only be sensed in the finger pad, is directed upwards. Again, the same as with walking. Soldiers may cut the heel of their feet into the concrete on command, but normally, when the ‟Left, right” command is sounded, we just spring up with our left or right foot and the putting down of the foot and rolling to the front have already taken place. The same way as we bring our feet in an optimal position for springing with the movement of our body, we position our fingers with the help of our arms and elbows. So, if we do not behave like soldiers in boots, we should not touch downwards, but release upwards.

Vibrato Downwards (Backwards)

There are many ways of teaching vibrato, but there are three main errors made by teachers: one is that they handle vibrato as a separate movement, dissociated from intonation, the other is teaching it as an arm or elbow motion at the beginning although the basis of any vibrato is swinging on the finger pad, and the third is starting the vibrato upwards.

The latter results in many violinists intoning vibrated notes higher or, if they have a good ear and are attentive, they will place their hand lower. In that case, however, their intonation will be low when playing non vibrato. (I have often heard a whole violin section playing uniformly low at rehearsal when the conductor asked them to play without vibrato in order to make intonation clearer. It turned out that they all intoned with a vibrato in the wrong direction and without vibrato none of them could find the proper place of the pitches on the fingerboard.) Vibrato then means the changing of the actual pitch of the note downwards. It is the trills that change the pitch upwards (but then the difference is exactly a semitone or a whole tone). The ear will perceive the higher pitch and in case of vibrato that will be considered the real pitch of the note (with the trill we can perceive both pitches). It is fortunate if the original pitch (the top of the vibrato) is sounded on the small division values, so a rhythmic (metric) vibrato is not a disadvantage. This is not compulsory and is not always effective, but if we play in tune on the beats, the ear will more readily interpret the original pitch of the vibrated note. With a downward stroke, it is relatively easy to start vibrato with a downward movement (in the direction of the scroll, that is away from our body), as we do not feel it unnatural because of the contrary motion of the two arms. Starting vibrato downwards (backwards) when playing up-bow, is more problematic but can be learned with some attention.

The basis of all three kinds of vibrato (finger, wrist and arm) is swinging on the finger pads. (I am not speaking of the vertical finger and bow vibrato, used in Baroque playing – they are mostly of stylistic rather than of technical interest.) It does not matter whether the wrist or the arm are involved in the swinging motion; the swinging and the contact with the string have to be felt on the finger pads the same way. Vibrato, in theory, should take place in the direction of the string but we can observe that this is only valid for wrist vibrato. Downward finger vibrato is distorted a little bit towards the lower strings (backwards to the left) and downward arm vibrato is distorted towards the higher strings (backwards to the right). It is important to notice that wrist vibrato does not stem from the wrist, neither does arm vibrato start in the arm. We have to lengthen the ‟starting arm” utilizing the waving motion of the wrist, or the arm motion starting in the elbow joint, forming an organic unity (‟machinery”) from the finger pad to the articulated joints in the wrist or in the elbow. This presupposes some firmness in the hand, especially in the back of the hand, but it is important that it should not transform into stiffness (as seen so often, mainly with arm vibrato) because then the fingers also begin to press.

As a matter of fact, vibrato is a natural continuation of touch. We have to carry on the release of the touch through the direct sensation of the finger pad, which actually touches the string. Whether this sensation is taken further than the finger and becomes an elbow or arm vibrato will depend on the depth of the touch from the point of mechanism. Otherwise it mainly depends on musical considerations, since the larger the joint we vibrate with, the larger the amplitude and slower the speed of the vibrato will be (lower frequency). There is a little contradiction here: because of the limited capability of the fingers, finger vibrato is the slowest. With attentive and patient practice we have to learn to conquer our vibrato, we have to be able to change its amplitude and speed and imperceptibly shift from one type of vibrato to the other. In addition, we also have to learn to execute vibration gradually, and even use it contrary to the speed of the bow (for example have a sound carry on with vibrato only when the speed of the bow has decreased or the bow does not even move or touch the string).

The Relation between the Bow and the String, the 4+1 Parameters

We have discussed the vertical relationship of the bow and the string (sinking and release) earlier, but it is also important to know how and according to what parameters this relationship can be altered. The conscious use and alteration of these parameters contribute to the richness of the tone, and are indispensable conditions to artistic performance. The four parameters of bow-stroke are:

- weight

- speed

- distance from the bridge

- the amount of horsehair

- (+1): the falling angle

No. 5. may require some explanation. This angle is between the surface of the string (level) and the direction of the pressure (weight) provided by the bow at the point of contact where the bow touches the string. If this angle is at 90°, there is no sound because the weight goes straight into the string. If the angle is broadened to the left (from the left), a downward stroke is generated, if it is broadened to the right, it becomes an up-bow. With the sensation of the angle of incidence we can avoid starting the stroke from the arm, instead, the bow will ‟pull itself” as a result of the release without the player doing anything.

An excellent way to practise the four parameters is to play altering p-(crescendo)-f-(decrescendo)-p, or f-(decrescendo)-p-(crescendo)-f with whole bow, using strictly one parameter at a time. Once this is done well, we can combine the parameters and play contrasting dynamics with them (for example, increasing weight when decreasing speed and vice versa). The theory and practice of the four parameters originate with the Austrian violinist, Thomas Zehetmair (who presumably learnt it from his father, Helmut Zehetmair).

The Use of Bow Places, Springing Bow

Different bow places have to be chosen in such a way that we feel that the flexibility of the stick and the bow plays everything by itself. Violinists usually play too much with the arm and think horizontally instead of vertically, so they work superfluously many times. Discussing this problem and that of various bow-strokes would require a whole book. Here we will only mention two fundamental points, the realization of which is indispensable to correctly executing bouncing bow-strokes: the stick is jumping up and down but its flexibility is ensured by the tightness of the horsehair. Like a ball, which will bounce when inflated but will just ‟sit down” when flat, if the bow is turned extremely outwards (when we play with one single hair), it is as if we let the air out of the ball. The stick will still jump up and down, but now it will fall on the strings by and the hair, which is good with col legno, but not at all suitable for the bouncing bow. The other important point is that in a normal bow-grip we basically hold down, even suppress, the up and down motion of the stick with our fingers above the stick, making the jump impossible. So, in case of bouncing bow-strokes (at least, if we want to use the flexibility of the stick) we have to hold over a little and place our fingers on the other side of the stick. For this we need a somewhat higher wrist position but it is important not to keep to the original angle of the fingers compared to the bow because then we would practically turn the original grip further and, even worse, the stick will turn over the horsehair, so we will try bowing on one single hair. Instead, we need a new grip, which can immediately be altered, when only the little finger is placed above the stick, the other fingers are on the other side. Control comes from the skewed index finger from above, which does not press the stick down but holds it and does not allow jumping too high over a certain point thus regulating the tempo of the bounce.

How (Not) to Sit?

In an orchestra and when playing chamber music violinists (and viola players) are usually advised to sit on the edge of the chair so that their spine is straight and to place their right leg in between the right side legs of the chair. This could be correct in theory but practice shows that the instruments will hang down in this position. What is worse, this way of sitting is distorted and stiff, which affects every muscle. The right leg has to be bent lower, so that the bow should have enough room. Support on both feet and a straight spine are all right but I believe it is not wrong either if we sit further back on the chair with our back touching its back so we could even lean on it if necessary, feeling the back of the chair with our shoulder-blades and holding the instrument upwards without effort. (This is somewhat contradictory to the idea represented by my honoured colleague, Dr. György Sárosi, see Sárosi, 2011, p. 107) Comfortable seating (but not sprawling) also helps sensing the low centre of gravity, freeing the arms, and it is especially useful when playing in high positions and at the nut. It is not wise to point the scroll in the direction of the music-stand because then we can only see the music if the instrument is hanging down. It is better to play looking straight forward and looking at the music over the bow and our right hand as discussed in the section about holding the instrument.

Summary

If I had to summarize the above briefly, I would only enumerate a few basic principles which give a solution in EVERY case if understood and used correctly, independent of the level of the player and the difficulty of the material.

- Sound is release. This defines every motion connected to the creation of the sound from preparation through tension created by weight to the actual release.

- Gravity is the violinist’s best friend. Weight works downwards. Play with vertical sensations.

- Music is motion. Movement can only be born out of movement (preparation). Each sound (movement) is the result of the previous sound (movement) and the preparation of the next sound (movement).

- Every movement must take place in the natural direction of the part of the body performing it, and the components not taking part directly in the movement (like the non-playing fingers) should also take the most natural position.

- Small joints (like the finger) are positioned correctly with the large joints (arm, elbow). Mechanically speaking, we intone the sound primarily with the elbow.

I do hope that by now it is clear for every reader that the understanding and proper realisation of the mechanical principles summarised in this study will result in free and soaring violin playing and a natural, big, round and resonant sound. You will realise that sound production is basically not ‟making but letting”. So we do not have to work on sound production separately. It is very important, at the same time, to attribute the realisation of sound to the harmonious cooperation of our arms, hands and fingers. and even to our whole body. We cannot equivocally state that the right side produces the sound and the left is responsible for intonation and rhythm, as many people are trying to separate these functions. The right side obviously plays a greater role in breathing but, considering the quality and timbre of the sound, the left hand, the vibrato are equally important ‟accessories”. As I have mentioned at the beginning of this article the sound has a spectrum which cannot be taught, and it cannot even be explained how a violin sound becomes special, individual, attractive or poignant. Anyway, no good sound contradicts any of the described fundamental mechanical principles and one cannot produce good sound without them, if the use of the term sound production is still valid at all.

And, finally, one more idea (a commonplace but a very important one): even the most beautiful tone does not guarantee a stylistically and emotionally apt musical interpretation. We can hear violinists who are mechanically perfect and have a beautiful tone but their playing is musically empty, as if they only played for the beauty of the sound, finding in it the meaning of music-making (or rather, only violin-playing). This is obviously a cul de sac. A good tone is only the basis, the starting point to the correct interpretation of music. After proper mechanism the role of intelligence, musical (harmonic, formal and stylistic) sensitivity and knowledge, intuition and creativity come into the forefront.

References

- Johnson, Jennifer (2009): What Every Violinist Needs to Know about the Body. Gia Publications, Chicago, USA.

- Sárosi György (2011): A hegedűjáték történeti, pedagógiai és módszertani háttere [The Historical, Pedagogical and Methodological Background of Violin Playing]. Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó, Debrecen.

- Szentágothai János & Réthelyi Miklós (2006): Funkcionális anatómia [Functional Anatomy] I. (Eighth edition.) Medicina Könyvkiadó Zrt., Budapest.

Websites: