Author: Levente Puskás

DOI: 10.5434/9789634902263/15

Abstract

The saxophone is one of the most popular, almost ubiquitous instruments of our time. It is unimaginable that the saxophone would not appear in an orchestra or band in jazz, popular music, dance music, pop music, or even folk music. It is not widely known, however, that the story and history of the saxophone dates as far back as around 170(!) years ago. In 2014 the 200th birthday of Adolphe Sax the inventor, after whom the instrument got its name, was celebrated. Sax was the first saxophone professor at the Conservatoire de Paris. For most of the 19th century, mostly Classical and Romantic pieces were usually played by the saxophone, as the genre of jazz came into existence only around the 1910s–1920s. At that point classical and jazz (popular) saxophone music separated. Differences between the two styles can still be observed in both musical approach and technique. This study presents the similarities and differences between these two highly distinct approaches.

Keywords: saxophone, Adolphe Sax, classical music, jazz

Introduction

The saxophone is one of the most popular instruments of our time. If we turn on the radio or television, or visit any website, we are likely to encounter its sweet-voiced, charming, sometimes metallic and crude sound, as it is almost unimaginable that the saxophone should not appear in an orchestra or band in jazz, popular music, dance music, pop music, or even folk music. However, it is not widely known that the story and history of the saxophone date as far back as about 170(!) years; what is more, it was more than four years ago when Adolphe Sax’s 200th birthday was celebrated, who was the inventor, after whom the instrument got its name, and who, incidentally, was the first saxophone professor at the Conservatoire de Paris. As it is now evident, Sax created the instrument in the middle of the 19th century, when the musical styles for which the saxophone is now cardinal did not exist yet. Therefore, the question arises as to what genres and styles of music were played on it for 70–80 years, until jazz appeared in America in the early 20th century.

Generally speaking, the saxophone was included in certain Classical and Romantic pieces. It was Hector Berlioz who was one of the first to stand by Sax’s invention completely, but George Bizet, Maurice Ravel, and Claude Debussy also composed works for the saxophone. The rise of jazz in the 20th century became the turning point when classical and jazz (popular) saxophone music separated. Differences between the two styles can be observed still in both musical approach and technique. In this study, I present the similarities and differences between these two highly distinct approaches.

The History and Development of the Saxophone

Adolphe Sax, the Creator of the Saxophone

Adolphe, Charles and Maria Sax’s first child, was born on 6 November 1814, in Dinant, in what is now Belgium. Shortly after Adolphe’s birth, the family moved to Brussels in search of a better life and opportunities. Adolphe’s father was an instrument maker, who repaired and made various sorts of woodwind and brass instruments. Even as a child, Adolphe spent considerable time in his father’s workshop, where he often helped repair the instruments. Upon his father’s suggestion, he applied to the Royal Conservatory of Brussels, where he studied singing, clarinet, and flute, but his interest quickly shifted to the physiology and acoustics of instruments. Adolphe was fascinated by the prospect of creating a new instrument which would merge the positive characteristics of woodwind and brass instruments and could be used in concert halls as well as outdoors. He thought the new instrument should be able to produce a sound as gentle as the flute but also as forceful as the horn or the trombone. He began experimenting around 1834 by uniting a conical brass body with a single-reed mouthpiece, which resulted in the instrument he named saxophone after his surname. He made the instruments in multiple sizes, thus creating an instrument family. Originally, they were pitched in C and F. Later he created versions pitched in E-flat and B-flat, as the instruments were mostly used in brass and reed bands, where most instruments were and still are pitched in E-flat and B-flat. As a consequence, there exist E-flat sopranino, B-flat soprano, E-flat alto, B-flat tenor, E-flat baritone, B-flat bass, and E-flat contrabass saxophones. Of these, the most frequent are soprano, alto, tenor, and baritone saxophones, which also constitute the widely popular saxophone quartet formation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Soprano, alto, tenor, and baritone saxophone

Sax decided to present his newly invented instrument at the Brussels World's Fair in 1841. His hopes of receiving considerable interest and international success were not unfounded. The first appearance of the saxophone became a remarkable success. Sax’s invention was awarded the Gold Medal, the greatest prize at the World’s Fair.

There are several hypotheses as to how Adolph Sax created the saxophone, more specifically, as to which instruments he developed further to arrive at the new instrument. According to one theory, the precursor to the saxophone is an Argentinian instrument, which has a cow’s horn body and is sounded by a single-reed mouthpiece.

Another hypothesis suggests that the precursor to the saxophone is the alto fagotto, which was designed by William Meikle and produced for the first time in 1830 by George Wood, an instrument maker in London. The instrument had a conical bore wooden body with a single-reed mouthpiece. The third possible instrument was made in 1807 by Desfontenelles, a clock maker in Liseux. This instrument had also a conical wooden body with a simple clarinet mouthpiece. Its design was different from that of the saxophone because it did not overblow at the octave but at the twelfth like the clarinet. The instrument is currently displayed in the instrument collection of the Conservatoire de Paris (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Desfontenelles’ instrument

The final instrument to have been considered as a predecessor of the saxophone is the Hungarian tárogató. The sound was originally produced on the instrument by a double-reed mouthpiece, which was modernised by József (Joseph) Schunda, an instrument maker in Budapest, at the beginning of the 20th century with a simple single-reed clarinet mouthpiece. Besides the redesign of the mouthpiece, Schunda also altered the key system (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Schunda’s tárogató

The world-famous American saxophone artist and teacher, Frederick Hemke mentions three possibilities which could have led the way for Adolphe Sax’s instrument. According to the first possibility, Sax started out from the clarinet and tried to transform its conical brass version to overblow at the octave instead of the twelfth. Hemke’s second possibility suggests that Sax placed a clarinet mouthpiece on a rudimentary bassoon, which became the saxophone. According to the third theory, which has since been corroborated, Sax started out from the conical brass instrument ophicleide (ophikleid), which was quite popular in the 19th century, and supplemented it with a clarinet mouthpiece, which resulted in the new instrument (Fred Hemke, 1975) (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The ophicleide, predecessor of the saxophone

The first instruments produced were pitched in C and F, which were quickly replaced by versions pitched in E-flat and B-flat, as it was much easier to play instruments pitched in E-flat and B-flat in wind orchestras (where the saxophone was and still is used the most) for reasons of technique and intonation.

When Adolphe Sax presented the new instrument in 1842 in Paris to Hector Berlioz, a great composer of the era, Berlioz was highly impressed. He even mentioned the saxophone in his Treatise upon Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration (Hector Berlioz, 1848).

Naturally, Sax presented his invention to numerous composers, many of whom became interested in the new instrument. Besides Berlioz, those who familiarised themselves with the instrument include Bizet, Rossini, Auber, Fetis, and Kastner. As it is known, George Bizet (1838–1875) used the instrument in his L’Arlésienne. It is important to mention the talented French composer and flautist Jules Demersseman (1833–1866) and the Belgian composer Jean-Baptiste Singelée (1812–1875). Demersseman composed various works for the saxophone (e.g., Fantaisie Op.32, Allegretto Brillante Op.46, Introduction et Variations sur “Le Carnaval de Venise”, Fantaisie sur un théme original, etc.). In addition, he also created a primer of etudes titled 12 Études Mélodiques et Brillantes. Through their virtuosity, these works allow players to demonstrate their technical ability and are considered to pose a sizable challenge even to contemporary saxophone artists. This implies that it was possible to play Sax’s instrument quickly even at the time of its creation, and that there were exceptionally talented virtuosos as early as the second half of the 19th century who could interpret such works. Jean-Baptiste Singelée also enriched the repertoire of the saxophone with several pieces for the instrument (e.g., Fantaisie Op.50, Concerto No.1, Concerto No.2, 1er Solo de Concert, 2er Concert, Fantaisie Brillante Op.86, Fantaisie Pastorale, etc.); what is more, he composed the first piece for a saxophone quartet, namely the Grand Quatuor Concertant No.1, Op.53.

Sax popularised his instrument constantly, even by presenting it at fairs and performing himself. In 1867, he enjoyed spectacular success when he presented the instrument at the International Exhibition in Paris: he was awarded the Grand Prize. After Adolphe Sax’s death in 1894, his son, Adolphe Edouard took over the family business and the factory. Of Sax’s three children, Charles was born in October 1856 but died in 1858, and Adele was born on 29 November 1858. Adolphe Edouard came third on 29 September 1859. He continued his father’s business until 1928, when he sold the factory and the manufacturing rights to Henri Selmer.

The Selmer Family’s History

The Selmer family’s history goes back to the 17th century. Johannes Jacobus Zelmer, Henry Selmer’s great-grandfather, was born in the Lorraine region of France and served as a soldier. It was his son, Jean-Jacques Selmer, a military musician, who changed the name from Zelmer to Selmer. Jean-Jacques’s son (Henri’s father) was Charles-Frédéric, also a military musician, who tragically died in 1878. Of his 16(!) children, only 5 survived to adulthood. Henri (Figure 5) and his brother Alexandre (Figure 6) studied clarinet at the Conservatoire de Paris. After graduating from the conservatory, Henri (1858–1941) was employed in the French Republican Guard Band, founded by Napoleon, and at the Opéra Comique. At the beginning of the 1900s, he opened an instrument shop in Paris, on the Place Dancourt. He sold reeds and mouthpieces he produced and also took on repair and renovation work for clarinets. As he could fix the instruments at a high quality, the shop soon became popular, and he even began to manufacture his own clarinets. Due to the rapid expansion of the company, a new factory was established in 1919 in Mantes, 30 kilometres from Paris. In 1928, when he purchased the manufacturing rights of the saxophone as well as the corresponding factory, the company started to produce saxophones as well.

Alexandre Selmer’s (1864–1964) career took another path. Between 1895 and 1910, he worked as principal clarinettist in renowned American orchestras (Boston Symphony Orchestra, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, New York Philharmonic Orchestra). At the beginning of the 20th century, Alexandre managed to open a Selmer instrument store in New York. The instrument produced by the family for the Saint Louis World’s Fair was awarded the Gold Medal, which brought prosperity for the company. In the 1920s, the production of flutes also began. In 1940, they entered the market for pianos but ceased their piano production in 1954. In the 1960s, the Selmer company reached the peak of its popularity and purchased multiple great instrument manufacturers such as the Vincent Bach Corporation (1961, brass instrument manufacturer), Buescher Band Instrumental Company (1963), Brilhart Company (1966, mouthpiece manufacturer), Glaesel Company (1977, string instrument manufacturer), and the Ludwig Company (1981, percussion manufacturer).

Figure 5: Henri Selmer Figure 6: Alexandre Selmer

The Acoustic Characteristics and Technical Development of the Saxophone

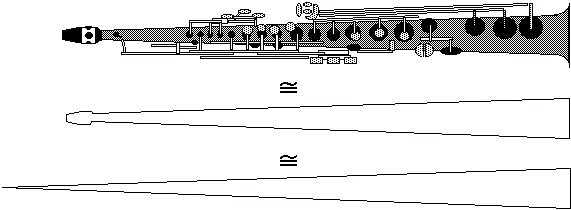

Many laypeople believe that the way the clarinet and the saxophone is sounded is similar and a clarinettist can play the saxophone without difficulty, since both instruments have a single-reed mouthpiece. I must contradict this presumption. The bore of the clarinet is almost cylindrical, that is, parallel until the bell (Figure 7); the bore of the saxophone, by contrast, is conical (Figure 8).

Figure 7: The cylindrical inner bore of the clarinet

Figure 8: The conical inner bore of the saxophone

Naturally, the fingering is not the same for the two instruments, due to differences in the bore. It is easier to produce lower sounds and play piano (quietly) in the lower register on the clarinet than on the saxophone. Producing higher sounds (in the so-called flageolet register) is relatively difficult on both instruments and requires considerable practice, although it is somewhat easier in the case of the clarinet.

Interestingly, the technical development of the saxophone in the early years was hindered by the fact that Adolphe Sax’s company had exclusive manufacturing and development rights for the instrument until 1866. Evidently, this was lucrative for the Sax family, but other companies were denied the possibility of carrying out developments. It was only after the exclusive rights were lifted when other instrument manufacturers could begin to produce and further develop the saxophone.

In 1877, the Evette & Schaeffer Society implemented several changes on the saxophone. Their instrument was among those which solved the problem of F–F-sharp trills by installing on the instrument the so-called F-sharp trill (Tf) key (Figures 9a and 9b), which enables players to sound the chromatic sequence of F–F-sharp–G in a comparatively effortless way. The key which facilitates the sounding of B-flat4 by the left hand only is also attributed to the same company (Figure 10)[1].

In 1888, A. Lecomte and Company found a way to resolve the problem of how E-flat4 and C4 can be played in succession: both keys were equipped with a roller, which lets players roll their right little finger from one key to the other (Figure 11). It must be noted that on saxophones produced by the manufacturer Buffet, the E-flat4 and C4 keys form a U-shape together, which allows the right little finger to easily turn from one key to the other, thereby producing the two sounds without a gap in between. Besides E-flat4 and C4 notes, the same applies for playing the following combinations successively: E-flat4 and C-sharp4, E-flat4 and B3, E-flat4 and B-flat3.

From 1928 on, the Selmer company pioneered saxophone production, accompanied by several technical innovations. In the 1950s, three major developments were implemented, which are still used today by all saxophone manufacturers.

The key invention was the connection ring (Figure 12), which enabled the separation of the straight body of the instrument from the bow and made the repair of dents and other damages easier. At the time, the innovation divided musicians and instrument manufacturers because many believed it would become the “weak point” of the instrument. According to critics, the ring would cause a “rupture” on the body, which previously “vibrated in an undivided way”, thus breaking the uniform sound; moreover, the air could “escape” at the connection of the body and the bow, making it even more difficult to produce the sounds in the lower part. Instrument makers, however, welcomed the innovation as it enabled them to repair damaged saxophones more easily and more quickly.

Figure 9a: F-sharp trill key from the back

Figure 9b: F-sharp trill key from the front

Figure 10: The left-hand B-flat key

Figure 11: Rollers on the C and E-flat keys

Figure 12: The now separable body and bow of the saxophone

The Arrival of the Saxophone in America; the Era of Dixieland and Early Jazz

When Adolphe Sax filed a patent for the saxophone in 1841, jazz was nowhere to be found. However, the genre of jazz, which originated in the early 20th century in America and later became prevalent and prominent there as well as worldwide, brought widespread fame and popularity for the instrument. What is jazz, we may ask, and how did the genre come to life? Naturally, this study does not aim to reconstruct the origins of jazz but still offers an outline of it, since I am convinced that jazz musicians have played a pivotal role in spreading and popularising the saxophone, which is why some knowledge on the topic could be helpful.

To better understand the origins of jazz, we must go several hundred years back in time. In the 16th century, after the discovery of the North America, European (e.g., English, German, Dutch, French) settlers swarmed the Northern part of the continent, also importing their musical culture. It should be kept in mind that it was the era of the Baroque at the time in Europe. Settlers, whose plantations were in dire need of labour, waged war with indigenous people and caused them severe casualties. As a consequence, people were brought (forced) from Western Africa to America for their labour. Slave trade soon became a profitable enterprise. For a century, until 1619, slaves were usually transported to Virginia, but later slave trade mostly relocated to Southern regions. Slave trade was legal until 1807 but was abolished subsequently. This did not mean that trade stopped and blacks were not forced into slavery anymore; but only that “a black market emerged for procuring and selling black people” (András Pernye, 1964).

As a result of history, European culture met the culture from Africa; in other words, European American culture was influenced by African American culture even from its origins. As the two cultures had an effect on each other, their combination also emerged. On the one hand, European settlers brought folk songs and religious songs from the Old Continent; on the other hand, ancient work songs and religious songs arrived from Africa. Several chroniclers wrote about black people’s collective musical activities and dances. An excerpt from the German musicologist Alfons Dauer’s book Jazz, die magische Musik (Alfons Dauer, 1961) provides insight into the musical habits of a black community in New Orleans: “The slaves usually begin arriving at Congo Square an hour or so before the scheduled time of the dancing, with the men strutting proudly in their castoff clothes given them by their masters and the women in dotted calicoes, wearing bright-colored Madras kerchiefs tied about their hair to form the popular headdress which the Creoles call the Tignon. The slaves bring their children with them, dressing them in old garments blighted up by colorful feathers or bits of ribbon. The spectacle never fails to draw the hawkers of refreshments... Then on a signal from the police officials, the slaves are summoned to the center of the square by the rattling of two huge beef bones upon the head of a cask, out of which has been fashioned a sort of drum or tambourine called the Bamboula. This rattling changes to a steady beat of the drums. The dancers begin doing their dancing as the drummer, without a pause and no break in the rhythm, continues until the sunset ends the festivities. The women, scarcely lifting their feet from the ground, sway their bodies from side to side and chant an ancient song as monotonous as a dirge. Beyond the groups of dancers are the children, leaping and cavorting in imitation of their elders, so that the entire square is an almost solid mass of black bodies stamping and swaying to the rhythmic beat of the bones upon the cask…”

Unsurprisingly, European settlers could hear the slaves’ work songs on the plantations. It is important to note that black people’s music was a collective art, which accompanied their gatherings, formed an integral part of their life as slaves, and also offered solace to them. Singing, music, and dancing were just as natural and important for them as food or drink.

Musical expertise provided black people a way to obtain higher social status. Many of them started playing cheap instruments which could be bought easily (violin, clarinet, trumpet, flute). Records from as early as the late 18th century show that some black players became famous and were also relatively well-off. European scales were introduced into African American culture through instruments.

New Orleans, Birthplace of Jazz

“…jazz was not born in New Orleans. It has its roots in African American instrumental music, while it is also based on the characteristics of orchestration in European wind orchestras. As the origins of jazz were concealed for a long time, it became customary to regard New Orleans as the birthplace of jazz…”, writes the aforementioned German musicologist, Alfons Dauer. It is no wonder that determining precisely the origin of a branch of art both spatially and temporally is quite complicated. Jazz is no exception to this. It can be answered, however, as to why jazz became so prominent in New Orleans.

The fact that New Orleans was a city unparalleled in its internationality in America and it also housed the largest and busiest slave market in the 18th and 19th centuries was the main reason for the emergence of such a mixed genre. Besides black slaves, the population also consisted of German, French, Spanish, Italian, and even Polish and Russian people. What is more, these nationalities also appear in records about musicians from the period. It follows directly that melodies in jazz display influences from French and German folk songs, Irish and English ballads, as well as French psalm tunes. As a result, listeners from almost any country can find familiar and beloved melodic phrases in jazz.

As the French influence was dominant in New Orleans, it is important to note that wind orchestras there were made up of almost identical instruments as French ones, namely the clarinet, oboe, cornet, flugelhorn, basshorn, trumpet, flute, and the piccolo. Naturally, each orchestra, from black folk bands to French wind ensembles, had a different number and selection of instruments. For a long time, orchestra members played music as a side activity and had a primary occupation. It was only at the turn of the 20th century when musicians could “specialise” and make a living from this profession, which is in close connection with the accelerating development of urban culture. By that time, a distinct entertainment industry had emerged in New Orleans, which was famous all across America. In 1897, the New Orleans City Council decided to concentrate and confine such “establishments” in a specific part of town, which was located next to black neighbourhoods (where clubs and public houses were also common). Various people were employed in public houses: musicians, waiters and waitresses, cleaning staff, and prostitutes were mostly black. Such neighbourhoods were called “Storyville”. Certain talented jazz musicians were awarded the title “the King”, sometimes even accompanied by a special crowning ceremony.

Saxophone and Jazz: Distinguished Jazz Saxophonists of the 20th Century

There is no other way to put it: the real recognition of the saxophone has occured due to its use in jazz. If an ordinary person is asked anywhere in the world as to how old of an instrument the saxophone is, the answer is expected to be that it probably originated in the 20th century as it is used in popular music, dance music, and jazz. As I explained it in the introduction, when Adolphe Sax created the saxophone family, he could not even dream of the success which the instrument received in the 20th century (or could he?). By then, jazz had not emerged, either.

It can be argued that the history of the saxophone in the 20th century is intimately tied to that of jazz as well as to the history and music history of the United States.

The first influential jazz saxophonist to be introduced is Sidney Bechet (1897–1959).

“There is in the Southern Syncopated Orchestra an extraordinary clarinet virtuoso who is, so it seems, the first of his race to have composed perfectly formed blues on the clarinet. I've heard two of them which he elaborated at great length… I wish to set down the name of this artist of genius; as for myself, I shall never forget it: it is Sidney Bechet.” These words were written by Ernest Ansermet, one of the greatest conductors of the 20th century, who premiered most of Igor Stravinsky’s works and conducted Bartók’s and Honegger’s compositions regularly.

The question may arise as to why a clarinettist is mentioned in a chapter about distinguished saxophonist. The answer is that Sidney Bechet, who began his career in the Southern Syncopated Orchestra as a clarinettist, “turned” from the clarinet to the saxophone around 1918 and became one of its great masters. He had an exceptional talent for the instrument, which had not enjoyed universality previously even in jazz. Bechet was raised under the influence of French culture in a relatively wealthy creole environment in New Orleans. Music historians agree that his upbringing and environment as well as his extraordinary musical abilities all contributed to his exceptionality. He visited Europe for the first time in 1919, when he toured in England and several other European countries. Subsequently, he spent two years in Paris (where Ansermet heard him and wrote about him in a study), and returned to the United States in 1922. Due to the Great Depression, he worked as a tailor(!) between 1933 and 1934, but soon thereafter he became a demanded musician again and could make a living from music. In 1947, he decided to move to Paris indefinitely, where he died in 1959. In France, many mourned his death.

The next distinguished saxophonist to be mentioned is Johnny Hodges (1906–1970) (Figure 13). Hodges played the alto saxophone, and was principal alto saxophonist and soloist for the Duke Ellington Orchestra between 1928 and 1970. Duke Ellington selected each member of his orchestra with utmost scrutiny; only the best could join. Ellington composed each musician’s part himself. Although Hodges left the orchestra for four years in the 1950s, it meant still a tremendous honour and achievement for him that he was principal alto saxophonist for the most influential and demanded orchestra of the time. It must be kept in mind that honour and respect were not the only attributes to the “jazz lifestyle” as it also required physical and mental fitness for 38 years.

Figure 13: Johnny Hodges

Experts recognise that Hodges brought a new style to how the saxophone is played by utilising every register of the instrument and by improvising in every key with astonishing confidence. His early and late improvisations display differences, however. While the young Hodges played and improvised at an astounding pace, his later solos are more transparent, calculated, and straightforward. His technique had substantial influence on world-famous saxophonists of later generations, including Jan Garbarek and Eric Marienthal.

Coleman Hawkins (1904–1969) was an outstanding jazz saxophonist of the 20th century, who even earned the title “father of the tenor saxophone” (Figure 14). His career began in Kansas City in 1920. It was around that time when Rudy Wiedoeft recorded the variety of capabilities the saxophone could offer (vibrato, double tongue technique, virtuoso technique, slap tongue), which affected Hawkins so deeply that he attempted to implement these techniques using his instrument, the tenor saxophone. For ten years from 1924, he was solo tenor saxophonist for the renowned Fletcher Henderson band. On Jack Hylton’s invitation, who was an Englishman, he went to Great Britain to work in the Jack Hylton band between 1934 and 1939. The band gave numerous concerts in Europe. In 1939, Hawkins returned to New York and worked on studio recordings with several groups. Around 1939, he gave up the slap tongue technique, which he had used extensively. He had an exceptional talent for expressing human feelings and emotions through his performance. Listeners may even get the impression that he is telling a story. A great example of this is his recording titled Body and Soul from 1939, which is among his most influential ones. In 1944, he produced a recording with Dizzy Gillespie, a significant trumpetist of the period, who was greatly affected by Hawkins.

Figure 14: Coleman Hawkins

Lester Young (1907–1959) was a similarly influential jazz saxophonist (Figure 15). Initially, he played the C-melody saxophone but changed to the tenor saxophone. His goal was to re-create the sound of the C-melody on the tenor saxophone. This novel and somewhat lighter tone inspired various saxophonists. Young’s other major innovation was how he alternated between quick and rhythmic improvisational patterns and slow-paced improvisations. Unlike his predecessors, he found a way to use vibrato in a varied way; he did not even vibrate some sounds, which contradicted the general approach of the time. He started his career in the Midwest of the United States, where he played in various bands. In 1928, he met Count Basie and joined his band briefly in 1934. In 1936, he joined the band again and played there until 1940.

Figure 15: Lester Young

We have arrived at one of the greatest jazz saxophonists (if not the greatest), namely Charlie “Bird” Parker (1920–1955) (Figure 16). He and Dizzy Gillespie are considered to be creators of the bebop style. Parker’s nickname, “Bird”, was given to him by his fellow musicians in reference to his virtuoso technique. He was born in Kansas City in an impoverished family, which is why he started to play in an orchestra at only 15. As he put it in his memoire: “I had to play music from 9 in the evening to 5 in the morning without a break for a mere dollar and 25 cents a night…” (András Pernye, 1964). As a teenager, he was largely influenced by Lester Young, who had become famous by then. He also liked Confessin’ the Blues, a sort of creed for the New Orleans era of jazz from 1941.

Figure 16: Charlie Parker

Interestingly, Gillespie, who had a similar style, enjoyed greater success than Parker. While Gillespie was a celebrated musician of the time, Parker was an “unrecognised genius”. Parker knew, felt, and often even wrote about his misfortune, which accompanied him from his debut: “I lived in constant panic, mostly stayed in a garage, and simply couldn’t manage. The most terrible of all was that nobody ever understood my music” (András Pernye, 1964).

Regrettably, Parker was heavily addicted to alcohol and drugs, which caused his premature death at 35. During his autopsy, doctors could hardly believe that the body belonged to a 35-year-old man and not a to 53-year-old.

An interesting addition to Parker’s biography must be mentioned: his favourite composers were Brahms, Schönberg, Stravinsky, and Hindemith.

Despite his short life, Parker had a profound effect on jazz saxophone performance as well as on the development of jazz itself. Alto saxophonists look up to him to this day; he was even an idol for John Coltrane, who was tenor saxophonist. The bebop style on the saxophone originated from Parker. Generations of saxophonists have tried to imitate and perform his impressive and oscillating solos. As Leonard Feather, famous jazz pianist, journalist, and producer of the 20th century, rightly notes: while several stars have used his style to shine, he could perform only occasionally and lacked a steady income.

The next great jazz saxophonist to be mentioned is John Coltrane (1926–1967) (Figure 17). He worked for years with Miles Davis, an outstanding trumpetist of the time, and Thelonius Monk, the renowned pianist. He began to develop rapidly paced improvisations. In addition, he is also considered to be the reinventor of modern jazz. Although he played in multiple orchestras until 1955, including Dizzy Gillespie’s and Johnny Hodges’s bands, his talent was not discovered. Since recordings by Miles Davis made a strong impression on Coltrane, he felt great honour and joy when he received an invitation from Davis’s band in 1955. The Miles Davis Quintet performed together until 1957 when it broke up due to Coltrane’s drug problems. Coltrane then joined Thelonius Monk’s orchestra, but legal disputes interfered with the production of their recordings. In January 1958, he returned to Davis’s band, producing several recordings until April 1960. Later that year, Coltrane established his own band, with which he performed until his death in 1967. Although he was already active before 1955, he exerted the largest influence in the period between 1955 and 1967, when he gave modern jazz a new form, thus affecting generations of musicians. He was exceptionally productive during those twelve years: he led an orchestra in almost fifty recordings and contributed to many more. He created his legacy by venturing into increasingly spiritual domains. In 1960, he recorded My Favorite Things, which enjoyed immense success and also served as his debut as soprano saxophonist. According to some accounts, he received the instrument, which had not been used in jazz frequently, from Davis. Coltrane’s interest in the instrument was elevated by his admiration towards Sidney Bechet and Steve Lacy and by his interest in achieving higher pitch. As Coltrane’s style developed, he intended every performance to be a “complete expression of his self”, as he put it in an interview from 1966. Around that time, critics’ opinion shifted, so Coltrane also transformed his style. This surprised his audience to the extent that he was booed off stage on his last tour with Davis in France. In 1961, an article in Down Beat magazine accused him of playing “anti-jazz”. The most sold album of the classic quartet, Love Supreme, was recorded in December 1964. The album is the crown jewel of his oeuvre and is also considered an ode about his faith and love towards God. Coltrane’s subsequent compositions were determined by the same spirituality, as evidenced by the titles: Ascension, Om, and Meditations. The fourth part of Love Supreme is titled “Psalm”, which is the musical equivalent of Coltrane’s poem to God, printed on the inside cover of the album.

Figure 17: John Coltrane

Naturally, this study does not attempt to present every jazz saxophonist’s biography from the 20th century; it includes but is not limited to certain moments of the most influential musicians’ lives. Before presenting the legendary Michael Brecker’s career, who passed away recently, I now list some great jazz saxophonists (albeit I do not write about them in detail), without whom the history of 20th century jazz would not be as rich as it is. The list goes as follows: Benny Carter (1907–2003), Ben Webster (1909–1973), Art Pepper (1925–1982), Paul Desmond (1924–1977), Cannonball (Julian) Adderley (1928–1975), Stan Getz (1927–1991), Dexter Gordon (1923–1990), Walter Theodore „Sonny“ Rollins (1930–), Eric Dolphy (1928–1964), Phil Woods (1931–2015), Joshua Redman (1969–), Joe Lovano (1952–), Branford Marsalis (1960–), David Sanborn (1945–), Eric Marienthal (1957–), and Jan Garbarek (1947–).

Finally, Michael Brecker (1949–2007) must be mentioned, who was one of the most distinguished jazz saxophonists and composers of the 20th century (Figure 18). Despite his early death, he won 15(!) Grammy Awards during his career.

He was born in Philadelphia and raised in Cheltenham. His father was an attorney, who played the piano excellently and also improvised jazz; his mother was a portrait painter. Between 1975 and 1982, he played the tenor saxophone in the band called Brecker Brothers, which his brother, the outstanding jazz trombonist Randy Brecker, had established. Later he moved to New York and played in various bands. In the 1980s, he became the permanent tenor saxophonist for the Saturday Night Live Band.

Figure 18: Michael Brecker

During his career of more than three and a half decades, he collaborated with the most famous jazz musicians, such as Herbie Hancock, Pat Metheny, Charles Mingus, John Abercrombie, and with renowned rock musicians, such as Eric Clapton, John Lennon, James Taylor, Paul Simon, and Joni Mitchell. Many consider Brecker to have been the most original player with the most astonishing technique after John Coltrane. He combined his perfect technical skill with the force of musical expression. It is rare that a performer should possess both to such an extent.

The Origins of the French and American Schools of Classical Saxophone Performance

After its invention in 1840, the saxophone did not enter classical orchestras immediately. Many composers regarded it with doubt and scepticism. Some critics had a problem with its tone, but mostly it was unpopular because it was highly difficult to produce the exact pitch on it, which hindered its inclusion into most orchestras. It became frequent only in wind orchestras of Western Europe and the United States (Figure 19, John Philip Sousa Band).

Figure 19: John Philip Sousa Band, 1907.

The saxophone was not employed in Eastern European wind orchestras, possibly due to strong musical traditions. The acceptance of the instrument was also held up by the Soviet influence in the region after the Second World War, due to which the saxophone turned into an “unwanted instrument” and an emblem of “imperialist corruption” as it had become quite popular by then in the United States, the homeland of jazz.

In fact, it is mostly due to the saxophone schools of two countries and their outstanding talents that classical saxophone music has become famous worldwide and is now present in virtually all countries. As the title of the chapter suggests, the French and American saxophone schools are about to be discussed, with special regard to their greatest figures: Marcel Mule, French saxophonist, and Sigurd Rascher, a German-born American saxophone artist and instructor.

It goes without saying that there are various other distinguished saxophonists who contributed to the development of the instrument and the expansion of its repertoire. First, Belgian saxophonist Henri Wuille (1822–1871) must be mentioned, who, arguably, was the first soloist of the saxophone and popularised the instrument on multiple tours in England and the United States.

Another illustrious player, French clarinet and saxophone artist Louis-Adolphe Mayeur (1837–1894), learned to play the saxophone at the Conservatoire de Paris from Adolphe Sax himself. Mayeur was saxophonist for the Paris Opera and also an instructor. He published a saxophone primer titled Grande Méthode.

In a similar way to Henri Wuille, Edouard Lefèbre (1834–1911) also popularised the saxophone in the United States, for about twenty years between 1870 and 1890. For another nearly twenty years after 1890, he was saxophonist for the Patrick Gilmore Band and later for the John Philip Sousa Band (Figure 9), where he was thought to be the most outstanding player. Without Elise Hall (1853–1924), several pieces for the saxophone would not exist. She was a patron of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and started to play the saxophone as a child on her doctors’ advice due to her asthma. She commissioned one of the most famous works in the repertoire of the classical saxophone: a concert by Claude Debussy.

The history of the saxophone was also enriched by Rudy Wiedoeft (1893–1940), who produced numerous albums and adaptations and composed several pieces for the instrument. French saxophonist François Combelle (1880–1953) was solo saxophonist for the French Republican Guard Band, founded by Napoleon, and he also influenced Marcel Mule.

Two further people need to mentioned in the list of those who contributed to the prevalence of classical saxophone music: Cecil Leeson and Larry Teal. Cecil Leeson (1902–1989) was born and lived in the United States, taught at Northwestern University between 1955 and 1961 and at Ball State University between 1961 and 1977. Several American composers (including Paul Creston, Lawson Lunde, and Burnet Tuthill) dedicated compositions to him. Laurence (Larry) Teal (1905–1984) was the first to teach classical saxophone at the University of Michigan between 1953 and 1974. His textbook titled The Art of Saxophone Playing is to this day one of the most useful sources for saxophone instructors, artists, and students. The book includes useful methodological information on various topics such as the correct breathing technique, posture, and vibrato technique.

Marcel Mule, the Founder of the French Saxophone School

Marcel Mule was born in Aube, Normandy on 24 June 1901 and became familiar with the saxophone at seven. His father was a bookkeeper, who also played the instrument as an amateur musician. Besides the saxophone, Mule (Figure 20) also learned to play the piano and the violin quite well. At 20, he went to Paris to serve in the band of the Fifth Infantry. The musical environment in Paris made a profound impression on the young Marcel Mule. The fact that he had the opportunity to meet and listen to various influential saxophonists was decisive for his saxophone play and development. In 1923, he was admitted into La Musique de la Garde Républicaine as a principal saxophonist, where he worked for 13 years. In 1928, he founded a saxophone quartet with his colleagues, which at first bore the name of the Guard but later became famous worldwide as the Marcel Mule Saxophone Quartet. The band performed for approximately forty years, during which Marcel Mule was soprano saxophonist invariably. While Mule remained the leader and soprano saxophonist for the band for those years, few changes occurred in personnel.

Figure 20: Marcel Mule

Mule performed in and with several other orchestras, which culminated in 1936, when he had no choice but to leave the regiment by quitting as principal saxophonist for the Republican Guard. In subsequent years, he gave solo and chamber performances, which was appreciated in 1942 by an appointment as classical saxophone professor at the Conservatoire de Paris (Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris). He was the second appointed professor of saxophone at the institution, since saxophone instruction was discontinued at the Conservatoire with Adolphe Sax’s departed in 1870. Mule taught there until his retirement in 1968. Numerous composers dedicated works to him, and he also composed himself several methodological etudes and adaptations, thus contributing to the development of the repertoire for the saxophone.

“His success as a teacher was to match his achievements on the concert stage. During his twenty-six year tenure at the Conservatory, no fewer than eighty-seven of his pupils attained the first prize. But even the many first prizes do not convey the true measure of Mule’s influence on his pupils. His profound kindness, dedication, and wisdom as a teacher inspired his pupils personally as well as musically.“ (Eugene Rousseau, 1982)

Many of Marcel Mule’s students became notable figures of classical saxophone music in the 20th century, including Frederick Hemke, Jean- Marie Londeix, Eugene Rousseau, Daniel Deffayet, Serge Bichon, and Guy Lacour. Mule also contributed to saxophone pedagogy, and several pieces were dedicated to him, which are listed in the following.

Primers and collections of compositions by Marcel Mule:

- 24 Easy Studies for All Saxophones after A. Samie, Leduc. Alphonse Leduc, 1946

- 30 Great Exercises or Studies (Trente Grands Exercices ou Études) for All Saxophones after Soussmann Book 1 and 2 by Marcel Mule. Alphonse Leduc, 1944

- 48 Studies by Ferling for All Saxophones by Marcel Mule. Alphonse Leduc, 1946

- 53 Studies for All Saxophones Book 1, 2 and 3 by Marcel Mule. Alphonse Leduc, 1946

- Daily Exercises (Exercices Journaliers) for All Saxophones after Terschak by Marcel Mule. Alphonse Leduc, 1944

- Scales and Arpeggios, Fundamental Exercises for the Saxophone Book 1, 2 and 3 by Marcel Mule. Alphonse Leduc, 1948

- Varied Studies (Études Variées) in All Keys adapted by Marcel Mule. Alphonse Leduc, 1950

- 18 Exercices ou Études d'après Berbiguier, by M. Mule, Leduc

Works dedicated to Marcel Mule:

- Roger Boutry: Divertimento, 1964

- René Corniot: Eglouge et danse Pastorale, 1946

- Fernande Decruck: Sonate en Do, 1944

- Alfred Desenclos: Prélude, Cadence et Final, 1956

- Paul Bonneau: Caprice en forme de valse, 1950

- Jean Francaix: Danses Exotiques, 1962

- Henri Tomasi: Concerto, 1949

- Heitor Villa-Lobos: Fantasia Op. 630., 1948

Sigurd Rascher, the Founder of the American Saxophone School

Sigurd Rascher was born on 15 May 1907 in Elberfeld, Germany (now part of Wuppertal). He studied clarinet and graduated as a clarinet artist from the Stuttgart Musikhochschule in 1930. It was in the same year when he first encountered the saxophone. He gave saxophone concerts as early as 1932. Political transformations in Germany (Hitler’s power grab with the far right) forced him to leave his homeland in 1934, and he began to teach classical saxophone at the Royal Danish Conservatory in Copenhagen. Later he moved to Sweden to teach at the Malmö Conservatory. In 1939, he relocated to the United States, where he was in demand by the most renowned symphonic orchestras. Among others, he performed with the Boston Symphony Orchestra (20 October 1939, conductor: Serge Koussevitzky), the New York Philharmonic Orchestra (11 November 1939, conductor: Sir John Barbirolli), the Philadelphia Orchestra, and the Cleveland Orchestra. Rascher’s performances inspired various composers, who dedicated works to him (Alexander Glazunov, Darius Milhaud, Jaques Ibert, Lars Eric Larsson, Frank Martin). He mastered the so-called altissimo register, resulting in a range of four octaves on the instrument. The technique, now prevalent in modern saxophone music, has created new perspectives for composers.

Figure 21: Sigurd Rascher

He founded the Rascher Saxophone Quartet in 1969 with his daughter, Carina Rascher, Linda Bangs, and Bruce Weinberger. The ensemble is still one of the most illustrious saxophone quartets in the world, despite the inevitable changes in personnel. The quartet has performed in every European country as well as in the United States, Mexico, Canada, South East Asia, and Australia. After a concert in Vienna, the Wiener Zeitung praised the quartet as “Uncrowned Kings of the Saxophone”. Almost 300(!) works by composers from over 35 countries have been dedicated to the quartet, including pieces by renowned composers such as Luciano Berio, Philip Glass, Iannis Xenakis, Sofia Gubaidulina, Miklós Maros, and Mauricio Kagel.

Rascher strived on transferring the knowledge he had acquired and teaching young people, so he continued his work as a teacher, which he began in Europe, also in the United States. He taught at four leading institutions: at the Juilliard School, the Manhattan School of Music, the University of Michigan, and the Eastman School of Music.

The list of works composed for and dedicated to Sigurd Rascher include:

- Alexander Glazunov: Concerto pour Saxophone Alto avec l'Orchestre de Cordes in Eb Major, op. 109., 1934

- Paul Hindemith: Konzertstück für Zwei Altsaxophone, 1933

- Jacques Ibert: Concertino da camera pour saxophone alto et onze instruments, 1935

- Lars Erik Larsson: Konsert för Saxophon och Stråkorkester, 1934

- Frank Martin: Ballade for Alto Saxophone, String Orchestra, Piano and Tympani, 1938

Similarities and Differences between Classical and Jazz Saxophone Music

I have arrived at the section of the study which carries the title of the whole. The topic is an aspect of saxophone music which has been at the centre of my interest and fascination from the beginning. Previous chapters have informed the readers about the invention of the saxophone family by Adolphe Sax and its circumstances, have explored the origins of jazz, and have introduced several distinguished jazz and classical saxophonists’ life and career. While previous chapters could have been interesting and exciting for anyone, the section to come will be directed primarily at saxophonists and at musicians who play other woodwind instruments.

The two styles display various differences. First, the selection of instruments is not the same; second, classical and jazz saxophonists use different mouthpieces and reeds. The two largest differences, however, lie in sound production (embouchure) and in replicability: in the classical style, musicians “reproduce” composers’ works, whereas jazz saxophonists improvise, that is to say, they “invent” the sounds they play during the concert, as they go along. Now let us discuss certain differences in detail.

The Instrument, Mouthpiece, and Reed

An apparent similarity between jazz and classical saxophone music is that the sound is produced in both cases using the saxophone, the mouthpiece, and the reed. However, certain differences also arise in this regard. Classical saxophonists prefer recent instruments, with a rapidly (if not annually) developing mechanical structure, since leading saxophone manufacturers around the world invest heavily in constant development. Major saxophone makers employ prominent saxophonists to be part of the design and testing of new instruments and to assist the creation and development of certain versions. Usually (at least at the Selmer company), a group of 3–4 saxophonists each participate in the development of jazz and classical saxophones. Often the saxophonists involved play different instruments, that is to say, they are specialists of the soprano, alto, tenor, or baritone saxophone. To reiterate, saxophonists in the classical genre prefer the most recent and current models, while jazz saxophonists favour relatively old instruments, mainly because they are convinced that the wear in the lacquer (or the lack thereof) results in a richer and louder sound, which is a valid requirement if the instrument is to be heard alongside a complete jazz orchestra or a big band. Although jazz and popular music saxophonists utilise amplifiers, which makes the original volume irrelevant, they still prefer old instruments with the lacquer worn off to new ones, despite the relative difficulty of executing certain technical solutions and potential problems of intonation on old saxophone models. The most popular model among jazz saxophonists has been the Mark VI produced by the Selmer company between 1954 and 1981, which is considered by some the best saxophone ever made. Just as there are certain car models which happen to stand out in form, reliability, build, etc. and are widely favoured as a consequence, musicians also swear by specific instruments. The above-mentioned instrument, which was designed in the 1950s as a high-end model and has been the favourite of many jazz and classical saxophonists, provides a great example: it is still regarded as the zenith of saxophone production by certain classical saxophonists and predominantly by several jazz saxophonists, despite the influx of more recent models in the past 60 years and the mechanically outdated build of the model.

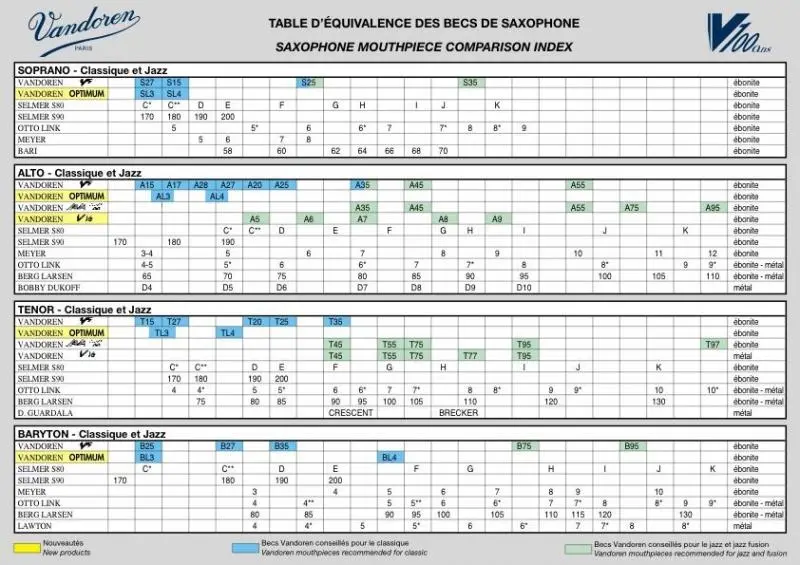

The next significant difference lies in the mouthpiece, which determines the quality and nature of the produced sound. Classical mouthpieces are made usually of hard rubber or plastic (Bakelite) and sometimes of glass, whereas saxophonists who play jazz or popular music often use metal mouthpieces as well as hard rubber ones. As opposed to classical saxophonists, who look for a uniform sound in all registers and select the mouthpiece and the reed accordingly, jazz saxophonists consider it less important to produce similar sounds in both lower and upper registers. Instead, they seek to make a rich and loud sound with their instrument-mouthpiece-reed combination of choice. To assist the decision about the adequate mouthpiece, manufacturers publish mouthpiece comparison tables (see Figure 22), which offer a clear overview on mouthpieces for both classical and jazz saxophonists.

Figure 22: Saxophone mouthpiece comparison table

It is relatively complicated to answer the question as to which mouthpieces are satisfactory. First, manufacturers develop and market new mouthpieces constantly. Second, differences in sound can arise even among instances of a given type of mouthpiece, since two entirely similar mouthpieces do not exist. Third, the choice of mouthpiece is largely dependent on the style of music to be played as well as on the artist’s experience, in particular, whether the user is a professional or merely a student at the secondary or tertiary level. Of course, this does not mean that the choice of mouthpiece for beginners or students is unimportant; quite the contrary is true. Nevertheless, the general rule applies that the care required for selecting the adequate mouthpiece should increase with the level of technical and educational proficiency. This is where complications arise. Each individual has a different “mouth structure” and volume requirement. For beginners, popular (standard) mouthpieces and reeds are advised, but the final goal is that the student should arrive at a personal preference which is the most appropriate and fitting for the desired style and sound. In other words, the choice of mouthpiece depends on the player’s physical form (lips, teeth, oral cavity, tongue), the embouchure (the technique of playing the saxophone, which will be discussed in detail below), and the style to be played (classical, jazz, pop, dance music, folk music, etc.). The most crucial aspect is that players should be able to handle the mouthpiece and the instrument in the easiest possible way with respect to the style they play. In addition, the mouthpiece should assist the execution of musical ideas and technical elements in an optimal way.

After having discussed classical and jazz saxophonists’ preferences over instruments and mouthpieces, a most important factor needs to be explored still, namely the reed, without which saxophones could not be sounded. The reed is essential for the production of sound on the instrument because it creates the vibration which is later amplified by the mouthpiece, the oral cavity, and, finally, the body of the instrument, eventually producing the sound. According to the generally held belief, the tone of the produced sound is determined primarily by the ideal combination of the oral cavity, the mouthpiece, and the reed, while the contribution of the instrument itself is almost insignificant(!). Needless to say, such a statement is somewhat exaggerated, as major differences may exist between different saxophone models, but it is still true that the tone is largely influenced by the combination of the oral cavity, the mouthpiece, and the reed. The contribution of the instrument lies in the facilitation of intonation and the simplicity of executing technical components, which is dictated by the build and design of the saxophone. The musicians’ (saxophonists’) hearing, that is, musical perception is also an important factor as it constitutes a determinant of the sound, alongside the already listed items. This is because hearing shapes the intention about the exact tone to be produced as well as the perception of perfection and beauty.

The available variety of reeds is even greater than it is the case with mouthpieces. Reed manufacturers produce reeds of varying type, strength, and cut. There are even designs specifically developed for classical or jazz saxophonists. It is every player’s responsibility and goal to find the mouthpiece-reed combination which corresponds to the musical taste and style and enables the performance of music as intended. Classical and jazz saxophonists favour mostly the products of the French Vandoren and the American D’Addario (formerly Rico) companies, to mention the two largest. Reeds are also produced by various smaller manufacturers (Silverstein, Glotin, La Voz, Steuer, Selmer, etc.). In the past 15–20 years, several reed makers have experimented with manufacturing plastic reeds. About 8–10 years ago, the Légère company managed to design a plastic reed which has been widely used by classical saxophonists as it is reliable and, depending on the intensity of use, lasts up to two years. The advantage of the plastic reed over the traditional one lies in its durability and resistance against changes in weather and moisture. However, it has the disadvantage that it gradually loses its strength during use (which recovers subsequently) and, consequently, produces lower volume in forte than its traditional counterparts.

Differences in Classical and Jazz Embouchure (Ansatz)

In musical terminology, the correct position of the mouth when sounding the instrument is called embouchure (Ansatz in German). The ideal embouchure for classical saxophonists is stable and regular. This means that (optimally) the two central incisors are placed directly above the mouthpiece, while the lower lip is in a turned position below the reed, which is connected to the mouthpiece. The jaw is slightly “stretched” downwards. The ideal embouchure resembles whistling. The mouth forms an “o” or “u” sound, with the jaw “stretched” downwards somewhat. The word “stretched” is in parentheses because embouchure should not be tense at all; it is only used to illustrate that the chin must not be “bunched” under the mouthpiece with classical embouchure. It is important to note that the mouthpiece rests on the lower lip with the classical embouchure, as opposed to the jazz embouchure, whereby the weight is centred at the upper central incisors and the jaw is not required to be in a stable position. As explained previously, uniform sound is a necessity in classical saxophone music; that is to say, the saxophone should produce the same tone in all registers. In jazz, there is no such requirement. Jazz saxophonists often produce lower notes using the so-called subtone technique, whereby they limit the vibration of the reed with their lower lip, resulting in an interesting, clattering, muted sound on the instrument.

Afterword

I sincerely hope that this study has provided the readers with a broad overview about the saxophone as well as the similarities and differences between classical and jazz saxophone music. Needless to say, I have not attempted to offer a comprehensive analysis; I have only ventured to draw attention to the topic. For reasons of space, the study has not explored all major differences between classical and jazz styles, most notably the performance of composed musical material for the classical style as opposed to improvisation in jazz. In classical music, not only when the saxophone is played but generally, the musician performs a piece by the composer as it is notated in the sheet music. By contrast, jazz merges the player and the composer, since jazz musicians play by combining previously practised patterns in an order as they please, resulting in improvisation. Hopefully, this study has been sufficiently informative even though it has not delved into differences in performance.

References

- Berlioz, Hector (1953): Treatise upon Modern Instrumentation and Orchestration (Paris 1848). Transl. Mary Cowden Clarke. London.

- Dauer, Alfons M. (1961): Jazz, die magische Music. Carl Schünemann Verlag, Bremen.

- Hemke, Frederick (1975): The Early History of the Saxophone, University of Wisconsin.

- Ingham, Richard (1998): Saxophone. Cambridge University Press.

- Pernye András (1964): A jazz [The Jazz]. Gondolat Kiadó, Budapest.

- Rousseau, Eugene (1982): Marcel Mule: His Life and the Saxophone. Shell Lake.

[1] Here, and in the following, subscripts correspond to the International Pitch Notation (the translator).