Author: Csaba Zoltán Nagy

DOI: 10.5434/9789634902263/8

Abstract

In the past few decades there have been major changes to historically informed performance practice. Early music departments have appeared in conservatories worldwide, where one can study early music on period instruments according to extant performance sources. Despite historically informed performance practice being well-known and well-acknowledged, no course has been offered thus far by Hungarian conservatories, resulting in the phenomena of young professionals with bachelor and/or master degrees but with only scarce awareness of this practice. This essay provides readers with the basic notions of early music performance, emphasizing the particular mentality shaping its theoretical foundation.

Keywords: early music, historical performance, early music department

Introduction

The hopeful title in fact refers to decades worth of shortcomings and deficiencies: in Hungary today, higher education institutions do not offer training in early music. Consequently, students graduate with little knowledge on historical performance, which is common, recognised, and influential throughout the world. What they do know comes from elective courses on early music and individual research.

A few years ago, I was talking with a recently graduated fellow teacher, and early music came up. At the beginning of the conversation, she confidently reported that the performance of Baroque music in her field (instrument) was doing as great as ever because of the unbroken performance tradition. Soon it turned out that the “unbroken tradition” could be traced back to her instructor’s instructor. She ended the conversation with a shocking sentence: “How come I never heard about any of this [of what I had told her] during my studies?”

Now, followers of historical performance are not cast out anymore as “heretics”, but it is still a long way away until early music receives the place it deserves in music education. I regularly hear remarks even from professional musicians and music instructors which make it clear that the individual has little idea of the subject but still does not refrain from forming a harsh judgement, which is mostly belittling and derogative.

The term “early music” is mostly used to refer to the music of the Baroque era or even earlier periods. In another sense, which was in use in the 17th and 18th centuries, it can indicate anything which has been premiered. Importantly, I refer to Baroque music exclusively when I mention early music in this study.

In this study, I wish to point out the fundamental questions of early music performance and the way towards a “new understanding of music”, in Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s words (1988).

Why is the Performance of Early Music Ambiguous?

In the past decades, I have had the impression that there are only vague ideas and presumptions even among professionals about the origins of and reasons for the novel interpretation of early music, which have led to misunderstandings and prejudices.

Therefore, the first question to be asked in relation to early music performance is this: why is the performance of early music ambiguous?

It is natural for us to select in the musical scene among musical pieces from different centuries. Audiences today can encounter compositions by Monteverdi (or even earlier composers) as well as by Brahms, Bartók, or Levente Gyöngyösi. We might think that this has always been the case, that is to say, both contemporary and historical pieces have always been performed.

However, documents from the history of music reveal that mostly contemporary music was played up until the 19th century. Contemporary music was intended to address the moment in the moment. Harnoncourt explains this as follows: “Today, historical music, particularly music of the 19th century, forms the basis of musical life. Since the rise of polyphony, such a thing has never happened” (Harnoncourt, 1988, p.10). The same is described by Jos van Immerseel in an interview: “Before, people played music for the moment […] and performed contemporary pieces only. Every piece of music was new music” (Péteri, 1987, p.12).

The desire for novelty was so great in Italy that compositions were often performed only once and sheet music was not worth publishing, because by the time it reached the press, nobody was interested in it anymore.

For a contemporary music enthusiast, it is unthinkable what Harnoncourt describes: the renowned Romantic violinist Joseph Joachim discovered a “musical jewel” in the library but wrote to Clara Schumann that “of course something like this could no longer be performed in public”. The discovered piece was Mozart's Sinfonia Concertante for violin and viola (Harnoncourt, 1988, p.137).

When pieces from earlier periods were performed in the late 18th century or in the 19th century, they were altered according to current tastes.

It is known that Mozart premiered several of Händel’s works at the request of Baron Gottfried van Swieten (Acis and Galatea, 1788; Messiah, 1789; Ode for St. Cecilia’s Day, Alexander’s Feast, 1790).

Mozart did not just lead the performance of these pieces; he also altered them according to the taste of the period. For example, the score of Messiah was appended with flutes, clarinets, horns, trombones, while the timpani got an enhanced role. (Mozart’s version of the Messiah was broadcast by the Hungarian Radio a few years ago.)

In 1829, Mendelssohn presented the St. Matthew Passion by Bach. It was reported at the time that the performance corresponded to Bach’s ideas entirely, which is unusual because Mendelssohn modified Bach’s score substantially.

As member of the Orfeo orchestra, I have had the opportunity to perform the St. Matthew Passion in both the original version and Mendelssohn’s transcription, thus experiencing the differences first-hand. (Mendelssohn employed lower-pitched string instrument instead of the harpsichord in recitatives, modified the orchestration, left out movements, and shortened some sections.)

In the early 20th century, when musical interest began to turn towards the Baroque, musicians faced two problems. First, there was no unbroken authentic tradition on which early music performance could have been based; second, the Baroque interpretation they inherited had nothing to do with actual Baroque performance practice.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when concert repertoire contained few pieces from earlier periods, the question of interpreting compositions of various styles in the appropriate manner was not addressed. As Harnoncourt puts it: “basically one style of interpretation has been used for the performance of everything from the early Baroque to the late Romantic: a style that was designed for and is excellently suited to the music of the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, for Tchaikovsky, Richard Strauss and Stravinsky” (Harnoncourt, 1988, p.134).

As the proportion of early music grew, there was an increasing number of performers who were disturbed by the “intolerable gulf”, in Harnoncourt’s words, between the works and the way of interpretation (Harnoncourt, 1988, p.134).

The situation resulted in three directions for the performance of Baroque music, which are still present in the musical scene.

1. Early music has been mostly performed according to the musical taste of the 19th-century late Romantic period. This is usually referred to as “traditional” performance practice, which, however, is not based on the Baroque tradition. Although it seeks reference to the Baroque heritage, this is not justified from the perspective of music history.

I wish to illustrate the above with an example. As a recently graduated instructor, I asked my students, who were preparing for a performance, whether they had heard of the rule that the trill for descending notes was to be initiated from the upper auxiliary note. I then explained that the “rule” first appeared in 1872, in the book titled Musical Ornamentation by the renowned musicologist Edward Dannreuther. (For the record, the literature puts the end of the Baroque period at around 1750…) In a 1933 lecture, János Hammerschlag refuted Dannreuther’s claim and expressed his regret over the practice of forcing inadequate ornaments to Bach’s works in certain editions. Hammerschlag also warned in 1952 that the mistakes remained in later editions, as well (Szabolcsi and Bartha, 1953).

This topic was widely discussed among 17th-century theoreticians, including Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg, whose treatise reads as follows:

“A trill, wherever it may stand, must begin with its auxiliary note […] If the upper note with which a trill ought to begin immediately precedes the note to be trilled, it has either to be renewed by an ordinary attack, or has, before one starts trilling, to be connected, without a new attach, by means of a tie, to the previous note”. (Donington, 1978, p.193)

The list of misguided instructions is easy to continue: “in the Baroque period, crescendo was not known,” said one of our lecturers a long time ago. “in the Baroque period, staccato was not known,” I heard in another lecture. When we asked about the differences between regional styles (for example, between the French and German styles), we were told not to overcomplicate things as the Baroque had one sole style. I could also mention the example of a young musician who performed a Händel movement with ornamentation in the repetition, which was condemned by the judges, who argued that no ornamentation could be allowed because it was not known how embellishments had been used at that time. When during a session I started a trill with a relatively long and accented upper auxiliary note, my instructor told me that this was not natural and adequate. However, treatises from the period are practically in concert that trills should be initiated from a long and accented upper auxiliary note, with a few notable exceptions.

The approach, which was imported from the Romantic period without any critique or consideration, also influenced other fields. About the categorisation of Bach’s works for keyboard instruments (to determine which piece was intended for which instrument), András Pernye writes the following:

“As we have read: the organ-piano distinction first appeared in Johann Nikolaus Forkel’s book about Bach […] which distinction has been mostly kept until today. This, however, is not more than some form of common law, preserving a process which originated in the Romantic period. We must categorically reject that a custom which appeared half a century after J. S. Bach’s death should be interpreted as the practice from Bach’s period and the only possible performance style. This is a mere falsification of history”. (Pernye, 1981, p.251)

2. In the early 20th century, another way of performing early music emerged, which can be traced back to the societal transformations of the era. An opposition emerged against the existing society and forms of cultural expression, which were considered untrue by many. Contemporary music was deemed as untrue and redundant as the society these people rejected. Earlier periods were idealised, which lead them to the music between the 16th and 18th centuries, where the desired purity was found.

This is how the “anti-Romantic” performance and style emerged, according to which compositions are to be performed in an objective manner, as opposed to the subjective Romantic approach. The largest mistake of the initiative lied in the fact that it read and interpreted scores of early music according to the late Romantic practice, which it wished to terminate. Harnoncourt also explains this:

“But the real misunderstanding occurred in the first half of our own century, in connection with the vogue of so-called faithfulness to the work: older scores were "purified" of 19th-Century additions and performed in a desiccated form. Yet the principle of the 19th Century in which what the composer intended had to be found expressly in the notes was retained and vice versa: anything not found in the notes was not intended and represented an arbitrary distortion of the work”. (Harnoncourt, 1988, p.37)

As Harnoncourt (1988) remarks, the idea is flawed because it originated in the 19th century and was not present in the Baroque (Classical) era.

3. The third possible way to perform early music is to rely on sources from the period while attempting to perform scores in accordance with the performance practice of the Baroque era. This is called “historical” performance. It is important to see that historical performance is not the result of some romantic admiration or archaising desire but that of recognising the incompatibility between early music and 19th-century performance style, which I have alluded to above.

Baroque Musicians’ Idea of Music and Its Purpose

To learn the Baroque practice of performance, it is not enough to memorise the rules: it is also vital to understand the idea of music and its role held by musicians of the period because the way of thinking is often reflected in concrete musical solutions.

Various books in the literature point out the decisive transformations in the musical scene in Italy at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries (Jeppesen, 1975; Harnoncourt, 2002; Szabolcsi, 1977; Darvas, 1977). What did the transformation involve? Based on treatises and documents from the period, it can be concluded that the answer lies in the relationship between words and music.

Between the emergence of polyphony and the 17th century, a large variety of musical rules were introduced. Dissonances were regulated especially strictly: they could not be employed anywhere, needed preparation, and could not be inserted suddenly.

The melodic structure was also restrained. Achieving a flawless counterpoint was among the strictest requirements, demanding significant knowledge. Perfection in form was an important indicator of composers’ professional qualification.

In the early 17th century, an increasing number of composers and theoreticians, who played an important role in the musical scene, argued that rules limit the effective expression of emotions and feelings in the text. In Giuliano Caccini’s (1551-1618) words: “the old contrapuntal way of composition results in the death of poetry because words in such music are not understandable” (Barna, 1977, p.107).

In European culture, music had been mostly vocal. According to Carl Dahlhaus, “language was a regular component of music until the 18th century” (Dahlhaus and Eggebrecht, 2004, pp.41-42), that is to say, words played an important role in music, but before the 17th century the structure of the poem was considered primarily and perfection in form was not sacrificed for emotional expression, as Claude Palisca notes (Palisca, 1976, p.23).

At the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries, a dramatic change occurred. Knud Jeppesen, renowned scholar of the Palestrina style, writes that the need for music to serve poetic expression emerged as early as the beginning of the 16th century, alongside obvious attempts towards expressing the emotions from words (Jeppesen, 1976).

In the early 17th century, members of the Camerata of Florence investigated ancient artists and concluded that dramas in Ancient Greece were sung to facilitate the understanding of words and enhance the emotional content in them.

The suggested solution was to “imitate speech with melody”, as explained by Jacopo Peri (1561-1633) in the foreword of Euridice, by setting aside any vocal style up to that point to better express poetry (Barna, 1977, p.103-104).

The solution included the following three things:

- the free use of dissonances,

- the replacement of polyphonic composition with chord-based notation,

- abandoning ecclesiastical keys.

In the foreword of “Le nouve musiche”, Giuliano Caccini argues for the primacy of the platonic definition of music, according to which “music is words and, thereafter only, rhythm and sound, and not the reverse” (Plato, 1989, p.113). What follows is the brief summary of the Baroque approach:

“I should attempt to convey music into people’s minds to arouse emotions which the writer wants to achieve” (Barna, 1977, p.108).

The composer wants to transfer listeners to a predefined emotional state. Thus the composer, as Dietrich Bartel suggests, controls and manages listeners’ emotional state as an orator, knows what emotions to evoke in the audience (for example, joy, happiness, sorrow, uncertainty, fear), and has the musical tools to achieve this (Bartel, 1997).

According to Jan Wilbers, Baroque composers did not write about their own subjective thoughts but wanted to transfer listeners to different emotional states. Music is intended to shake up and awe listeners (Wilbers, 1995).

Rhetoric: The Key to Baroque Music

As interest in the music of earlier periods grew, the discovery did not end with works by early composers and reached early theoreticians’ studies, which revealed practical information as well as the idea of music being words in notes, as pointed out by Andrew Wilson-Dicksohn (Wilson-Dickson, 1988). It followed that the same laws apply to music as to the art of oration, that is to say, rhetoric. Rhetorical thinking contributed to the composition, judgement, and performance of musical works. There were numerous connections between rhetoric and music. Examples for the influence of the rhetorical thinking include unexpected changes in harmony, unusual melodic turns, and even ornamentation.

The importance of speech was also evidenced by noticeable characteristics. Reinhold Kubik highlights that the melody in cadences often descends irrespective of the meaning of the words, which resembles the intonation of human speech (Kubik and Lehrer, 2009).

To better understand the music of the period, it is not enough to analyse works from the perspective of form theory and harmony theory, but rhetorical thinking should be internalised again, which is essential for understanding and performing music from the period. According to Jan Wilbers, rhetoric is the key to the music of the era (Wilbers, 1995). Brus Hayns suggests the term “rhetorical music” instead of “early music” (Hayns, 2007).

Although rhetoric was an integral part of education in the 17th and 18th centuries and was decisive in musical thinking at the time, current music education hardly mentions it in relation to Baroque music.

Due to the importance of the topic, I explore in detail the relationship between rhetoric and music and the practical significance of rhetorical knowledge.

The Relationship between Rhetoric and Music

Initially, music and rhetoric, the art of oration, were separate. The intimate relationship between the two art forms is evident from Joachim Quantz’s (1697-1773) description: “Musical execution may be compared with the delivery of an orator. The orator and the musician have, at bottom, the same aim in regard to both the preparation and the final execution of their productions, namely to make themselves masters of the hearts of their listeners, to arouse or still their passions, and to transport them now to this sentiment, now to that” (Quantz, 2011, p.23).

Besides theoretical similarities, the relationship has several practical aspects.

The most noticeable is the structure of a prepared speech and a piece of music. Rhetoric distinguishes between three divisions of oratory: forensic, political, and ceremonial. In a similar fashion, music also has a three-way division: church, stage, and chamber music. Both are temporal in nature, comprise the changes of their components, and require sound because both appear in performance.

In rhetoric, poetry, and music, an important role is designated to repetition, pauses, and contrasts. Hans-Heinrich Unger relates this to a common physiological ground, namely that taking breath is necessary for both speaking and singing. The significance of mentioning the necessity of breathing lies in Unger’s argument about pauses having been elevated to a higher sphere and having become rhetorical devices (Unger, 1941, p.18).

The situation of repetitions is similar. Repeating sections of varying duration is a fundamental device in both art forms. The decisive role of repetitions, irrespective of musical style, is also underscored by Arnold Schönberg: “Intelligibility in music seems to be impossible without repetition” (Schönberg, 1971, p.37).

The manner of dividing musical compositions, speeches, or other literary works is also similar. A speech or literary work is as incomprehensible without commas and full stops as music is without harmonic and melodic rests. This is clearly evidenced by recitatives, where melody and words share the same divisions.

Other points of similarities include dynamics, changes in metre, and rhythm, which are indispensable in both music and speech. Hans-Heinrich Unger quotes Otto Behagel in pointing out another similarity, namely the law of growth and development, according to which “the second of two parts is usually more” (Unger, 1941, p.19).

Tamás Adamik is among those who underline the following similarity between music and rhetoric: both need to be understandable with logically structured thoughts because both attempt to affect and direct the emotional state of the audience (Adamik, Jászó, and Aczél, 2004).

Johann Mattheson relates understandability with proper melodic composition, which he describes extensively in his book titled Kern melodischer Wissenschafft by calling melodic composition the most intimate essence of music. As a result, the importance of understandability in melodic composition is even more pronounced (Barna, 1977, pp.150-158). The principles of proper melodic composition are detailed in Chapter 5 of Section 2 of Vollkommener Cappelmeister, published two years later. The most important aspects include the objective of naturality, the preference of small steps over large ones, and the avoidance of a long melody (Mattheson, 1999, p.219).

It is also worth mentioning that Baroque theoreticians’ parallels between music and rhetoric contained references which were universally known among educated people at the time. In the 17th and 18th centuries, rhetoric was an integral part of education. Its significance is evidenced by the fact that in German-speaking regions, as Ernő Imre reports, “440 books about rhetoric were published between 1600 and 1700” (Imre, 2003, p.434). Rhetorical utterances were easy to encounter in everyday life. As Árpád Vígh puts it: “rhetoric influenced every walk of life” (Vígh, 1981, p.354). This was especially true for the church, where sermons during services followed strict rhetorical principles in their structure.

The significance of rhetoric in the musical scene is evidenced not just by treatises but also by various anecdotes. I describe here a series of letters from the mid-18th century. The correspondence is discussed in detail by Romein Rolland (Rolland, 1960, pp.104-110).

A composer and theoretician of the period, Carl Heinrich Graun (1704-1759), criticised Jean-Philippe Rameau in a letter dated 9 November 1751 with regard to certain parts of the opera Vastor and Pollux. He analysed a recitative in Act II, Scene 5 and deemed it unnatural. Moreover, he questioned the composer’s expertise in rhetoric in a sarcastic way.

Telemann replied by stating that Rameau’s passages show “no little discernment in the art of diction” (Telemann, 1985, p.240). He then analysed the recitative himself, proving the opposite of what Carl Heinrich Graun had written.

Telemann was eager to mention that he also wanted music to resemble speech and demonstrated what he meant using the recitative. The letter reveals several details of rhetorical thinking, which could help performers today in sounding certain musical elements.

Telemann’s letter explains that the lower appoggiatura “softens the melody”. An ascending melody with a chromatic semitone step (pathopoeia) reminds Telemann of “pride”. As the melody jumps a quarter (exclamation), it is “elevated”.

One element of the correspondence seems at first to prove Graun right. The words of the bar in question, to which Rameau wrote a descending melody: “L’arracher au tombeau” (take out of the tomb). Graun used this sentence to point out that “put into the tomb” would have been a better choice, in reference to the negative emotional content of the descending melody. However, he might have missed the chromatically ascending motif in the bass, namely C–C-sharp–D–D-sharp (passus duriusculus), which has a more impactful positive effect than the descending melody.

The discussed details reveal that rhetorical devices should be investigated carefully and it is not advised to take one element out of its context. The composer’s intention is often reflected in the contrast between multiple devices. In other words, truly great composers employ rhetorical devices in a refined manner.

In his response, Telemann criticised that Graun’s proposal divided a logically cohesive section with a rest. This refers to the rhetorical role of pauses indirectly because rests have a musical and rhetorical significance, as well.

The discussed correspondence is similar to another one, which occurred 20 years before, as reported by Christoph Wolf. Adolf Scheibe found Johann Sebastian Bach’s rhetorical expertise insufficient in his music, in a similar way to Carl Heinrich Graun and Jean-Philippe Rameau. Just as Telemann proved Rameau’s right, Johann Birnbaum, lecturer of Latin and rhetoric at the university of Leipzig, used rhetorical arguments to prove that Johann Sebastian Bach’s music was not confused but rather the opposite: he was a master of his craft. (Wolf, 2009, p.XXX). Both correspondences show that referring to rhetoric in judging composers and their works was a decisive argument even at the end of the Baroque period.

Rhetorical Devices

In the art of oration (rhetoric), the orator can best affect the audience using extraordinary terms and phrases. These are often called rhetorical devices or figures. To provide a mundane example: if somebody says “Please give me a glass of water”, it is regarded as a calm, courteous, ordinary request. Presumably, nobody would jump from their seat to fetch water. Conversely, if the person says “Water, water, a glass of water!”, then we perceive that there is probably something going on and the water is extremely important. The second request contained two rhetorical devices:

- anaphora (repetition),

- and complexio (the sentence has the same beginning and ending).

To provide an example from literature: in the 13th century, King Edward I of England sent five hundred bards from Wales to their death as they refused to praise the invading tyrant. János Arany described this as follows:

„Ötszáz, bizony, dalolva ment

Lángsírba velszi bárd” (Arany, 1981. p.328)

“Five hundred went to a flaming grave,

And singing every bard” (English translation by Neville Masterman)

The poet changed the usual word order (which would be “ötszáz velszi bárd, bizony, dalolva ment lángsírba” in Hungarian or “all five hundred bards went to a flaming grave singing” in English), which is called hyperbaton. The equivalent for this in music is the continuation of the melody in another key.

To get into the minds of others and achieve a predetermined emotional state in the audience, the tools of conscious persuasion must also be exercised in music.

There is consensus among theoreticians of the time as well as 20th-century music historians and musicologists that conscious expression is the most tangible in rhetorical devices, which play a disproportionally large role in the materialisation of expression (Pintér, 2001; Péteri, 1987).

According to Dietrich Bartel, the relationship between rhetoric and music is materialised most frequently in the use of rhetorical figures (Bartel, 1997), which have the task to make the feelings in text understandable and distil the emotional weight of words. This can be achieved using unusual solutions in both oration and music. Examples include: prolonging a dissonance by slurring it over the beat (catachrese); not including the dissolution of a dissonant chord or including another dissonance in its place (ellipsis); augmented or diminished steps (saltus duriusculus); augmented or diminished chords (parrhesia); abruptly stopping the melody in various places (abruptio); or repeating a motif in several places (one after the other, at the end of the musical thought, or at the beginning of the next musical section) in various ways (from below, from above, diminuendo) (anaphora, analepsis, auxesis, epizeuxis).

Treatises on rhetoric distinguish about 150 devices. Hans-Heinrich Unger proposes four categories for rhetorical devices which are:

- only used in music (e.g., abruptio, catabasis),

- only used in oration (aetilogoia, hyphen),

- used in both and signify the same phenomenon (anadiplosis, exclamatio) (Unger, 1941. pp.64-66),

- somewhat similar in their meaning (epanalepsis, hyperbole).

When a device is present in both art forms, it is useful to read the original rhetorical definition. This is referred to by both theoreticians form the period and 20th-century musicologists (Bartel, 1997, p.171; Unger, 1941, p.77).

The musical composition is aided if not just the figure itself is identified but also the reason for it is known.

For example, repetition devices compel the orator to repeat words or phrases which are significant for the message. Repetition is a way to reinforce the message, which is not useless redundancy but rather the highlighting of what is significant.

It is worth mentioning that word repetitions in vocal pieces may often seem arbitrary. Listeners and performers today might have the impression that composers repeat words for the sole reason of not running out of text for the melody. Hartmut Krones points out, however, in quoting a 1697 study (Musikalisches Sommer-Gespräche) by Georg Ahle (1651-1706), Johann Sebastian Bach’s predecessor in Mühlhausen, that word repetitions in Baroque pieces were consciously composed according to rhetorical principles. Using the words of Psalm 98, Georg Ahle demonstrates various ways in which words can be altered to create rhetorical devices: “Jauchzet dem Herren alle Welt, singet, rühmet und lobet”. The orator uses words of gradually increasing intensity, which is called gradatio. If written this way: “Jauchzet, jauchzet, jauchzet dem Herren alle Welt”, it is epizeuxis. If altered this way: “Jauchzet, jauchzet dem Herren alle, alle Welt”, it is double epizeuxis. The next version, “Jauchzet dem Herren, jauchzet Ihm alle Welt, jauchzet und singet”, is anaphora. The analysis also features in detail the following devices: synonyma, asyndeton, polysyndeton, anadiplosis, climax, epistrophe, epanalepsis, and epanodos. (Krones, 2008, pp.29-64).

Georg Ahle’s examples are also quoted in the musical encyclopaedia by Johann Gottfried Walther (1684-1748) to illustrate rhetorical devices (Walther, 1732, p.228). Before expanding on the examples, Georg Ahle explains that it is as necessary for composers to employ rhetorical devices as it is for orators (Krones, 2008, p.34).

In several cases, the same rhetorical device has different names. Arnold Schmitz highlights that the distinction is ambiguous for several terms. He mentions the example of parenthesis (the inclusion of a lower section into the melody), which is difficult to distinguish from hyperbole or hyobole (leaving the melody from above) (Schmitz, 1955, p.180). Jan Wilbers refers to augmented and diminished steps as melodic parrhesia but also uses the term “saltus duriusculus” (Wilbers, 1995, pp.28-129).

A similar problem arises in relation to devices denoting a halt in the musical process, namely abruptio and aposiopesis. Dietrich Bartel (1997, p.167) notes that Athanasius Kircher (1601-1680) uses the term abruptio, and later homoioptoton, instead of aposiopesis. In describing aposiopesis, the Treatise by Meinrad Spiess (1683-1761) defines it as a halt in one or all voices and adds that it also can be called abruptio (Spiess, 1745, p.155). Johann Gottfried Walther (1732, p.41) defines aposiopesis as a halt in all voices. While Athanasius Kircher (1650, p.145) defines abruptio as a sudden stop in the musical process, Walther (1732, p.2) adds: “the fourth is not dissolved and the closing note is sounded by the bass only.”

The examples clearly show the occasional inconsistencies in the terminology of rhetorical devices. It is useful to bear in mind Philipp Melanchthon’s (1497-1560) advice, namely that one should not be unsettled by the diversity in terminology (Pintér, 2001, p.80).

The Baroque Practice of Interpreting Sheet Music

Musical notation, regardless of the musical style, poses a constant challenge for musicologists and performers alike. The incompleteness of scores is a daily experience. László Somfai remarks that musical notation is “undoubtedly imperfect” and “invariably changing” (Péteri, 1987, p.96).

The challenge is increasingly difficult and complex in early music.

Difficulties in reading and interpreting Baroque sheet music have three fundamental causes:

- Musical notation might seem not to have changed in the past 400 years. The same symbols were used by Monteverdi, Mahler, and Kodály. However, certain symbols have carried distinct meanings in different periods. Consequently, one must be familiar with the musical notation practices of earlier eras.

- Scores in use today contain numerous notations which were added by the publisher instead of the composer. With sufficient knowledge of the style, performers may be able to avoid these, but it is not possible to decide for some notations whether they were intended by the composer or the publisher. Unfortunately, a sizable portion of Baroque scores currently in use for performance is useless in this respect. János Hammerschlag’s words from 1952 should be taken to heart: “We should not continue this anachronistic publishing practice. We should attempt to offer authentic sores and verified text everywhere. […] We should not spread errors from unreliable editions. […] It is an entirely improper practice to insert anything into the text. Even instructions about dynamics and phrasing slurs should not be included…” (Szabolcsi and Bartha, 1953, p.220)

- Scores from the 17th and 18th centuries did not contain several pieces of information which now seem indispensable for the performance of a piece. This was discussed in studies from the early 20th century: “As early as 1900, some great music historians began to address the issue of how compositions which were deemed unchangeable might have contained more notes than what was notated in the score…” (Pernye, 1981, p.265)

Dynamics

Sheet music from the 17th and 18th centuries contained few notations in relation to dynamics. Even if they were present, they instructed actual dynamic changes and hardly ever referred to increasing or decreasing the volume. This is partly the reason why dynamics in many performances changes in blocks, that is to say, there are clearly separable forte and piano sections, with no graduality in between. When it comes to the dynamics of Baroque works, several musicians think of “terrace dynamics” first as the “default” dynamic characteristic of such music.

Undoubtedly, terrace dynamics did exist; various pieces can be clearly divided into loud and quiet sections. But if one considers what theoreticians of the period opined, it is easy to find that constant change in the dynamics of Baroque pieces signified a sort of play between light and shadow. Of the numerous descriptions, here I present two:

“In increasing and abating the voice, and in exclamations is the foundation of passion” (Donington, 1978, p.285).

“Learn to fill, and soften a sound, as shades in needlework, in sensation, so as to be like also a gust of wind, which begins with a soft air, and fills by degrees to a strength as makes all bend, and then softens away again into a temper, and so vanish” (North, 1887, sect. 106).

It is important to consider the following principles of Baroque dynamics:

- dissonance is always more pronounced than the dissolution,

- sections in a major key are usually louder than sections in a minor key,

- the first instance is usually natural (not muted) in volume,

(It is important to mention here that the fist dynamic notation in scores from the period was usually piano, often after the first cadence. It follows directly that one had to play louder before.) - imitation and fugue themes are to be played louder.

According to Claude V. Palisca, Baroque music is characterised by fire, extravagance, and outbursts of passion. “Behind the traits that mark music as baroque, then, are their reason for being: the passions” (Palisca, 1976, p.11-12). Such music requires unyielding, fiery, and passionate dynamic contrasts.

Notation of Articulation

Inscriptions from later periods cause the most confusion and difficulties in the field of articulation, especially because the notation of articulation signs has changed in the past centuries. In a similar way to dynamics, scores from the period contained few notations in relation to articulation. This is due to two factors: Baroque musicians knew the rules of articulation, which is why it was superfluous to notate them; and the abundance of notation might have cluttered the score. It is important to see that the lack of articulation notation does not mean that everything should be or need to be played the same.

The fundamental rules of articulation can be summarised in the following way:

- adjacent notes are mostly connected (legato),

- intervals which are larger than a second should usually be struck separately,

- elements with alternating notes should generally be slurred,

- the dissonance and its dissolution should not be separated,

- ascending scales should be struck separately, descending scales should be rather slurred.

In slow pieces, slurs (legato) can be employed more frequently, while fast movements (dances) require the notes to be struck separately instead.

In analogy to dynamics, articulation should also be refined and varied, even within one musical thought. Robert Donington writes: “the refinements can be varied from note to note: and no two notes running should necessarily be given quite the same degree or manner of separation” (Donington, 1978, p.285).

I present two examples to illustrate the refinement of articulation notation:

Legato was first used in the early 17th century. Before the slur, a silence of articulation (separation) must be inserted. The first of the notes under the slur is more accented, while the rest decline gradually in accent. Consequently, the notation of legato does not just concern articulation but also phrasing. Sometimes it is obvious that legato indicates the momentum of connected notes and its meaning with respect to articulation is secondary.

Legato can be interpreted in multiple ways. Bach denotes ordinary articulation with a long slur. (However, it is a valid question as to what constitutes a long slur…) In French music, pairs of eighth notes under a slur are mostly to be performed with unequal play. With Vivaldi, the long slur is an individual and unique solution, which should be taken seriously.

Staccato can be traced back to the early 17th century. It signifies, according to the practice today, the separation of notes (non-legato play). A great example for this is bar 3 of the first movement of Bach’s Oboe Concerto in F major. The sequence of eighth notes would have been performed by a string instrument player in the period with “one bow” (slurred or connected with modern terminology), which was customary for such steps. Bach denoted the deviation from ordinary articulation this way.

In French music, staccato terminated inegal play.

Rhythm

This aspect of music literacy used to be the most different from present-day practice. Contemporary music education places substantial emphasis on the performance of the rhythm according to the composer’s score. From the 1800s, it was indeed a requirement, but it was quite alien from the Baroque approach. As Harnoncourt explains: “The musician of today plays precisely what is indicated by the notes, little realizing that mathematically precise notation became customary only in the 19th Century.” (Harnoncourt, 1988. p.16).

Baroque musicians were keen to achieve rhythmic liberty and flexibility. The most prominent example for this is inequality, that is, the unequal performance of equally notated notes. Rhythmic flexibility, however, did not mean randomness. The performance was neither careless nor without rhythm.

The question arises as to why the music to be played was not notated exactly. The answers are provided by the theoreticians of the time.

“Of two notes one is commonly dotted [but] it has been thought best not to notate them for fear of their being performed by jerks” (North, 1959, p.223).

“It is very hard to give general principles as to the equality or inequality of notes, because it is the style of the pieces to be sung which decides it” (Montéclair, 1709, p.15).

Couperin comments with simplicity: “We write otherwise than we perform” (Couperin, 1716, p.38).

A great summary of the varieties of and conditions for inequality can be found in Chapter XIX of Robert Donington’s book titled A Performer’s Guide to Baroque Music (Donington 1978, pp.249-250).

Tilted inequality:

- notes fall naturally into pairs

- are mainly stepwise

- are the shortest occurring in substantial numbers within the passage

- are not longer than one pair to a beat

- are of graceful rather than energetic character

- form melodic figures rather than integral turns of melody.

Vigorous inequality is different from the tilted version in one main feature: the notes should be of an energetic rather than a graceful character.

One of the most disputed fields of early music performance is the interpretation of dotting. In current practice, the note is lengthened by its half, which was different in the Baroque period.

“To perform the dots in their value, it is necessary to hold on to the dotted quarter note, and pass quickly over the following eighth note” (L’Affilard, 1694, p.30).

“Since a proper accuracy is often lacking in the notation of dotted notes, a general rule of performance has become established which nevertheless shows many exceptions. According to this rule, the notes following the dot are to be performed with the greatest rapidity, and this is frequently the case. But sometimes notes in the remaining parts [determine the dotted lengths, or] a feeling of smoothness impels the performer to shorten the dotted note slightly” (Bach, 1753, p.23).

In his book titled On Playing the Flute, Quantz also discusses dotting. His remarks clearly show that one requires carefulness in interpreting documents and treatises about early music; it is not advised to select one sentence only and decide accordingly. In the beginning of section V, Quantz explains: “A dot standing after a note has half the value of the preceding note…” (Quantz, 1752, p.73).

A few pages later, however, he writes: “it is not possible to determine exactly the time of the short notes after the dot” (Quantz, 1752, p.77).

Based on descriptions from the time, it can be concluded that the extent of Baroque dotting is determined by the musical character. In slow pieces, the dotting is softer, while in fast pieces “the notes after the dot… are to be played more quickly”.

Sometimes it occurs that various styles of dotting are present in the same movement. In this case, the smallest dotting must be applied. In the Overture of Händel’s Messiah, the first bar features large dotted notes, while bar 8 contains small dotted notes. Consequently, the movement should be played with double dotting.

Additional problems arise when dotted rhythms and triplets are present in the same movement (even in overlapping voices). In such cases, the dotted rhythm may be played in a “triplet” way. In the gallant style of late Baroque music, the practice was not common anymore. Another problem occurs when duplets clash with triplets. Theoreticians of the time regarded these one of the most prohibited musical situations. The solution was to “assimilate” duplets to triplets.

Händel: Messiah Ouverture

Ornamentation

Ornamentation is an integral part of Baroque pieces and performance. As Donington puts it: “ornamentation is not a luxury in baroque music, but a necessity” (Donington, 1978, p.156). Several theoreticians regarded ornamentations as the factor which reveals genuine artists and musicians.

“Yet a true musician may distinguish himself by the manner in which he plays the Adagio, may greatly please true connoisseurs and sensitive and feeling amateurs, and may demonstrate his skill to those who know composition.” (Quantz, 1752, p.156).

“In repeating the Air [i.e. the first section], he that does not vary it for the better, is no great Master” (Tosi, 1723, p.93).

Fortunately, embellishing practices are well-documented, with countless detailed examples. One of the best known study is the book titled On Playing the Flute by Johann Joachim Quantz, which discusses ornamentation over several pages. The author lists simple intervals and proposes 20-25 ornaments for each. At the end of the chapter on Adagio performance, the ornamentation of an entire movement is presented. Georg Philipp Telemann wrote sonatas for pedagogical purposes to introduce beginners to ornamentation (Telemann, 1728/1732). In the sonatas, Telemann provides the base motif, followed by its embellished version. The study with methodical trios and scherzos, where ornamentation in trio performance is presented, is also of interest.

There are a few basic principles to consider with respect to ornamentation:

- Ornamentation is not just the variation of a melody as an idea but also a tool for emotional expression. As emotions intensify, the ornamentation becomes more dense. “Embellishments […] were expected to enhance the expression contained in the work in a highly personal way” (Harnoncourt, 1988, p.63).

- Simple ornaments should precede complex ones. However, the last appearance of the varied theme is not supposed to be embellished.

- The melody rests on the closing note, which, consequently, is usually not embellished.

- The length of cadences for vocals or wind instruments should not exceed what may be performed with one breath. By contrast, a “string player can make them as long as he likes, if he is rich enough in inventiveness. Reasonable brevity, however, is more advantageous than vexing length” (Quantz, 2011, sect. XV).

- Ceremonious and serios movements do not require ornamentation.

It is also important to mention here the two major national styles of the Baroque period: the French and the Italian. They were distinct in various aspects, including the custom of ornamentation. In the French style, the desired ornaments were notated relatively precisely. Since notations often differed by composer, and the same signs could even refer to distinct ornaments, some editions contain a table with the interpretation of the notation.

Ornaments are not “ad libitum” but form an integral part of the piece. A presumably French musician was recorded to complain: “Why does one not require them to play the various parts as they have been set?” (Harnoncourt, 1988, p.161).

By contrast, the Italian style of ornamentation required an extensive knowledge of harmony theory because embellishments often surround the main melody and connect intervals with passages, resulting in an embellished melody which resembles the original only slightly.

Quantz describes this in detail:

“The Adagio may be viewed in two ways with respect to the manner in which it should be played and embellished; that is, it may be viewed in accordance with the French or the Italian style. The first requires a clean and sustained execution of the air, and embellishment with the essential graces, such as appoggiaturas, whole and half-shakes, mordents, turns, battemens‚ flattemens‚ etc., but no extensive passage-work or significant addition of extempore embellishments. The example in Tab. VI, Fig. 26,3 played slowly, may serve as a model for playing in this manner. In the second manner, that is, the Italian, extensive artificial graces that accord with the harmony are introduced in the Adagio in addition to the little French embellishments” (Quantz, 2011, p.56)

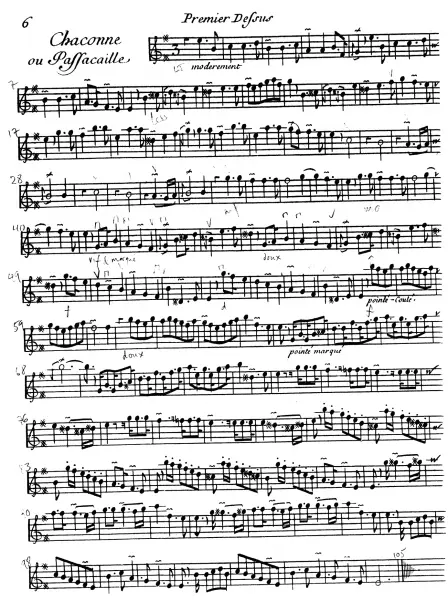

The difference between the two styles is evident from the two following examples. The first, an excerpt from Telemann’s methodical sonatas, illustrates the Italian style; the second, a dance movement by Couperin, the French. In Telemann’s score, the basic melody is in the upper row, with Telemann’s embellished version below. In Couperin’s score, there is no separate version for ornamentation as the melody embellished by the composer is presented in the first place. The examples also illustrate what has been remarked about articulation: in the French style, the staccato could terminate inequality (from bar 81).

Excerpt from Telemann’s Methodical Trios and Scherzos series

Couperin: Les Nations - Chaconne

Conclusion

In the contemporary musical scene, there is a wide variety of performance genres. With some exaggeration, basically anything can be performed in any way. There is a “magic spell” which musicians use to free themselves from the limitations of a given style: “This is my interpretation; this is what music is for me”. Undoubtedly, performance is greatly affected by personal intuition, sense of music, and musicality.

It is up to any mature performer to decide which path to take. However, we, music instructors, are convinced that we ought to provide our students with a curriculum which is appropriate from the perspective of music history and style. Although there is room for “interpretation”, it would be false to say that a 19th-century practice originated one or two centuries before. Rules which, verifiably, appeared in the 19th century cannot be regarded creations of the 17th and 18th centuries. This is not a question of musicality or interpretation but that of knowledge about styles.

It would be wrong to intermingle periods of music history because, as András Pernye put it: “This is a mere falsification of history” (Pernye, 1981, p.251).

References

- Adamik Tamás–A. Jászó Anna–Aczél Petra (2004): Retorika [Rhetoric]. Osiris Kiadó, Budapest.

- Affilard Michael L’ (1694): Principes trés-faciles pour bien apprendre la musique. Párizs.

- Algrihm, Isolde (1987): „Retorika a barokk zenében” [Rhetoric in Baroque Music]. In: Péteri Judit (ed.): Régi zene 2. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest. 40-49.

- Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel (1753): Versuch. Berlin.

- Bartel, Dietrich (1997): Musica Poetica. Musical-Rhetorical Figures im German Baroque Music. University of Nebraska Press, London.

- Buelow, G. J. (1987): „Retorika és zene” [Rhetoric and Music]. In: Péteri Judit (ed.): Régi zene 2. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Caccini, Giuliano (1977): La nuove musiche előszavából. In: Barna István (ed.): Örök Muzsika. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest. 106-111.

- Couperin, Francois (1716): Csembalóiskola [The Art of Harpsichord Playing]. Párizs.

- Donington, Robert (1978): A barokk zene előadásmódja [A Performer’s Guide to Baroque Music]. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Eggebrecht, Carl and Dahlhaus, Hans Heinrich (2004): Mi a zene? [What is the Music?] Osiris kiadó, Budapest.

- Hammerschlag János (1953): „A zenei díszítések világából” [From the World of Musical Decorations]. In: Szabolcsi Bence, Bartha Dénes (eds.): Emlékkönyv Kodály Zoltán 70. születésnapjára. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest. 199-220.

- Harnoncourt, Nikolaus (1988): A beszédszerű zene [Music as Speech]. Editio Musica, Budapest.

- Hayns, Bruce (2007): The End of Early Music. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Imre Mihály (2003): Retorikák a reformáció korából [Rhetoric from the Reformation Era]. Kossuth Egyetemi Kiadó, Debrecen.

- Jeppesen, Knud (1975): Ellenpont. A klasszikus vokális polifónia tankönyve [Counterpoint. A Textbook of Classical Polyphony]. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Kircher, Athanasius (1650): Musurgia Universalis. Francesco Corbelletti, Rome.

- Krones, Hartmut (2008): „Zur musikalischen „Rhetorik” in G. Ph. Telemanns Kantaten.” In: Adolf Novak-Andreas Eichorn (eds.): Telemanns Vokalmusik. Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim. 29-64.

- Kubik, Reinhold and Legler, Margit: Rhetoric, Gesture and Scenic Imagination in Bach's Music. Bach Network UK 2009.

http://www.bachnetwork.co.uk/ub4/kubik_legler - Marpurg, Friedrich Wilhelm (1978): Anleitung zum Clavierspielen (Berlin, 1755) 12. In: Robert Donington: A barokk zene előadásmódja. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Mattheson, Johann (1977): „Kern melodischer Wissenschaft”. (Hamburg, 1737) In: Barna István (ed): Örök Muzsika. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest. 150-158.

- Mattheson, Johann (1999): Der Vollkommene Cappelmeister. Bärenreiter, Kassel.

- Montéclair, Michael de (1709): Nouvelle méthode pour apprendre la musique. Paris.

- North, Roger (1887): Önéletrajz [Autobiography] (kb. 1695). Új kiadás: Jessopp, London.

- Palisca, Claude V. (1976): Barokk zene [Baroque Music]. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Peri, Jacopo (1977): Euridice – előszó [Euridice – Preface]. In: Barna István (ed.): Örök muzsika. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest. 103-105.

- Pernye András (1981): A nyilvánosság [The Public]. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Péteri Judit (1987): Beszélgetés Jos van Immerseellel [Conversation with Jos van Immerseel]. In: Péteri Judit (ed.): Régi zene 2. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Pintér Tibor (2001): Affektus és ráció. Descartes szenvedélytana és a barokk zenei affektuselmélet [Affects and Rationality. Passions in the Writings of Descartes, and the Theory of affect in the Baroque Music]. Phd Dissertation. Manuscript. ELTE BTK Esztétikai Doktoriskola, Budapest.

- Platón (1989): Állam [The State]. Gondolat Kiadó, Budapest

- Quantz, Joachim (2011): Fuvolaiskola [Flute School]. Argumentum Kiadó, Budapest.

- Rolland, Romain (1960): Zenei utazások a múlt birodalmában [Musical Journeys in the Realm of the Past]. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Schmitz, Arnold (1955): „Figuren”. In: Friedrich Blume (ed.): Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Allgemeine Enzyklopädie der Musik. Bärenreiter, Kassel. 176-184.

- Schönberg, Arnold (1971): A zeneszerzés alapjai [Basics of Composing]. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Somfai László (1987): Notáció és játékstílusok [Notation and Playing Styles]. In: Péteri Judit (ed.): Régi zene 2. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Spiess, Meinrad (1745): Tractatus. Johann Jacob Lotters seel. Erben, Augsburg.

- Telemann, Georg Philipp (1985): Singen ist das Fundament zur Musik in allen dingen. Eine Dokumentensammlung. Verlag Philipp Reclam, Leipzig.

- Tosi, Pier Francesco (1723): Opinioni de’ cantori. Bologna.

- Unger, Hans-Heinrich (1941): Die Beziehungen zwischen Musik und Rhetorik im 16-18. Jahrhundert. Konrad Triltsch Verlag, Würzburg.

- Vígh Árpád (1981): Retorika és történelem [Rhetoric and History]. Gondolat Kiadó, Budapest.

- Walther, Johann Gottfried (1732): Musikalisches Lexikon. Wolfgang Deer, Leipzig.

- Wilbers, Jan: Musikalisches Rhetorik im Bachs Matthäus Passion

http://members.home.nl/canopus/Rhetorik/14.%20Kapitel%20XVIIIa.%20Nvb%20001-026%20 - Wilson-Dickson, Andrew (1998): Fejezetek a kereszténység zenéjéből [A Brief History of the Christian Music]. Gemini Kiadó, Budapest.

- Wolf, Christoph (2009): Johann Sebastian Bach a tudós zeneszerző [Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician]. Park Könyvkiadó, Budapest.