Author: Mihály Duffek, Jr.

DOI: 10.5434/9789634902263/9

Abstract

This essay examines the sources of the autograph and other copies of two selected solo pieces, J. S. Bach's Cello Suites and Georg Philipp Telemann's Fantasies for Solo Flute used to make a bassoon transcription. Using the special literature on the subject of the Baroque style of playing in general, the articulation, ornamentation, dynamics and tempi of the two pieces were determined. along with the role and playing possibilities of the period bassoon. Aspects of the transcription include: a brief description of the habitual Baroque transcription and its tradition, presentation and evaluation of other bassoon transcriptions of the selected pieces, detailed aspects of the author’s transcription of the articulation, ornaments, dynamics, tempi and breathing. Also discussed are the purpose of the completed transcription, its role in education, and its place in the bassoon repertoire.

Keywords: bassoon, solo bassoon, baroque, transcription, Bach, Telemann

Introduction

I have always been fascinated by the lack of excellent solo pieces for the bassoon such as the Cello Suites by J. S. Bach, his Solo Sonatas and Partitas for the violin, or Telemann’s Fantasias for the flute, violin, and cello. I believe to have discovered some of the reasons, including the development of the instrument in the period. However, the bassoon has gone through a substantial transformation throughout the centuries, which has enabled the performance of certain Baroque solo pieces on it without any major loss in the musical message. Of the listed pieces, I decided to transcribe the first four of J. S. Bach’s Cello Suites (BWV 1007-1010) and G. Ph. Telemann’s 12 Fantasias for Flute (TWV 40:2-13), since the former works cover an appropriate range for the bassoon, while the latter pieces share resemblance with the bassoon in that they were also composed for a wind instrument.

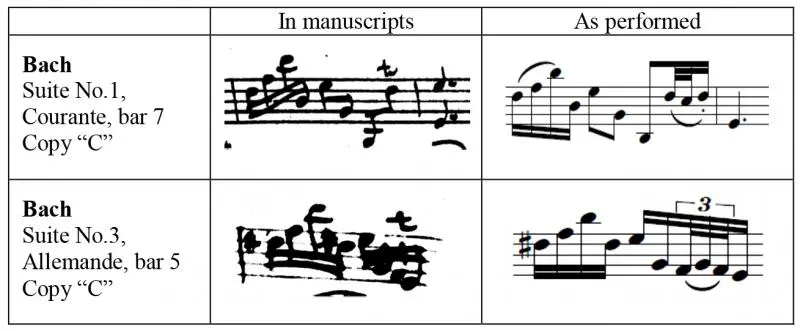

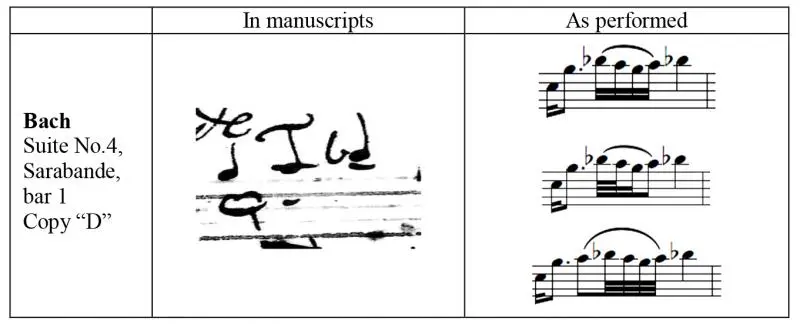

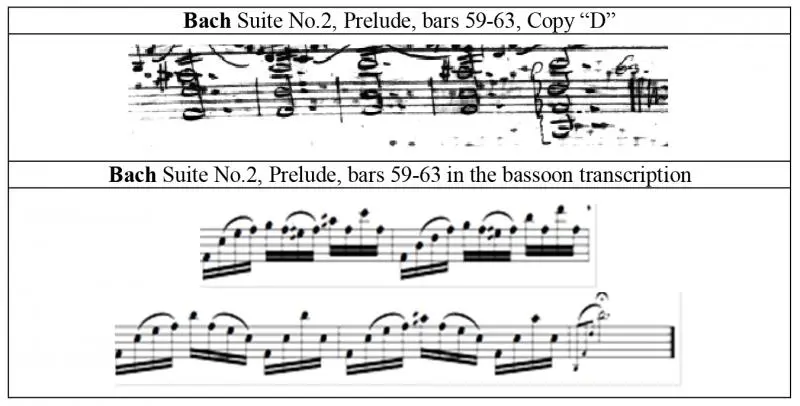

In transcribing Bach’s Suites, I could not rely on an autograph, so I turned to four copied manuscripts, which the literature refers to as sources A (copied by Anna Magdalena Bach), B (copied by Johann Peter Kellner), C (copied by Anonymous 402 and an unknown scholar), and D (copied by an unknown person). Critical editions presume the following origins: A, B, C, and D were written between 1727 and 1731, in 1726, in the second half of the 18th century, and in the 1790s, respectively (Beisswenger, 2000; Leisinger, 2000; Schwemer and Woodfull-Harris, 2000; Voss and Ginzel, 2007). Manuscripts C and D are more detailed and consistent, and are noticeably similar in the notation of articulations and ornamentation. Based on music notation, these two are more closely related than A with B or each of the two with any other manuscript. Therefore, I favoured in the process of transcription sources C and D as well as the critical edition based on them (Leisinger, 2000).

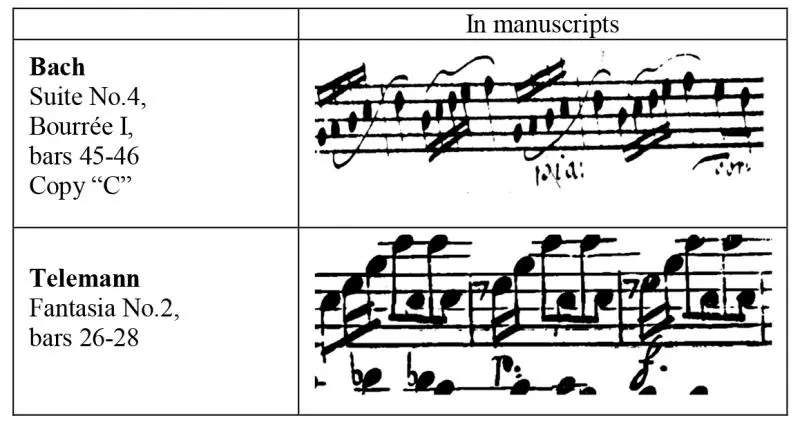

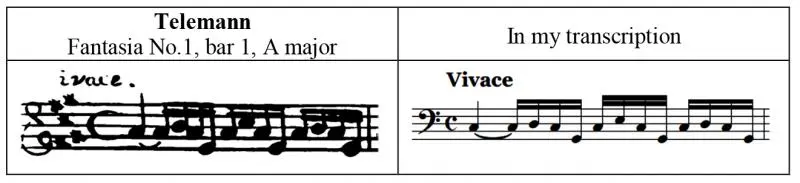

In transcribing Telemann’s Fantasias, I relied on the composer-approved edition, published around 1732/33 (Beyer and Brown, 2013; Hirschmann and Nastasi, 1999). In addition, the edition by renowned Baroque flautist Barhold Kuijken, which has a facsimile supplement, was also helpful (Kuijken, 1987).

Authentic Performance in Pieces by J. S. Bach and G. Ph. Telemann

In transcribing the selected works, it was important to understand and execute the style and performance of the period both theoretically and practically. The Baroque tradition of performance is different from the practice of subsequent periods, including that of today, in various aspects. One of the most important differences lies in performers’ relationship to sheet music. In the Baroque period, performers interpreted the works in a way that did not follow the score as rigorously as it is customary today. This is due to various factors, including the greater homogeneity of the musical and cultural sphere of the period as opposed to nowadays (when popular music and multiple genres of jazz are widespread; bearing in mind the practices with respect to folk music and classical music from the Middle Ages until the contemporary era). Another difference is implied by the listed reasons. The Baroque musical language, albeit different across regions and countries, was still more coherent than the wide variety of musical styles, genres, and ways of expression today. It can be concluded that the interpretation of Baroque pieces, which were notated with varying specificity, was a rather straightforward task for musicians at the time. Nowadays, I believe we may find help in the authentic interpretation of Baroque manuscripts through examining urtext (critical) editions, listening to so-called historical recordings, understanding historical scholarship, and holding discussions with historical musicians.

Composers and those who copied sheet music did not intend to reflect each musical element in the score. This is especially apparent in copies A and B of Bach’s Suites but can also be traced in the notation of Telemann’s embellishments. According to Donington (1978):

“The baroque musicians had at their disposal virtually the same standard musical notation as ourselves”, but “they left their text more open and its interpretation more flexible. […] Where we tend to trust as much as possible to the notation, they tended to trust as much as possible to the performer” (Donington, 1978, p.27).

He argues that one should start out from facsimiles, which contained little information, because that is precisely what Baroque musicians had at their disposal. The scarcity of notation in relation to performance does not mean that one should not strive for a rich and nuanced expression, however. As regards the performer’s role in Baroque music, we must consider the following:

“It is no service to a composer being scrupulously faithful to a written text which is not scrupulously notated, but deliberately left open to the performer’s initiative” (Donington, 1978, p.28).

If the performer has so much liberty as regards the details of the piece, what should be the guiding principle of authentic execution?

Before detailing the process of transcription, I find it important, for the above reasons, to provide an overview on appropriate articulation, ornamentation, dynamics, and tempo in Baroque performance. Since each topic could well be the subject of a separate study, I focused my research on thematic excerpts which can be found in the manuscripts or copies of works by Back and Telemann. Exploring and considering such components enable the adequate execution of a piece and, more importantly, facilitate its arrangement to another instrument, which often occurred in the Baroque era, as well (Harnoncourt, 1988). Based on the discussion above, I decided to choose a feasible version from the countless possibilities, in the hope that it would correspond to the variety of expectations and perspectives in relation to authenticity. In this respect, I relied on Donington’s (1978) definition, which reads:

“One’s interpretation of the music does not always have to be the same. Personality; individuality; temperament: there was room for all these at the time, and there is room for them now” (Donington, 1978, p.21).

Articulation

By articulation, we usually mean the slur or separation of subsequent notes or groups of notes (C. Dahlhaus and H. H. Eggebrecht, 1983). Generally, connected notes are denoted by a slur, while notes to be separated are marked with a dot, stroke, or wedge (C. Dahlhaus and H. H. Eggebrecht, 1983). The former stands for legato, the latter for staccato play. First, the theory of slurs and the practical execution of legato in the period should be introduced.

In the Music Encyclopaedia by the renowned 18th-century scholar Johann Gottfried Walther (1684-1748), which was published in 1732 and was reportedly part of Bach’s library (Wolff, 2009), the articulation slur is defined the following way:

“This sign often ties together several notes which are not of the same pitch but are located on different lines or in different spaces, thus signalling that just one syllable may be placed under them while singing; and on instruments they should be connected and played with one stroke of the bow” (Walther, 1732, p.359).

We can understand the adequate execution of the slur on wind instruments from the book titled On Playing the Flute, published in 1752, by flautist and composer Johann Joachim Quantz (1697-1773):

“if an arc stands above two or more, they must be slurred. Thus you must remember that only the note on which the slur begins needs to be tipped; the others found beneath the arc are slurred to it, and the tongue meanwhile has nothing to do” (Quantz, 2011, p.83).

Another guideline for authentic performance is provided in the book titled Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing (first published in 1756) by Leopold Mozart (1719-1787), who defined the slur as follows:

“Among the musical signs the slur is of no little importance […]. It has the shape of a half-circle, which is drawn either over or under the notes. The notes which are over or under such a circle, be they 2, 3, 4, or even mote, must all be taken together in one bow-stroke; not detached but bound together in one stroke, without lifting the bow or making any accent with it” (Mozart, 1998, pp.65-66).

Importantly, the first note of the slur had special significance in the period:

“The first of two, three, four, or even more notes, slurred together, must at all times be stressed more strongly and sustained a little longer; but those following must diminish in tone and be slurred on somewhat later” (Mozart, 1998, p.164).

This is in accordance with the remark by the influential artist Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1988), namely that the first note of the slur is accented and long, even if that means a deviation from the beat of the bar.

Harnoncourt (1988) also mentions that slurs in manuscripts from the period do not prescribe the way of performance as scores published nowadays do:

“If a slur covers larger groups of notes, a frequent practice in the music of Bach and his contemporaries, this means that here the musician should articulate in the manner with which he is familiar; the player is called upon to perform appropriately. A long slur therefore can also mean – and we must be clear about this – a subdivision into many short slurs ” (Harnoncourt, 1988. p.49).

The renowned expert Robert Donington (1978) is of similar opinion:

“Notated slurs sometimes occur, but as hints rather than as instructions; and as a rule very incompletely and inconsistently. It is for the performers to work out good and consistent bowings, breathings, articulation syllables, fingerings, etc.” (Donington, 1978, p.279).

This suggests that interpretation is not as easy and straightforward if manuscripts and copies from the period provide the source for the execution of slurs as it is with published and printed editions. To execute slurs by Bach and Telemann in a way that is authentic and faithful to the instrument, one should turn to Joseph Rainerius Fuchs’s (1985) thoughts about articulation, summarised in five points:

- Notes separated by a second should be connected; if the interval is greater, they should be separated. This is especially important for scale sequences in a certain direction. Furthermore, altering the direction of second steps often indicates the end of an articulation slur and the beginning of another one.

- Repeated rhythmic sequences, such as triplets and those with dotted notes or syncopation, are to be played under one slur. Shorter notes, especially with small intervals, should be connected; longer notes, especially with large intervals, should be separated.

- Ornaments consistent with the musical unity are to be connected, in a similar way to the consonant relief after a dissonance.

- The slur is meant for the reinforcement of metric weights, but there are examples for the disruption thereof.

- Themes, motifs, and phrases which constitute an independent musical unit should be performed with the same articulation.

After the slur, it is also important to investigate how the separation of notes occurs. In his above-mentioned Music Encyclopaedia, Walther describes it as follows:

“The staccato, or stoccato, is almost the same as the spiccato because the strokes are short, without bowing, and clearly separate. […] This articulation is notated, if the word staccato or staccato is not displayed, with a short upright line above or below the note” (Walther, 1732, p.575).

In Mozart’s Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing, the following definition can be found:

“Stoccato or Staccato: struck; signifying that the notes are to be well separated from each other, with short strokes, and without dragging the bow” (Mozart, 1998, p.72).

According to Quantz, the stroke (dash, wedge) denoting the staccato means more than the separation of notes; it determines the duration and even the accent of the note:

“little strokes are written above those notes which require the staccato. […] The general rule that may be established in this regard is as follows: if little strokes stand above several notes, they must sound half as long as their true value. But if a little stroke stands above only one note, after which several of lesser value follow, […] it must at the same time be accented with a pressure of the bow” (Quantz, 2011, p.214).

He notes that staccatos denoted by strokes and dots are to be played differently:

“For just as a distinction is to be made between strokes and dots without slurs above them, that is, the notes with strokes must be played with completely detached strokes, and those with dots simply with short strokes and in a sustained manner, so a similar distinction is required when there are slurs above the notes” (Quantz, 2011, p.206).

Robert Donington’s definition is similar to Quantz’s description of dotted staccatos:

“Dots, dashes and wedges are staccato signs not distinct from one another until very late in the baroque period, when the dot tended (no more) to imply a lighter staccato” (Donington, 1978, p.279).

For articulation on wind instruments, breathing and the use of tongue are crucial, which I present based on Quantz’s guidelines.

Breathing

All musicians playing wind instruments know that it is vital for the performance to devise a strategy of taking breath at the right time. Quantz (2011) assists performers with three rules in finding the appropriate time to breathe.

The first underscores thematic progression, whereby one must take breath before the main motif is repeated or a new thought is introduced to ensure proper separation.

The second rule suggests that one should breath after long notes instead of after short notes or at the end of the bar.

According to the third, one is advised to take breath before significant interval jumps.

In Quantz’s (2011) explanations which accompany the provided excerpts, the note after which taking breath is possible is denoted by a stroke, which is also the sign for staccato.

Use of the Tongue

Quantz (2011) draws a parallel between the use of the tongue and vocal sound production because wind instrument players must achieve airflow while pronouncing small syllables:

“These syllables are of three kinds. The first is ti or di‚ the second tiri, and the third did’ll” (Quantz, 2011, p.81).

Ti is used for moderately quick, equal notes and di for slow and sustained notes as well as exceptionally quick sequences. Tiri is reserved for dotted notes, while did’ll is used for quick passage-work when simple tongue is not sufficient.

Bearing in mind the present-day methodological practice of the bassoon, I must add that every syllable should be pronounced using back vowels. The most common vowels are a, o, and u, for example ta, to, tu should be pronounced instead of ti; da, do, du instead of di, etc. (Gallois, 2009). This is necessary for the proper functioning of the vocal tract (from the throat through to the lips), which is not covered in the present study extensively.

After discussing the basic theoretical and practical aspects of articulation, I turn to the ornamentation, dynamics, and tempos in works by Bach and Telemann.

Ornamentation

The question of embellishments is one of the most exciting components of authentic interpretations.

“Baroque ornamentation was […] originally without notation, later increasingly supported by notation, but never altogether replaced by notation” (Donington, 1978, p.156).

There were various small ornaments, the units of which were “quite remarkably inconsistent in their names and their signs; but much less inconsistent in their manners of behaviour” (Donington, 1978, p.174).

From the 1730s (Wolff, 2009), Bach was one of the pioneers of the standardisation efforts in relation to ornamentation. The goal was to make the notation of ornaments as well as their execution in practice unambiguous. The same intention can be traced in Bach’s book titled Clavierbüchline vor Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, published around 1720:

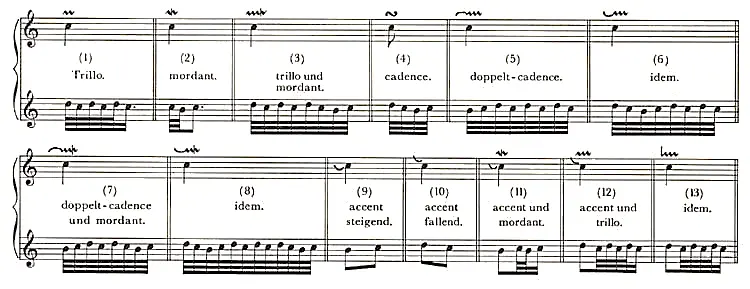

Figure 1: Playing ornaments – J. S. Bach: Clavierbüchline vor Wilhelm Friedemann Bach

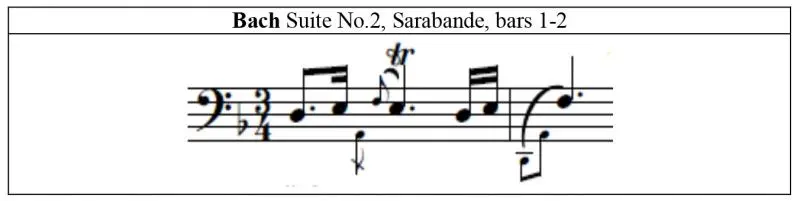

Nevertheless, some ambiguities did remain in the notation and performance of ornaments. Of the hand-written copies of Bach’s Cello Suites, C and D contain more notations of ornamentation as the two earlier copies (A and B), but none employ the system according to Figure 1 (mostly the tr notation is used, which is not featured in the figure). This corroborates Donington’s (1978) statement quoted above, namely that different notations referred to a sort of basic formula of embellishments. The opposite could also be true, however, as evidenced by Telemann’s only notation, +, which could be interpreted by the performer as the use of multiple distinct ornaments.

It can be concluded that several notations may refer to the same embellishment, while the same notation might refer to various ornaments. To recognise and independently execute ornaments irrespective of the notation, it is necessary to delve into the most common ornament types and their performance in pieces by Bach and Telemann.

Appoggiatura

Grace notes, or appoggiaturas, are ornaments which are not overly frequent in manuscripts. They are defined by Quantz and Mozart the following way:

“To avoid confusion with ordinary notes, they are marked with very small notes, and they receive their value from the notes before which they stand” (Quantz, 2011, p.81).

“The appoggiature are little notes which stand between the ordinary notes but are not reckoned as part of the bar-time. They are demanded by Nature herself to bind the notes together, thereby making a melody more song-like. […] the following and not the preceding note belongs to the appoggiatura” (Mozart, 1998, pp.208-209).

Table 1: Notation of the appoggiatura

Table 1: Notation of the appoggiatura

The two authors also have similar views on the correct performance of the appoggiatura:

“Appoggiaturas must be tipped gently with the tongue, allowing them to swell in volume if time permits; the following notes are slurred a little more softly” (Quantz, 2011, p.100).

“Here is now a rule without an exception: The appoggiatura is never separated from its main note, but is taken at all times in the same stroke. […] it is quite easy to accent somewhat gently, letting the tone grow rapidly in strength and arriving at the greatest volume of tone in the middle of the appoggiatura; but then so diminishing the strength, that finally the chief note is slurred on to it quite piano” (Mozart, 1998, pp.209;214).

There are two main kinds of appoggiaturas: accented appoggiaturas, on the downbeat, and passing appoggiaturas, on the upbeat. These can be executed in practice in the following way:

“Accented appoggiaturas, or appoggiaturas which fall on the downbeat, […] are held for half the value of the following principal note. […] The passing appoggiatura […] is again tipped briefly, and reckoned in the time of the previous note in the upbeat” (Quantz, 2011, pp.100-101).

“The long appoggiatura is therefore sustained the length of time equivalent to half the note […]. What the note loses is given to the appoggiatura. […] Passing appoggiature do not belong to the time of the principal note to which they descend but must be played in the time of the preceding note” (Mozart, 1998, pp.209;221).

The role of accented appoggiaturas must be kept with care because, as Donington (1978) explains, they create dissonance, which is harmonically dissolved by the principal note. It is a basic component of Baroque musical expression that every dissonance is more accentuated than the consonance onto which it dissolves.

Quantz (2011) prescribes that the duration of appoggiaturas must be determined by the performer irrespective of the note value in the score. Besides selecting the correct duration of denoted grace notes, performers should also be able to execute appoggiaturas adequately and tastefully even if the composer failed to include them in the score.

Trill

Trills constitute a group of ornaments common in manuscripts, including versions such as the half-trill (praller) and the mordent. The trill is an ornament whereby two adjacent notes (a principal and auxiliary one) are alternated quickly over multiple times. This is usually denoted by “tr” or “+” over the note to be embellished (Mozart, 1998; Donington, 1978).

Table 2: Notation of the trill

A trill is complete with a grace note (appoggiatura) and a succeeding note:

“Each shake begins with the appoggiatura that precedes its note, and the appoggiatura may be taken from above or below. The ending of each shake consists of two little notes which follow the notes of the shake, and are added to it at the same speed. They are called the termination. If, however, only a plain note is found, both the appoggiatura and termination are implied, since without them the shake would be neither complete nor sufficiently brilliant” (Quantz, 2011, pp.108-109).

The correct way of playing appoggiaturas has already been discussed. As for turned endings (Nachschläge), Mozart and Donington offer the following description:

“Nachschläge are a couple of rapid little notes […]. The first of these two notes is taken by the neighbouring higher or lower note, and the second is a repetition of the principal note. Both little notes must be played very rapidly and be taken only at the end of the principal note before the lead into the following note. […] These Nachschläge must in no way be strongly attacked, but slurred smoothly on to their principal note […]. In the long, descending intermediate cadences, too, it is always better by means of a few little notes which are slurred on to the trill as a tum, and which are played somewhat slowly, to fall directly to the closing note” (Mozart, 1998, pp.231;239).

Donington describes two possible methods of ending: one should be played in the way described by Mozart; the other consists of one note, in anticipation of the following note.

“The choice of ending, if not indicated, is at the performer’s option; but one or the other is obligatory on full trills” (Donington, 1978, p.197).

Quantz (2011) and Mozart (1998) agree that two trill types are conceivable: one with minor second and one with major second. The correct use is determined by the notes in the key and the principal note.

As for the speed of trills, both authors refer to the character of the given movement as the main determining factor.

“The trill can be divided into four species according to its speed: namely into slow, medium, rapid, and accelerating. The slow is used in sad and slow pieces; the medium in pieces which have a lively but yet a moderate and gentle tempo, the rapid in pieces which are very lively and full of spirit and movement, and finally the accelerating trill is used mostly in cadenzas” (Mozart, 1998, p.236).

There are two additional aspects mentioned in relation to speed. First, the higher the register of the trill, the quicker it should be played; in addition, it is advised to play lower registers more slowly. Second, the aural environment, that is, the acoustic characteristics of the concert hall should be taken into account. It is easy to see that a slower trill is more appropriate for resonant spaces, while dry halls require quicker trills.

Half-trill

One of the most frequent versions among incomplete trills was the half-trill (pralltriller). This is an upbeat ornament of four notes whereby the upper auxiliary-principal step is to be played twice. Donington mentions that “above a certain speed, the four notes have a natural tendency, for lack of time, to become three; i.e. the half-trill (Pralltriller) is turned into an inverted mordent (Schneller)” (Donington, 1978, p.197). In manuscripts, it is presumed to have been notated in the same way as the complete trill (“tr” or “+”), leaving the choice of the adequate ornament with the performer.

Table 3: Notation of the half-trill

Mordent

Mordents are also ornaments on the upbeat, consisting of three notes, with the first as the main one. Based on the direction of the step towards the auxiliary note, they can be either upper or lower. “This is the regular (lower) mordent of the main baroque period” (Donington, 1978, p.198). They were usually denoted by a short squiggle: ![]() , occasionally with a vertical line through it:

, occasionally with a vertical line through it: ![]() , clearly indicating a lower mordent.

, clearly indicating a lower mordent.

As with half-trills, mordents were not specified unambiguously in manuscripts (the notation was “tr” or “+” as before), leaving the decision to the performer’s sense of style. The lower mordent can be employed in cadences, while the upper mordent might prove useful in performing dense musical material with consistent rhythm.

Table 4: Notation of the mordent

Table 4: Notation of the mordent

Turn

Donington (1978) defines the turn (doppelschlag) as ornamentation around a main note by upper and lower auxiliary notes. The most common notation for it was a wavy line, indicating the direction of the sound: ![]() . The ornament appears usually between upward minor or major seconds.

. The ornament appears usually between upward minor or major seconds.

Table 5: Notation of the turn

Table 5: Notation of the turn

Mozart describes its performance as follows:

“The Doppelschlag is an embellishment of four rapid little notes, which occur between the ascending appoggiatura and the note following it, and which are attached to the appoggiatura. The accent falls on the appoggiatura; on the tum the tone diminishes, and the softer tone occurs on the principal note” (Mozart, 1998, p.229).

The doppelschlag is usually taken under the same slur as the preceding appoggiatura and the subsequent principal note. This corroborates Mozart’s stance, namely that the appoggiatura is the most accented, unlike the doppelschlag under the slur and the subsequent principal note.

As for the direction of the doppelschlag, two versions can be distinguished (five according to Hans-Martin Linde), which are described by Donington as follows:

“The standard (upper) turn begins with the upper auxiliary, passes through the main note, touches the lower auxiliary, and returns to the main note. The inverted (upper) turn begins with the lower auxiliary, passes through the main note, touches the upper auxiliary, and returns to the main note” (Donington, 1978, p.200).

The ornament could be on both the upbeat and downbeat, corresponding to the following musical roles and expressive functions:

“The turn may be accented, as an on-the-beat ornament, with a function equally melodic and harmonic; or unaccented, as a between-beat ornament, with a melodic function” (Donington, 1978, pp.199-200).

The latter (unaccented) is more frequent, although the notation is ambiguous because the ornament should be represented between two principal notes.

Dynamics

Dynamics stands for decreasing or increasing the volume, which is an integral part of every musical performance. In the Baroque notation, including Bach’s Suites and Telemann’s Fantasias, the most frequent signals to performers were the letters “f” (forte) and “p” (piano). Quantz (2011) and Mozart (1998) illustrate this with the analogy of light and shadow, which enables a “varied performance” (Quantz, 2011, p.127-128).

Table 6: Notation of dynamics

Table 6: Notation of dynamics

The alternation between the forte and piano play can occur for larger musical units as well as specifically prescribed for given bars and notes (Donington, 1978). The former provides refinement among the formal and thematic connections of a movement. As Quantz puts it:

“If in an Allegro the principal subject (thema) frequently recurs it must always be clearly differentiated in its execution from the auxiliary ideas. […] the subject can always be made sensible to the ear in a different manner by the liveliness or moderation of the movements of the tongue, chest, and lips, and also by the Piano and Forte. In repetitions generally, the alternation of Piano and Forte does good service” (Quantz, 2011, p.134).

The latter regulates the accents within a given bar and highlights the modified notes alien to the key (Mozart, 1998, p.272). Donington (1978) suggests to specify the dynamics of major units beforehand, even if there are no instructions. He offers the following advice about the ordering principle of minor dynamic changes:

“Rising dynamically to the peak of an ascending phrase, and falling away from it again as the melody descends, is one of the most natural of music responses. This can often happen intuitively, within the yet larger planning (best pre-concerted) of loud and soft passages” (Donington, 1978, pp.286-287).

Harnoncourt (1988) proposes three aspects for minor dynamic changes, resulting in an increased volume invariably. First, harmonic emphasis is important, namely that dissonant harmonies should be louder than their consonant relief, even if the latter is unaccented. Second, the rhythm must be kept in mind; in other words, if a shorter notes is followed by a longer one, the latter should be played louder. Donington (1978) provides the example of the longer note of syncopated rhythms and the dynamic emphasis on the even-metre hemiola in odd-metre cadences. Third, emphatic stress should be considered by accentuating and prolonging the top notes of a melody as opposed to preceding and following notes.

Tempo

The choice of tempo was a rather subjective component of Baroque performance, leaving great liberty with the performer in the adequate choice. Partial support is provided by the characterisation of the movements, which were dance movement titles for Bach’s Suites (e.g., Allemande, Sarabande, Courante, etc.) and Italian terms for Telemann’s Fantasias, which were already common at the time (e.g., Adagio, Andante, Allegro). However, it cannot be said for sure that one tempo is the only right choice:

“Tempo is a function of interpretation, and can only be right or wrong for a given interpretation. That interpretation, indeed, can be better or worse; but there is usually a considerable margin for individuality within the boundaries of the style” (Donington, 1978, p.237).

Among several subjective considerations, Donington mentions some objective aspects which provide assistance to performers in the choice of the most adequate tempo:

“In the same music, resonant acoustics or large forces may require a slower tempo than dry acoustics or small forces” (Donington, 1978, p.237).

The general advice is to play fast movements somewhat slower and slow movements somewhat faster. Deviating from this is only appropriate with great confidence in one’s instrumental abilities and message:

“To some extent, tempos on the fast side may be carried off by really dazzling brilliance; and tempos on the slow side may be carried off by really inspired intensity” (Donington, 1978, p.243).

Overview of the History, Use, and Possibilities of the Bassoon from the Period

In the early 18th century, the term “bassoon” did not refer to the current model but to a dynamically evolving member of a bass instrument family. According to descriptions by J. Walther (1732) and J. Mattheson (1713), the simultaneous use of multiple bassoon-like instruments was due to the necessity to play in different registers. The other instruments (e.g., pommer, kortholt, dulcian) were produced from a block of wood. It was only in the 1700s when the bassoon with its several wooden joints became common. W. Waterhouse (2003) suggests that the Italian term “fagotto” spread because it referred to a bundle of sticks or firewood. Ottó Oromszegi (2003), renowned researcher of the history of the bassoon, estimates that the process from a block instrument to one compiled from joints lasted about a century. In that period, the joint-based instrument became increasingly dominant, with improving keys. The bassoon made from joints had a range from A/B-flat to f’/g’ (Walther, 1732).

Originally, the instrument was used in orchestral pieces, operas, and chamber music as an accompanying bass instrument. This is shared by Donington, who writes:

“The primary function of the baroque bassoon was continuo work: either as a single melodic bass instrument in chamber music; or doubling with string instruments (or occasionally replacing them for entire passages or movements) in the orchestra. And once more, this orchestral doubling of the bass line by bassoons (as many as four or even six in big ensembles) was taken for granted, in suitable movements, without necessarily being indicated in the score” (Donington, 1978, p.94).

Quantz (2011) also discusses the importance of the bassoon in the bass play of the period because it was used even if no wind instruments were prescribed in the sheet music (see: Quantz, 2011, p.198).

It was the Italian master Antonio Vivaldi who discovered the bassoon as a solo instrument: he composed about 39 bassoon concertos. Besides Vivaldi’s bassoon concertos, the Sonata in f minor by Georg Philipp Telemann marked another important advancement as it contained the term “fagotto solo” to denote the principal voice.

The methodology and style of Baroque bassoon performance are difficult to reconstruct because no methodological guidelines have remained which could provide information on the handling of the instrument (Oromszegi, 2003). Quantz (2003) makes some remarks in his book titled On Playing the Flute about the correct use of the instrument (see: Quantz, 2011, pp.93-94). His observations and suggestions are not comprehensive but are still valid with respect to the handling of both French and German contemporary bassoons.

According to Donington, the “bassoon has been, and still remains, the most idiosyncratic of reed instruments, with much variety both between individual bassoons and between individual players” (Donington, 1978, p.94). In Jean-Laurent de Béthizy’s words, the bassoon is a “strong and brusque” instrument, which in professional hands produces “very sweet, very gracious and very tender sounds” (Béthizy, 1754, p.305). The extreme adjectives in the quotes imply that players could produce sounds of several characters. Musicians who were the most refined with their instruments got the most praise, which is even true today: to perform solo pieces by Bach or Telemann requires a high level proficiency with the instrument as well as advanced musical expression abilities.

Considerations of Creating Bassoon Transcriptions

It was common in the Baroque era to compose transcriptions, which did not just mean the arrangement of the composer’s own works from the original instrument to another but also the paraphrasing of other composers’ pieces, which was considered as a gesture of homage in the period. Even Bach made transcriptions of his own works and contemporaries’ compositions. For example, the Lute Suite in g minor (BWV 995) is the transcription of the Cello Suite in c minor (BWV 1011) (Leisinger, 2000). Although the Bach Suites and Telemann Fantasias I selected were transcribed by neither the composers themselves nor other musicians from the period (to my knowledge), there have been various transcriptions recently. These have been usually made by instrumental performers in an attempt to create a performer-oriented score which considers the characteristics of their instrument. Before I introduce the considerations with respect to my transcription, I briefly summarise the problems with the existing arrangements.

Based on my research of existing editions, with special focus on the 2011 bassoon transcription of Bach’s Suites by bassoon artist Arthur Weisberg, I have found the following. Some questions with respect to performance can be clarified based on commentaries attached to the editions, but if one only looks at the score itself, the solutions suggested by transcribers in the accompanying text cannot be deduced directly (this is especially true for the selection and performance of embellishments as well as the possible performance of chords in Bach’s works). I believe that it is not enough to explain the desired performance in the explanation attached to the edition; if possible, it should be clear from the musical notation alone, which helps the performer substantially and makes the transcription consistent and traceable. Of course, the performers’ liberty allows them to deviate from the score, which Donnington (1978) argues is justified for manuscripts from the period, but the transcription should nonetheless be easy to follow for performers, who are able to produce a slightly different individual version once they understand the logic of the piece. With all due respect to the transcribers’ efforts and intentions, I must say that the scores contain little to no consistency. Moreover, they even have performance elements which are alien to the style, which is why existing transcriptions are rather subjective versions. I decided to address and resolve the issues by composing my own transcription, which is strictly based on sources from the period.

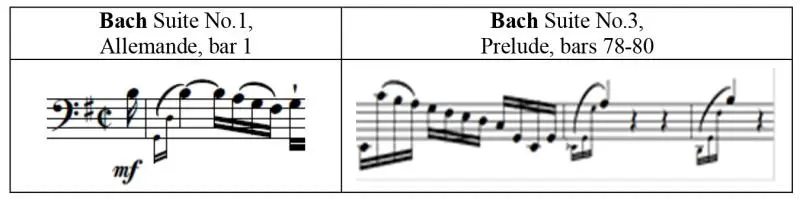

Key

In the process of transcription, there are two unavoidable questions: whether the piece can be performed on the bassoon in the original key and whether it is permissible to alter the original key in a transcription. The latter was answered by Baroque composers: even Bach himself often changed the key for a transcription, as evidenced by the Lute Suite (g minor) and the Cello Suite in (c minor). The answer to the former is yes for the four Cello Suites because Weisberg (2011) kept the original keys and I saw no reason to do otherwise.

Telemann’s Fantasias, however, would prove an insurmountable challenge to bassoonists if kept in the original key, due to the need to play a very quick musical material in an often quite high register and the several keys which are difficult to play. I took into account an additional consideration, namely that the range should be in a similar register than on the original flute. Consequently, I decided to keep the notation and simply transpose the treble clef into a bass clef. The result was, for the first Fantasia for example, the conversion of the original A major to C major.

Table 7: Transposing Telemann’s Fantasias

Table 7: Transposing Telemann’s Fantasias

I deviated from the described principle for three Fantasias only to ensure a transcription adequate for the instrument: No.4 from B-flat major to D major (instead of D-flat major), No.5 from C major to F major (instead of E-flat major), and No.12 from g minor to c minor (instead of b-flat minor)[1].

Articulation

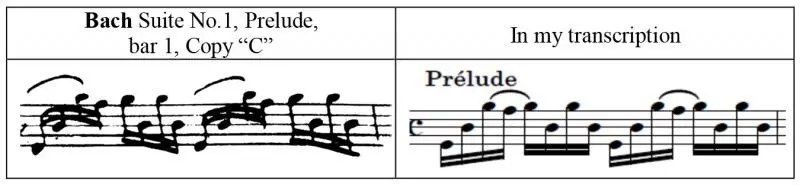

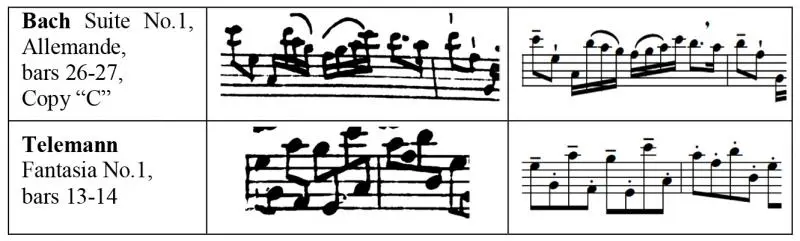

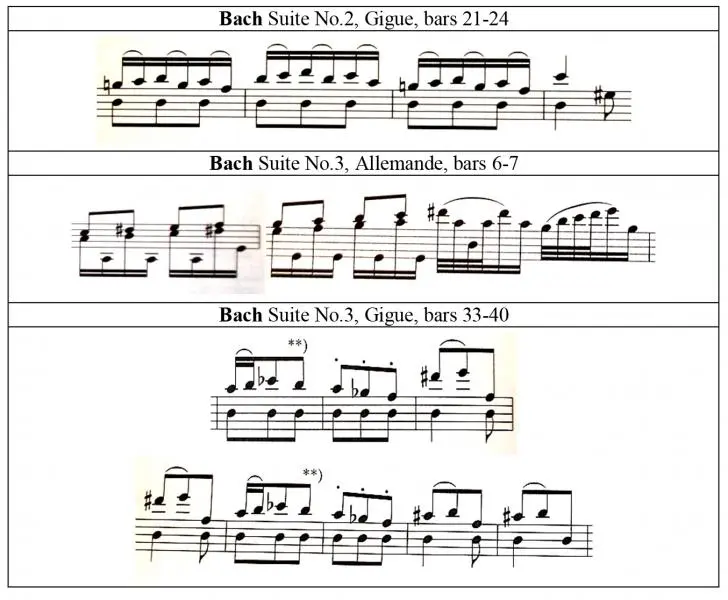

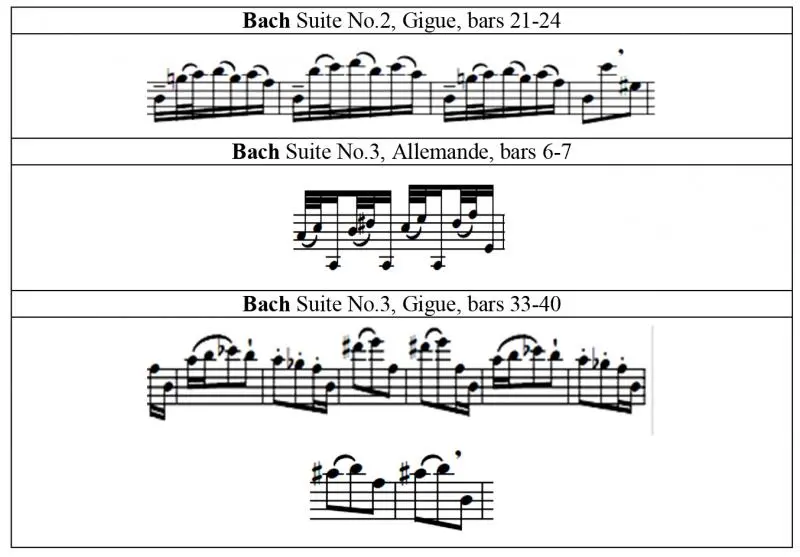

As regards articulation, difficulties arise in the interpretation of manuscript sources. In Bach’s Suites, for example, slurs and staccato notations are not consistent across the copies, and are occasionally imprecise and difficult to make out. I turned to the slurs and staccato notations of urtext editions for clarification. If I deemed necessary the modification of a slur from the original due to instrumental adequacy, I stuck to Fuchs’s organising principles. The resulting articulation elements were kept throughout the entire movement, according to the practice of the period.

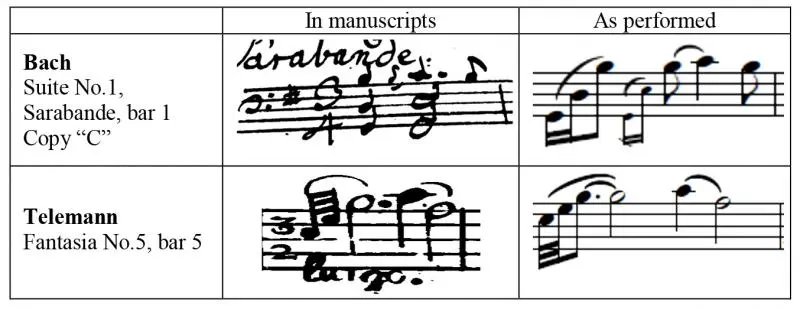

Table 8: Different slurs from the original

Table 8: Different slurs from the original

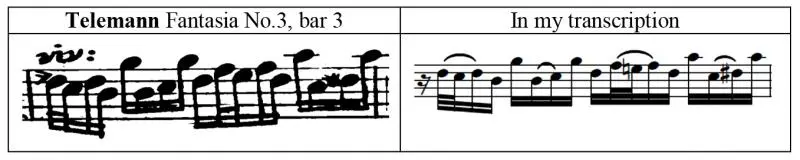

Although slurs in Telemann’s Fantasias are less ambiguous and correspond to instrumental characteristics better, I added several new slurs which are not present in the original to ensure playability on the bassoon. These were also kept throughout the movement.

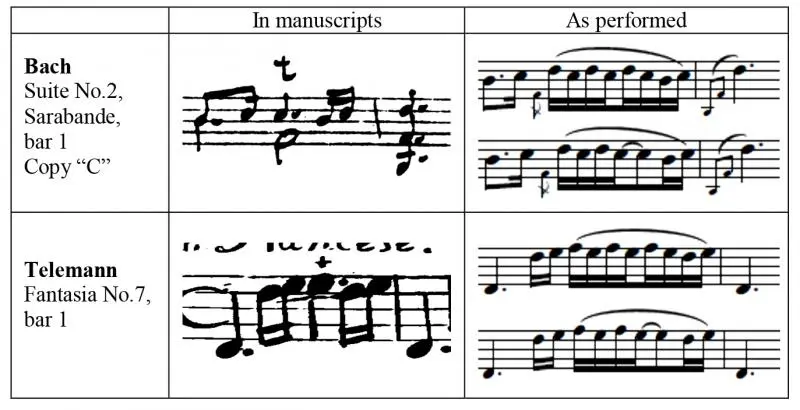

Table 9: Introducing new slurs

Table 9: Introducing new slurs

In Bach’s staccato notation, I followed copies C and D and denoted staccato with a stroke, unless all four sources prescribe a dot. It has been discussed based on Quantz’s (2011) description that a staccato with a dot does not break the continuity of music as opposed to the staccato with a stroke, which represents a more significant emphasis and highlight and breaks the continuity of music. Performing the emphasised notes with a stroke does not mean invariably a short division struck strongly with the tongue. In some cases, the stroke only prescribes that a certain note should be emphasised in contrast to others, whereby the brevity and strong initiation are not as important as dynamic accentuation, which can be achieved by a large blow of air. This is notated with a tenuto sign in my transcription as it refers to the adequate playing technique unambiguously. In conclusion, I also used tenuto signs occasionally, in addition to the dots and strokes of the copies.

Staccato notations are rare in Telemann’s Fantasias, and even if they occur, the emphasising stroke appears only. Based on the above, I found it necessary to specify note durations in these pieces, as well. To ensure proper performance, the chosen solution was the dynamic highlight using staccato and tenuto notation.

Table 10: Tenuto and staccato notation

Table 10: Tenuto and staccato notation

Breathing

The strategy of taking breath for a movement might differ across performers. The strategy ought to be devised according to Quantz’s (2011) remarks and should be maintained throughout the entire performance. If the execution is not successful, shortness of breath may occur, causing a distraction from the musical message and adversely affecting the sound. I must add to Quantz’s remarks that the exhaling of used air is a common practice nowadays. If a player deems its usage important, based on physical requirements, then it should be denoted in the score in a similar way to points of taking breath.

In contemporary practice, the time to take breath is denoted by a stroke between two notes. The performance is similar to Quantz’s (2011) description: the note before taking breath shortens to allow time for inhaling. Since the strategy of taking breath is quite complex across individuals, my transcription provides a mere suggestion in the matter and does not exclude other points of inhaling or exhaling.

Ornamentation

The theoretical and practical execution of ornamentation from the time has been discussed. But what should be done if one needs to perform chords, multiple sounds, or embellishments at the same time, as it is usual with Bach? Before addressing ornaments, let us turn to chords and multiple sounds. Since the bassoon is not able to produce multiple voices with the traditional technique, textures of two or more voices are represented by appoggiaturas in my transcription. If the melody has no ornaments (appoggiatura, trill, or turn), the lowest note of the chord is played first, followed by the rest until the highest note, all under one slur.

Table 11: Converting a chord into appoggiaturas

Table 11: Converting a chord into appoggiaturas

If the rhythm is not overly dense, the appoggiaturas of the chord may be upgraded as principal notes, which often occurs with Telemann, especially during slow movements.

Now it is time to discuss embellished principal notes which are preceded by one or more appoggiaturas. The embellishment, say the appoggiatura or trill, is usually in an accented position. Consequently, if a Bach copy contains an embellishment for the highest note in a chord, the chord should be played immediately before the ornament, that is, in an unaccented position. In my notation, these chord-substituting appoggiaturas are denoted by a crossed stem.

Table 12: Appoggiatura and trill in the bassoon transcription

Table 12: Appoggiatura and trill in the bassoon transcription

The duration of grace notes and appoggiaturas are different across Bach copies, which I tried to incorporate in the notation of the transformed chords. As a general rule, eighth notes were employed for chords if time and note density permitted. If there was little time due to the unusual note density or the quick tempo, sixteenth notes were used.

In Bach’s works, chords and multiple notes can also occur in other ways. For simultaneous multiple chords, sometimes there is a bass voice under the upper voice, resembling a pedal point.

Table 13: Pedal point

Table 13: Pedal point

The pedal point can only be preserved in the transcript if it becomes a principal note, which changes the rhythm of the melody, however. There are various ways of how to do it in a way which fits the instrument. I used my own instrumental experience to create the version for the bassoon.

Table 14: Pedal point in the bassoon transcription

Table 14: Pedal point in the bassoon transcription

In some cases, it is possible to employ a musical component which has a different rhythm from the original to replace chords. Source D of the Cello Suites converted the dotted half notes in the closing bar of the second Suite into sixteenth notes. Leisinger (2000) also mentions the possibility of playing a sequence of sixteenths instead of chords, which can be executed in various ways. I found the variation published by Ede Banda (1993) to be the most inventive, which is also adequate for the bassoon with a few slur modifications.

Table 15: Chords converted into semiquavers

Table 15: Chords converted into semiquavers

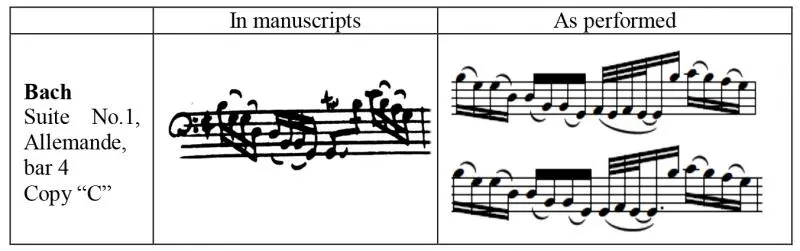

In the bassoon transcription of Bach’s Cello Suites, the exclusion of certain notes from polyphonic textures proved to be inevitable. The exclusions affected mainly the upper voice of octave duplications which concluded the end or first half of motifs or movements. The procedure is not alien from the Baroque practice: in Telemann’s Fantasias, for example, the closing note often jumps from the leading note to the relief an octave below. The phenomenon is also present in the Cello Suites, in which not all closing notes are duplicated to the octave, but sometimes there is an upward step of a major seventh to the dissolving closing note.

Dynamics

In the chapter on performance, the principles regarding dynamics have been discussed, namely that composers mostly used the notations forte (f) and piano (p) to denote a change in volume for a major or even minor section. Altering the dynamics is also important in articulation, which is governed by articulation signs, rhythmic elements, and the direction of the melodic sequence. Minor emphases, however, are not denoted in manuscripts and editions from the period as the desired dynamic change was clearly signalled for the performer by the articulation sign, rhythmic element, or the direction of the melodic sequence. Donington (1978) and Weisberg (2011) also argue that performers should use the listed signals as well as their own imagination and taste in selecting the dynamics of a piece. Therefore, the occasionally denoted dynamics in my transcription offer a starting point only for comprehensive dynamics (f, mf, mp, p), while the fine-tuning is open to the performer’s taste.

Tempo

In transcriptions for various instruments, including Weisberg (2011), publishers specify the suggested tempo in beats per minute. It is important take Weisberg’s (2011) suggestions into account, but only as a starting point. In the Baroque era, this measure was not used as the metronome had not been invented (Dahlhaus and H. H. Eggebrecht, 1983). Therefore, I decided to not specify a tempo, as is customary with wind instrument arrangements. In addition, as Donington (1978) puts it, I refrained from tempo markings to let the performer find an individual tempo based on the musical material and the type of dance. Harnoncourt (1988) and Donington (1978) underline that tempo markings in beats per minute do not consider the decisive importance of the sound environment. In a similar way to breathing and dynamics, I decided to not specify this element either because it would have been neither practical nor authentic.

Closing Remarks

In the bassoon literature, the bassoon transcription of Bach’s Cello Suites and Telemann’s Fantasias is unique. I created it with the goal of providing interested musicians with a version which corresponds to Donington’s definition:

“Performing editions. These may be based either on new scholarship or on existing scholar’s editions. They should give a precise reference to the source or sources used. Their function is to provide a practical text, without comment, but with adequate assistance to the performer” (Donington, 1978, p.24).

With this in mind, unlike previous transcriptions, I devoted elevated attention to preserved manuscripts, critical editions, and the performance practice of the period, which were all incorporated in the notation of the transcribed sheet music in the way I described it in this study. I sincerely hope that the consistent and unambiguous score helps anyone who is interested, including prospective bassoonists (especially those in higher education), fellow instructors, and performers, who I believe can create their own version now better than ever before if they rely on my transcription.

References

- Banda, E. (1993, ed.): Bach, Johann Sebastian: Sechs Suiten für Violoncello allein. BWV 1007-1012. Edito Musica, Budapest.

- Beisswenger, K. (2000, ed.): Bach, Johann Sebastian: Sechs Suiten für Violoncello solo. BWV 1007-1012. Breitkopf & Hartel, Wiesbaden.

- Beyer, M. & Brown, R. (2013, eds.): Telemann, Georg Philipp: Zwölf Fantasien für Flöte solo TWV 40:2-13. G. Henle Verlag, Munich.

- Béthizy, Jean – Laurent de (1754): Exposition de la théorie et de la pratique de la musique. Paris. Facsimile: 1972. Edition Minkoff.

- C. Dalhaus, H.s. Heinrich Eggebrecht (1983-85, eds.): Brockhaus-Riemann Zenei lexikon I-III [Musical Encyclopaedia I-III]. (Editor of the Hungarian edition: Boronkay Antal), Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Donington, Robert (1978): A barokk zene előadásmódja [A Performer’s Guide to Baroque Music]. Hungarian translation: Karasszon Dezső. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Dörffel, A. (1895, ed.): Bach-Gesellschaft Ausgabe. Band 45.1 Plate B.W. XLV (1). Clavierbüchline für Wilhelm Friedemann Bach. Breitkopf und Härtel, Leipzig.

- Fuchs, J. R. (1985, ed.): Tübinger Beiträge zur Musikwissenschaft. Vol. 10. Studien zu Artikulationsangaben in Orgel- und Clavierwerken von Joh. Seb. Bach. Hänssler-Verlag, Neuhausen-Stuttgart.

- Gallois, Pascal (2009): The Techniques of Bassoon Playing. Bärenreiter-Verlag, Kassel.

- Harnoncourt, Nikolaus (1988): A beszédszerű zene [Music as Speech]. Hungarian translation: Péteri Judit. Editio Musica, Budapest.

- Hirschmann, W. – Nastasi, M. (1999, eds.): Telemann, Georg Philipp: Fantasien für Flöte solo TWV 40:2-13. Wiener Urtext Edition, Schott/Universal Edition, Mainz und Wien.

- Kuijken, B. (1987, ed.): Telemann, Georg Philipp: Fantasies for Flute solo TWV 40:2-13. Musica Rara, Monteux.

- Leisinger, U. (2000, ed.): Bach, Johann Sebastian: Suiten für Violoncello solo. BWV 1007-1012. Wiener Urtext Edition, Schott/Universal Edition, Mainz und Wien.

- Mattheson, Johann (1713): Das neu – eröffnete Orchestre. Hamburg. Facsimile: Laaber-Verlag, Regensburg.

- Mozart, Leopold (1998): Hegedűiskola [Gründliche Violinschule]. Hungarian translation: Székely András. Mágus Kiadó, Budapest.

- Oromszegi, Ottó (2003): A fagott. Eredet- és fejlődéstörténet. The author's own release. Budapest.

- Quantz, Johann Joachim (2011): Fuvolaiskola [Versuch einer Anweisung, die Flöte traversiere zu spielen]. Hungarian translation: Székely András. Argumentum Kiadó, Budapest.

- Schwemer, B. & Woodfull-Harris, D. (2000, ed.): Bach, Johann Sebastian: 6 Suites a Violoncello Solo senza Basso. BWV 1007-1012. Bärenreiter-Verlag, Kassel.

- Voss, E. & Ginzel R. (2007, eds.): Bach, Johann Sebastian: Sechs Suiten. Violoncello Solo. BWV 1007-1012. G. Henle Verlag, Munich.

- Walther, Johann Gottfried (1732): Musikalisches Lexikon oder musikalische Bibliothek. Wolfgang Deer, Leipzig.

- Waterhouse, W. (2003, ed.): Yehudi Menuhin Music Guides. Vol. 1. The Bassoon. Kahn & Averill, London.

- Weisberg, A. (2011, ed.): Bach, Johann Sebastian: Five Suites for Solo Bassoon. BWV 1007-1011. Ludwig Masters, Boca Raton.

- Wolff, Christoph (2009): Johann Sebastian Bach. A tudós zeneszerző [Johann Sebastian Bach: The Learned Musician]. Hungarian translation: Széky János. Park Könyvkiadó, Budapest.

[1] The transposed keys for further Telemann Fantasias: No.1 from A major to C major, No.2 from a minor to c minor, No.3 from b minor to d minor, No.6 from d minor to f minor, No.7 from D major to F major, No.8 from e minor to g minor, No.9 from E major to G major, No.10 from f-sharp minor to a minor, No.11 to G major to B-flat major.