Author: Ágnes Török

DOI: 10.5434/9789634902263/3

Abstract

The Avant garde schools required a notation style different from the traditional one both in instrumental and vocal music. This study points to the historical background of contemporary notation and the interdependence of the graphic representation of sound and notation. The illustrations are primarily quotes selected from the Hungarian choir literature and further material is used to introduce the authentic elements used for modes of expression.

Key words: choral music, contemporary musical notation, graphic elements, chance

Historical Background

Fixed rhythm and exact pitch notation have not always been prerequisitives in the history of music, as certain stylistic elements and the performance relying on conventions rather than the musical notation did not necessitate them.

Male singers educated in the scola memorized hundreds of Gregorian melodies, so in the everyday liturgical practice they easily remembered the melody with the help of the chantor’s conducting movements. That is why there was no need for the exact notation of the early Gregorian melodies; illustrating the conducting movements, that is the neuma, was enough.

The free performance style of the Gregorian music does not require the exact rhythm and tempo notation, either. Recitation adapts to the accent of Latin and metrical rhymes are known. Singers often loosed the strict rules of metric rhymes with melismas, which they could use without restricitons. Despite of the fact that certain marks and Latin letters were attached to the neumas to illustrate the exact melody and the rhythm, neuma writing remained still suggestive rather than defining.

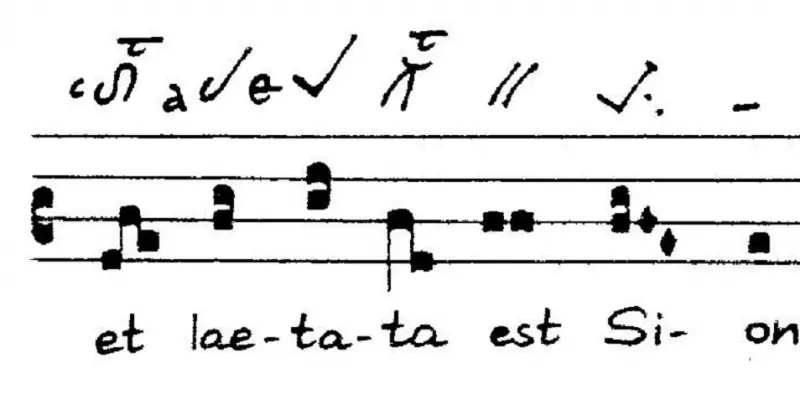

The below neuma groups from the introitus starting as ”Adorate Deum omnes Angeli eius” (Graduale Triplex 264) define the tempo and character of the melody quity precisely, but they only refer to the pitch.

From the introitus starting as ”Adorate Deum omnes Angeli eius”

If we interpret the shape of the marks as conducting movements, the performance will be sensitive and free. For instance, we have to differentiate two illustrations of the second: the angled, slower pes and the round, faster pes.

![]()

![]()

Two identical notes on one syllable can not be merged even if we have two separate virgas (Cardine 27):

![]()

The character of the performance is indicated by letters:

celeriter = playfully, lively ![]()

tenete = long, sustained ![]()

Letter signs indicating the pitch:

altius = higher ![]()

aequaliter = same ![]()

The beauty of the quote is the ending: the higher pitch of the angled, slower pes is prolonged with an episema, two sloping punctums and a calm closure. In a couple of centuries later, the slow-down is indicated by the simple rit.

![]()

There are a lot of similarities between the form of the Gregorian neumas and the graphic notation of contemporary music. However, while in the Middle Ages they did not know how to register certain elements, in the 20th century they did not want to register them.

The turning points in the history of musical notation can be linked with the birth of new compositional techniques, among which three significant changes should be mentioned:

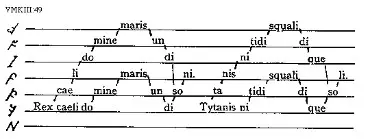

The first change was triggered by the birth of polyphony in about 900. The first surviving treatise that discusses polyphony, the Musica Enchiriadis, illustrates the pitch by placing text onto the spaces of second interval in the staff. The 18 dasia marks defined the pitch and the place of the major (tonus) and minor seconds (semitonus) in the melody (Musica Enchiriadis). However, this method can be used only for noting down two lines, a new notational technique needed to be invented for registering multiple lines simultaneously.

1. The ”Rex coeli Domine organum” from the Musica Enchiriadis

2. Dasia marks

2. Dasia marks

The question of how to mark the pitch was solved much earlier than the question of how to note down the rhythm. The graphics of the Gregorian neumas and neuma groups defined the performance quite strictly, but the final solution of how to mark the pitch precisely was brought by Arezzoi Guido’s (991/992-1033/1050) technique. He started to note down the pitch in third spaces and his technique has been used up until today (Gülke 69).

The modal notaiton associated with the school of Notre Dame aimed to note down different rhythm types. The modal notation linked the rhythmic patterns of the Greek versification to the liturgy, and it defined the length of the notes based on their place in the liturgy. Accordingly, six rhythmic patterns could be defined based on the metric versification. This method could be used in practice only until the musical style of the Middle Ages changed.

The composers’ inventiveness and creativiy depend on two factors: the technique of exact pitch and free rhythm notation needed to be developed. The rhythm patterns based on the Greek versification ars antiqua did not provide many possibilities. While the vertical illustration of the pitch in staff notation got realized in the eleventh century, the illustration of free rhythm was yet to be invented in the fourteenth century. It was Ph. de Vitry, who illustrated the length of a note by using graphic and mathematical methods: he marked the rhythmic duration with notes of different forms and he set up a mathematical correlation between them (Gülke 179). Some other graphic amendments were created in the centuries following ars nova, but Ph. de Vitry’s idea has remained significant in the Western-European music up until today.

The Instrumental Avant-garde Music and Its Notation

In 1906 Feruccio Busoni (1866-1924) writes the following about the traditional musical instruments in his Sketch of a New Aethetics of Music (Abbozzo di una nuova estetica della musica):

“If music has to take off conventions and froms like a shabby cloth, it is hindered primarily by today’s musical instruments. Musical instruments are bound to their voice of range, their sounding capabilities, and the peformer is also limited by these boundaries.” (Ignácz and Kertész)

Apart from criticizing the traditional sound, Busoni was planning to design instruments that are capable of sounding the smallest pitch differences. In connection with this he was also concerned with the further possibilities of the seven-tone system: ”The aim is the abstract note, the unhampered technique and the unlimited atonal raw material” (Haraszti). It is important to note that there is no connection between Busoni’s atonal sound ideal and the Viennese atonalists: they have different aims and means to reach them.

Luigi Russolo (1885-1947), painter with an interest in music, similarly to Busoni, claimed that the classical sound of instruments is obsolete. According to the manifesto ”Art of Noise” (L’Arte dei rumori) published in 1913 by Russolo and other futurist artists, applying noise is the ”logical consequence of a marvelous innovation.” The noise made by the machines of the ninteenth century, the new industrial environment, the city and all the noises around the people are the source of beauty. Only the noise-sound is capable of breaking through the barriers of the musical note, since, contrary to the regulated vibration of the note, noise is rich in semitones and tonal characters. In his manifesto Russolo does not expect the noises to be represented in their sheer form but he considers the physical features of the noise to be the ”abstract material” of the piece of art.

In order to put his aesthetical views into practice, Russolo created his noise-intonators (intonarumori) and he presented them on so-called noise-concerts: 1. roars, claps, noises of falling water, driving noises, bellows, 2. whistles, snores, snorts, 3. whispers, mutterings rustlings, grumbles, grunts gurgles, 4. shrill sounds, cracks, buzzings, jingles, shuffl es, 5. percussive noises using metal, wood, skin, stone, baked earth, etc., 6. animal and human voices: shouts, moans, screams, laughter, rattlings, sobs.

Russolo’s pieces were played on noise instruments, such as buzzers, gurglers, bursters, shatterers, thunderers, shrillers, whistlers, snorters and rustlers (Ignácz and Kertész).

The common point in Russolo’s and Busoni’s aesthetics is the notion of creating the abstract sound. While Busoni aims to realize it in a theoretical way by dividing the intervals on a micro level, Russolo applies noises as tone colours in practice.

The futurist musical aesthetics had only few followers, but the movement had significant impact. It influenced the art of Edgar Varèse and John Cage, Stravinsky enthused and gushed over it, the new musical instruments were considered to be the most revolutionary orchestral discovery (Ignácz and Kertész).

John Cage (1912-1992) is one of the most influential experimentalists of the new music. In his pieces he moves away from the classical compositional techniques and he aims to eliminate organization completely. The melodical, harmonic, tonal or structural cohesive force is replaced by the unrepeatable and circumstantial. He uses the spots on the paper, the drawing of constallations or sematic graphics to subvert the conventional sound and form. These graphic ”notations” define only the time-frame, depict the structure and the process, but they do not mark the pitch, the rhythm or the form. The composer lets the performer interpret the drawing for him- or herself.

Cage manipulates the sound of the piano by placing different obejcts among the strings. In this way the emerging noises and unfamiliar harmonic colours cancel all melodical and harmonic relations. A paradigma change happens in interpreting the notes: Cage focuses on the notes’ physical aspects and not on their functional quality. The ”prepared piano”, the instrument that alienates the sound, could be seen as the symbol of the ”new music” era.

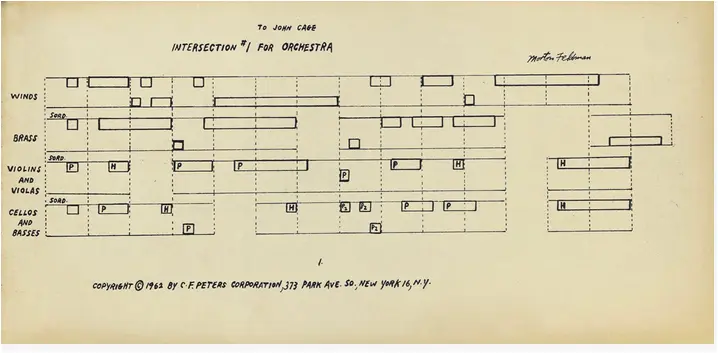

Morton Feldman (1926-1987) does not mark exact notes and fixed rhythm, he only gives general instructions about the register and the number of notes played in the given unit of time. By letting the performer choose the pitch and the rhythm, the composer loosens the connection between the composer and the composition completely (Copland 208-213).

”Then, if this was the ’experimental music, what was the experimentum?”. The recurring question of ”what else music can be?” and the exploration of what can make us experiment certain things as music. We have come to the conclusion that music does not necessarily need to have rhytm, melody, harmony, structure, not even notes; it does not need to imply instruments, musicians or unique locations. It has become accepted that music does not require organized notes or a certain structure, isntead, music goes through an interpretative process that we, the audience, are able to control. Music moves from the ”outside” to the ”inside”. If the experimental music has a message, this is it: music is something created by the mind”. (Nyman 9)

Acoustic engineering started to develop from the 1930s and it opened up new perspectives for those who interpreted the musical sound in a wider sense. The first live electronic music was the first movement of Cage’s ”Imaginery Landscape” from 1939. At the beginning acoustic engineering helped only in registering or amplifying music, in the fifties it gave numerous possibilities for experimentation: sound distortion, use of the full frequency range, division of half-notes, merge of different musical dimensions, mix of tonal qualities, complete freedom of intonation and rhythm, prerecorded sounds from the nature etc… With the electronic musical instruments and the modern acoustic engineering the new notion of ’concrete music’ was born. From the perspective of how noise and sound are used, the electronic musical experiments take two directions. The sounds of our everyday environment (musique concrète) or the electronically generated sounds (elektronische Musik): the German or the French way.

Pierre Schaeffer (1910-1995) selected and recorded sounds from the nature and played them backwards. It is an interesting technical move, but only an experiment (Salzman 178-200).

Karlheinz Stockhausen’s (1928-2007) art is defined by the inexhaustible world of the electro acoustic instruments. There are endless possibilities to manipulate the sounds, while the sinus tones free from half-notes and the complete lack of connection with the performer make the performance rigid and monotonous. This impersonal feeling can be less prominent in pieces composed for audio tape and certain performers. For instance, his work ”Kontakte” was composed for electronic sound, piano and percussions (Copland 208-213).

We can adopt traditional notation for the works that are based on aleatoric methods (the circumstantial) only partly or not at all. The classical staff, the notes, the rhythmic value and the clefs help the composer to note down his or her work as precisely as possible, but they also expect some creativity form the performer. There are some references to the dynamics and the tempo, but they are not binding. The mode of expression is requested only in a general written form, artistic performance is determined by the artist. In this way the performer plays a mediatory role between the composer and the audience. The works noted down with classical notation can be performed many times, difference can only be in the performer’s style and mode of expression.

How can we note down a piece of music that rejects all traditonal concepts? How can we note down free form and style? How can we note down the composer’s intent if the decisions are handed over to the performer?

They had to find another way to note down noise effects, prosaic parts and the circumstantial. Electronic recording can be a solution, but we lose the performance’s randomness and there is no need for a performer, who communicates between the composer and the audience.

The only solution was for the composers to find their own ntoational technique. As each musical composition is an experimentum, a general symbolic system can not be formed. Each and every piece of art has a unique system of signs that offers a unique explanation. These separate explanations also point out to the fact that these experiments could not create a common style and a consensual notational technique.

Cage composed his piano work Music of changes (1951) based Ching I’s sacred book, which explains the inevitable connectedness of symbols and the world and had an influence on confucianism, as well. He explains the seemingly traditional but rather packed and complicated notation on a separate page. For instance, the numbers of bigger size (3·5·6 3/4·5·3 1/8) indicate tempo change, the unit of time is determined in centimeter (2 ½ cm= h), the beginning of a sound is indicated by the stem of the note and not its value (John Cage Complete Works).

3. From J. Cage’s piece of music for the piano Music of Changes

3. From J. Cage’s piece of music for the piano Music of Changes

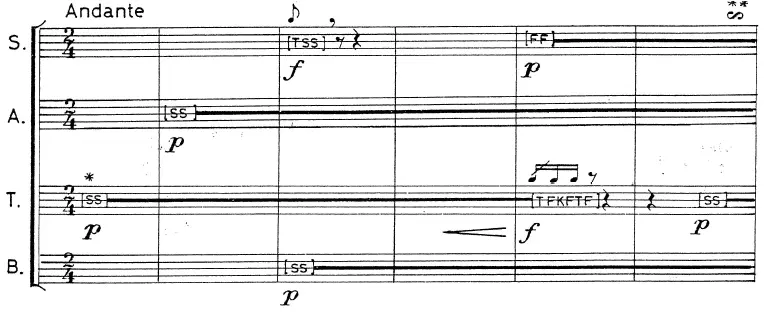

Feldman’s first graphic composition for full orchestra is Intersection 1 (1951). He recommends the work for Cage and he explains its way of reading in an explanatory key. Each head is a unit of time of equal length, determined by the performers. The smaller quadrangles placed in the heads indicate only the pitch; the dynamics and the rhythm are free.

4. Extraxt, from Felmand’s orchestral work Intersection I.

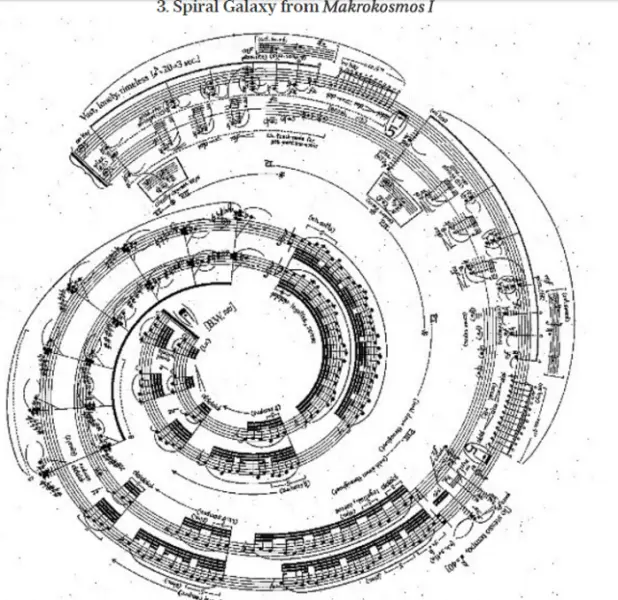

Georg Crumb (1929)’s piano cycle Makrokosmos (1972; 1979) was inspired by Bartók’s Mikrokozmosz. The notation can be read in the traditional way, but the graphics depict the title of the movement visually:” Spiral Galaxy”.

5. G. Crumb: Spiral Galaxy (from piano cycle Makrokosmos)

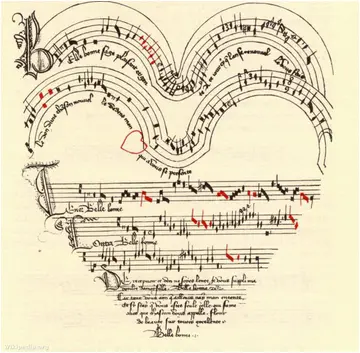

The similar ”eye music” notation is not a new idea in the history of music. A couple of beautiful Renaissance notations have subsisted, which are mainly for ’the eye’, their melodies reflect the musical trend of the era.

6. Baude Cordier’s Belle, Bonne, sage

Avant-garde Endeavours in the Vocal Music

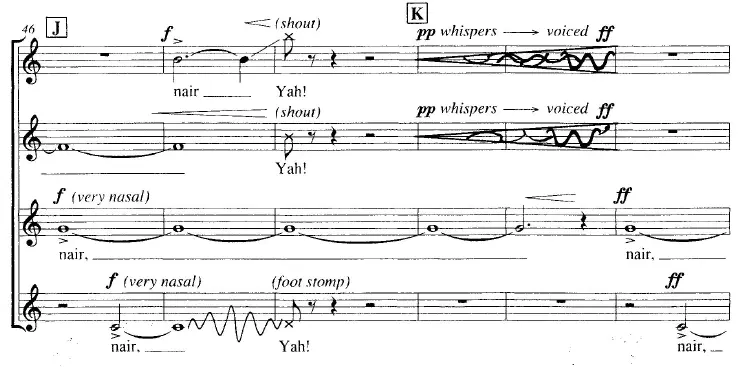

The practice, or rather, experiment of manipulating the sound appears not only in works that are written for classical or eletronic musical instruments but also in works that are written for the human voice. The composer considers the musical instrument and the human voice as an unified corpus making sound. The musical instruments and the human body define natural boundaries, but the vocal and instrumental works move away from the traditional tools of expression and interpretation.

In the vocal, especially in the choral works the avant-garde instrumental innovations appear moderately, rather as effects and not as stylistic elements. Certain composers experiment with works, in which the human voice does not appear in its conventional sense, but their number is rather scarce.

The most important goal, that is to break with predefined structuralism, could not be realized as the majority of vocal music is based on texts. All texts have cohesive forces: structure and rhythm. The melodic and harmonic attraction can be loosed, dynamic building can be changed with static state, but the cohesive force of the text will remain, even if to a different extent. The mediaeval music is also static: there is no functional harmonic attraction, the form is defined by the grammatical articulation of the Latin text, the modal melodies and the fixed formula of the rhythmic patterns have no dynamic cohesive force. This kind of static feature, however, is a state, a stylistic sign and not a goal.

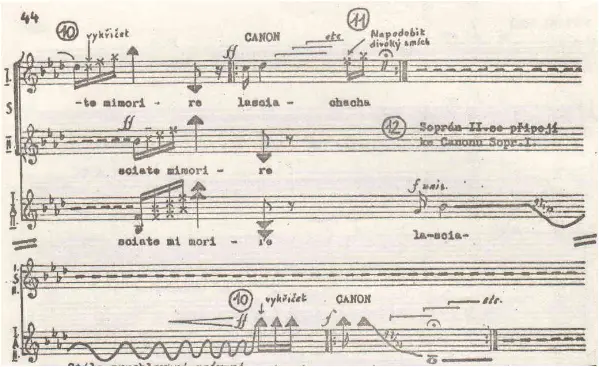

Although it is not possible to eliminate structuralism completely in vocal music, the composers maximize the vocal possibilities. Extending the ambitus as much as possible, intonational difficulties, prosaic elements, emotional sound effects, eliminating the usual cohesive forces (rhythm, melody, part-writing, harmonies, attraction between sounds) are all part of their means of expression.

The different sounds, even if out of tune, colours, noises that are played on musical instruments open up many possibilites for the composers, but the human voice and body provide limited possibilities. The instrumental range can be used from the great octave up to the thrice-accented octave, sounding the special colours depends on the player’s technical skills. The human voice range has two octaves, its colour and dynamics vary from person to person. Besides, the human voice implies unusual leaps, a twelve-note scale and intonational problems coming from the insecure tonality. The seven-tone system is complemented with packed alterations, which connect numerous micro-tonalities, so, in this case, the frequent tonality changes can be problematic. In the vocal music the twelve-note system can cause problems not only as the means of atonality but as alteration, moreover, the horizontal intonation is influenced and disturbed by the ”distracting” force of simultaneous sonority. Besides the intonation, the timbre and the range of voice, it is important for the singer to have good performance skills, as he or she has to convey the musical message through his or her own body without the help of a mediatory instrument.

After listing all these exclusive factors the question emerges: what other possibilities do we have? The answer to the question must clarify that the principles and tools are the same in the instrumental and the vocal music, but in the choral literature these can be realized only within certain limits.

- The use of the ”unpredictable” abandons the strict rules of intonation and rhythm. The request for indefinite pitch, improvization or improvizational effect, avoiding simultaneous sonority, free timing of each form etc.. are all part of the means of expression.

- Vocal timbre range can be extended by adopting prosaic elements, changing the colour of the vocal timbre, by the expressive depiction of extreme emotional states and by onomatopoeia.

- The appearance of everyday sounds in music extends the classical interpretation of sound: it considers not only the vocal cord but the whole human body a sound-producing organ.: clap, snap, stamp, shout, even yawn and laughter etc.

The Notation of the Avant-garde Elements of Choral Music

In the Avant-garde art aleatoricism, that is the incorporation of ’chance’, can be found primarily in the instrumental music but it can be found occasionally in choral music, as well. ’Chance’ does not mean a sound played by accident or a mistake made by the performer. ’Chance’ is an event planned by the composer to serve the expression. It does not appear in the musical notation, only in the composer’s instructions, which contain constant and variable elements. For instance, while tonal domain can be defined as a constant element, rhythm and dynamics can depend on a sudden decision made at the time of the performance. Dynamics can be a constant element but pitch is determined by the performer at the time of the performance etc.

Notational techniques imply the freedom of interpretation and the possibility of improvisation. It requires the performer to have a certain level of improvisatinal skills - or at least some courage - to realize what the composer imagined.

The musician’s creative instinct has always played an important role in the solo works. We can think of numerous examples, from folk music to jazz, from the realized continuo to noting down classical cadency. In all cases improvisation has a decorative function, it shows the performer’s stylistic expertise and technical virtuosity. In the twentieth and twenty-fist century, however, there are several various tendencies, from the experimental works to the comletely unique style. Improvisation does not rely on general stylistic elements any more, which can be used and elaborated by the performer. Performers are given full authority to experiment and they become co-composers at the moment of performance.

In the choral literature, unlike instrumental and solo vocal works, we can barely find aleatoricism. There are some aleatoric choral pieces of music, but they are rather performance than choral works. Many times these works include movement, perhaps means of expression used by other branches of art, and they transform into a stage event (Salzman 245).

And the reason why so few aleatoric choral works are composed is simple. On the one hand, it is important for both the composers and the performers to remain authentic to the content of the text, for which the traditional means of expression are enough. On the other hand, the choir is a harmonized instrument, an organism. This harmonism can be ensured only by one of the following: defined rhythm, melody or tempo. The individual improvisation of each choir member is viable only if improvisation is conifned by fixed elements and is allowed only in certain phases or formal units.

While the classical notational technique is perfectly adequate and enough to note down concrete musical elements, there are no graphic signs to depict improvisatory parts and unpredictable sounds. Compared to instrumental music, choir music contains fewer non-conventional elements, so besides individual notation, a standard, understandable system of signs evolved.

Present thesis follows the standard categorization of contemporary notation in musical literature but notes that in practice we can not draw a clear line between the different notational techniques (Mabry). The selected excerpts present only a couple of typical forms, it is the performer’s task to study and interpret the whole musical notation.

The Indicative Notation

The indicative notation can contain fixed or free elements, but it does not confine the singers’ performance. This technique does not use metre, it relies on sense of rhythm and tempo. The depiction of rhythmic value, pitch, tempo, dynamics and mode of expression look more like graphic rather than musical notation. Many times an explanatory text is attached to the signs.

Most common forms:

a) frame

b) lines, arrows

c) note heads and forms without rhythm

a. Frame

Motive repetation in a given rhythm, in defined or free tempo:

Motive repetition in free rhythm and free tempo:

The notation of free rhythm, pitch, dynamics and tempo in this mode implies freedom and exact requirements at the same time. Within the frame we can find improvisatory elements, while outside the frame we can find verbal or other traditionally defined exact instructions. The performer, first of all, needs to decipher what effect the composer wants to make with the content of the frame, then he needs to harmonize the momentary performance with the actual instructions.

Arne Mellnäs (1933-2002): Bossa Buffa

The text cites Cicero: ”Nemo saltat sobrius, nisi forte insanit” (”Almost nobody dances sober, unless, of course, he is mad”). The title also refers to the quote: Bossa Buffa (The Ludicrous Jug).

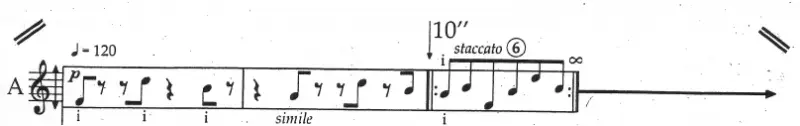

The two end points of the vertical arrow defines the range of the alto part: d’-g”. The notes within the frame move in an exactly defined rhythm, dynamics, tempo and sounding range, the pitch is only approximate, it remains within the range of the frame. After the two relatively fast metres, we have similar material for 10 seconds. The sign ∞ above the repeat mark refers to an undefinable number of repetitions and not to the time duration. The 10” is obviously not an exact time unit, it is rather a sensation created by the momentary musical process. The circled number is the composer’s instruction: in the beginning we can diverge from the basic rhythm only slightly, as if we were singing wrong: ”The first time only slight divergence from the basic rhythm (as in ’singing wrong’)”.

7. Arne Mellnäs: Bossa Buffa (1973)

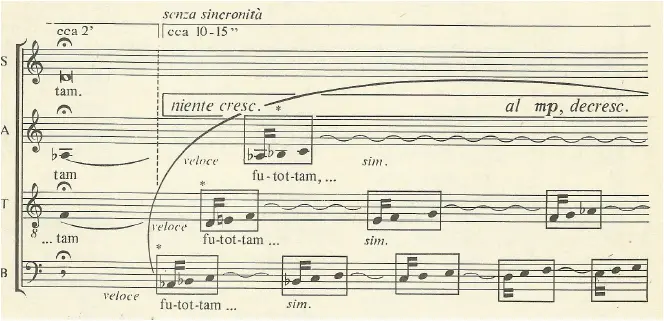

György Orbán (1947*): Madrigal

In the mixed choir covering ”Grief” by Attila József the chased deer sprouts up out of nowhere and appears as a distant image. This impression is created by the senza sincronitá sounding of the notes within the frame lasting for about 10-15” and in the starting and ending points of the dynamics. At first sight we might believe the conent of the frame can be interpreted freely, but the composer’s instructions (*) about the dynamics and the tempo, the long connecting ligature, the sensibly selected notions (niente, veloce, sincronitá) define the mode of performance precisely: *”Parts need to enter one-by-one, independently. in independent rhythm, growing from nothing (niente!). Clear intonation is crucial. In the same way, the whole has to disappear into nothing. Lower sounds (basses!) must be handled accordingly (Orbán).”

The word ”futottam” (I was running) has fixed notes as well as fixed rhythm. The composer expects the word to be sung in the right rhythm

(ᴗ - -), even if he does not mark it in the traditional way.

8. György Orbán: Madrigal (1982-1983)

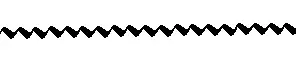

b. Lines, arrows

The musical material preceeding the wavy line can be repeated freely.

The musical material preceeding the wavy line can be repeated freely.

![]() The musical material can be repeated higher and higher, freely.

The musical material can be repeated higher and higher, freely.

The musical material can be repeated lower and lower freely.

The musical material can be repeated lower and lower freely.

Vibrato

Vibrato

Glissando

Glissando

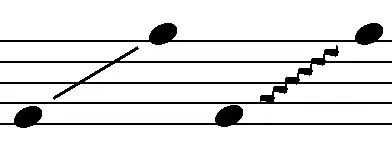

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937): Trois Chansons / Nikolet

The technique of glissando to connect two distant notes has already been used earlier. While Liszt used it as an impressive element in his piano works, in jazz it is used as a stylistic element.

The extract is an early example for the use of glissando in choral works. The topic of the first movement of the cycle is Nikolet, who, while searching for her husband, meets the wolf, the pretty young man and the old but rich man on the meadow. Ravel introduces the different characters magnificently, e.g. the young man, whose fastidious gestures are depicted through the technique of glissando.

Maurice Ravel: Trois Chansons/Nikolet (1915)

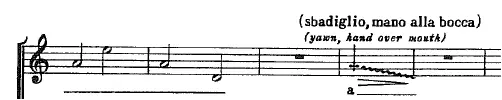

Goffredo Petrassi (1904-2003): Nonsense

The third movement depicts the bored, self-pitying man, who spends his days yawning. The instruction ”sbadiglio, mano alla bocca” written above the soprano part enhances the effect of the glissando and makes the situation ridiculous immediately.

Goffredo Petrassi: Nonsense/III. (1952)

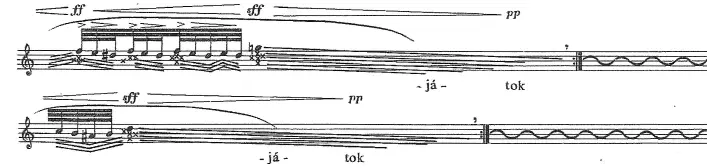

Zsolt Durkó (1934-1997): Necrology

In the oratory the fixed soprano is accompanied by lower female parts, whose movement is similar but their pitch is not determined. After the mixture-like glissando the hashness of the sff dissolves in pp.

Zsolt Durkó: Necrology (1972)

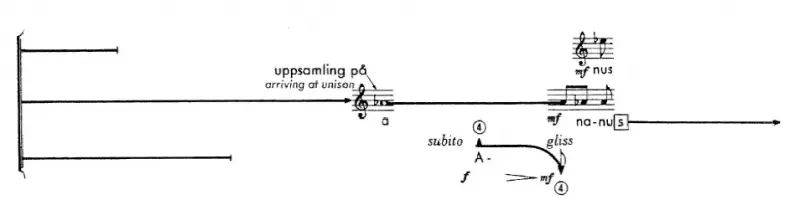

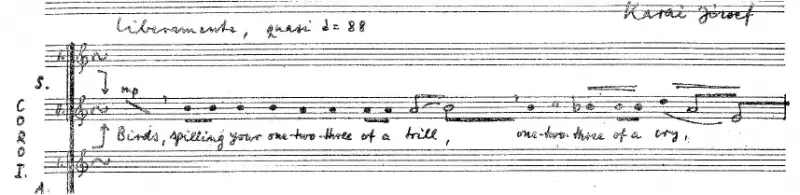

József Karai (1927-2003): Night

The women’s choir full of impressionist sensations sets to music Zsuzsa Beney’s poem. The composer’s instruction: ”the slower, moderate and faster simultaneous repetition of the marked notes until the end of the wavy line” In the third metre the alto part maintains the actual melodic motion but from the forth metre it is moving higher and higher.

József Karai: Night (1976)

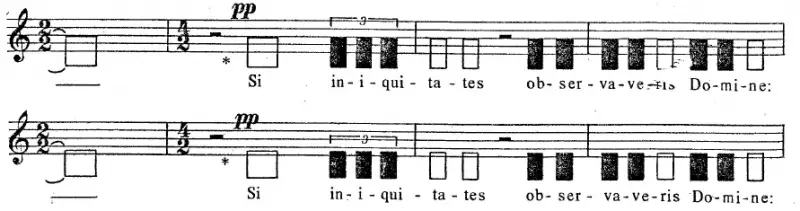

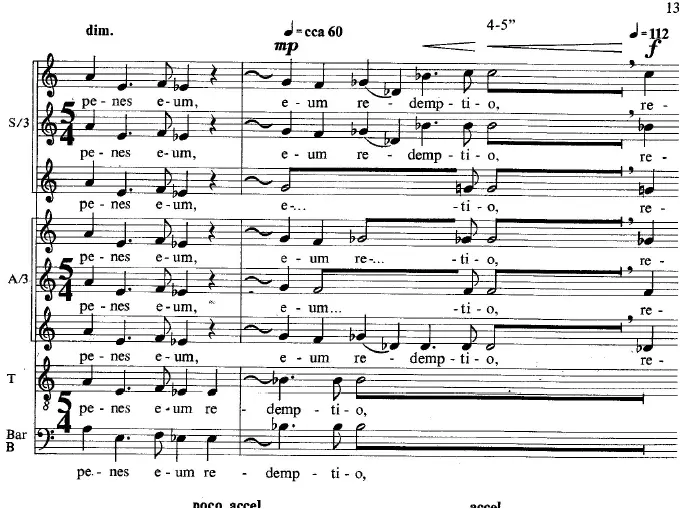

József Karai (1927-2003): De profundis

The lyrics is a quote from the Psalm 130: (-…et omnibus) iniquitatibus eius. The whole verse in English translation: ”He himself will redeem Israel from all their sins”. The notion of sin and redemption is depicted by dissonance and resolution. The 12-14-minute faster and faster chromatic material of each part is gradually purifying into a C major chord. Thanks to the free tempo and rhythm, the notes of the ”chaos” preceeding the C major pause sound at the same time in practice. The sounds of the following solos fall into the depths.

József Karai: De profundis (1984)

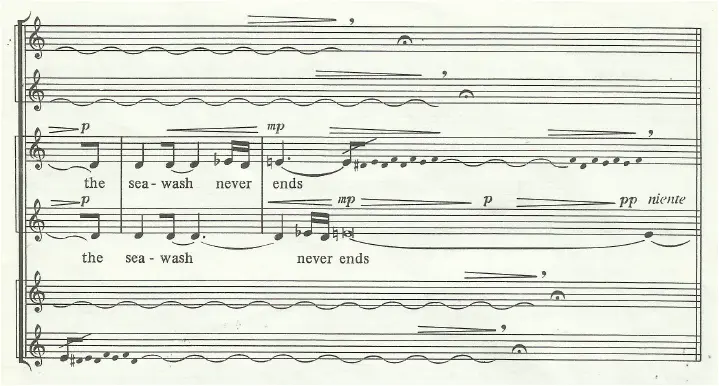

Miklós Kocsár (1933-2019): Sea-wash

The free repetition and gradual disappearance of the rhythmless motive illustrates the eternal waving of the sea (”sea-wash never ends”). It might not be an accident that the composer chose the waves, but the visual effect speaks for itself:

Miklós Kocsár: Six Choruses for Female Choir to poems by C. Sandburg / Sea-wash (1982)

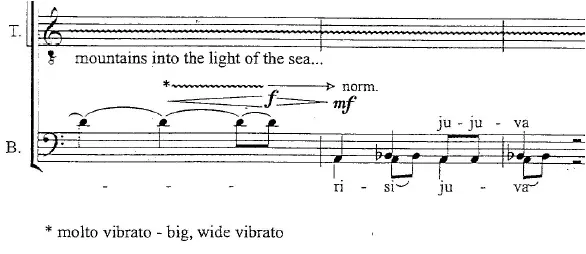

Sommereyns Gwendolyn (1982*): Poor Corydon

The composer requires vibrato with wide amplitude from the bass. After the dynamic culmination he returns to the natural sound generation gradually, the process of which he illustrates with a wavy line transforming into an arrow.

Sommereyns Gwendolyn: Poor Corydon (2005)

c. Without note heads or fixed rhythm

|

|

In fixed rhythm, free pitch (can be linked to register, too). |

|

|

Declaimed in fixed rhythm. |

|

|

Fixed pitch in free rhythm. |

|

|

Cluster linked to register not to pitch. |

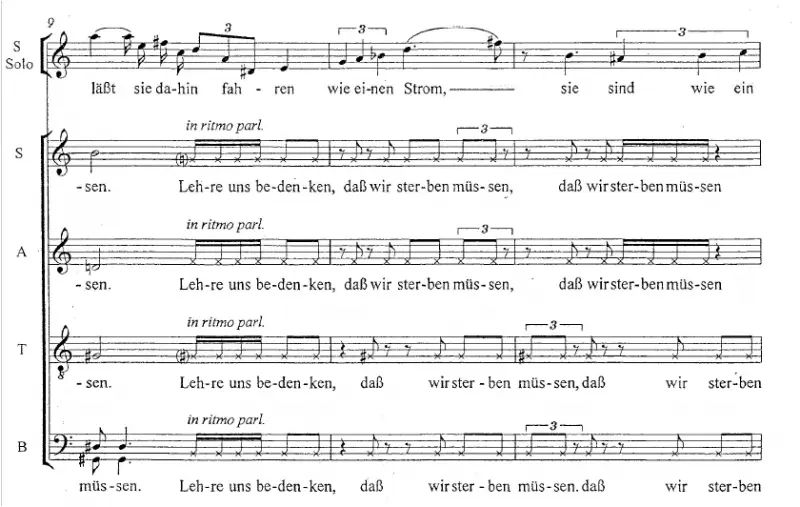

Arnold Schönberg (1874-1951): Pierrot Lunaire

In the eighteenth-century France in some of the scenes of the prosaic plays the actors’ performance was accomanied by background music to create a more dramatic effect. The new genre of melodrama was first represented by Rousseau’s Pigmalion (1762), later by Franz Liszt’s Der blinde Sänger. The lyrics is very expressive, the performance is overly declamatory, so later on melodrama means a manner of performance rather than a genre. Franz Liszt wrote the lyrics above the piano part and left the mode of expression to the performer.

Franz Liszt: Der blinde Sänger (1875)

In the twentieth-century vocal music speechsong (sprechgesang) is a major stylistic element, clearly distinguished from recitation. While the notation of the speechsong is linked to the exact pitch, the spoken or half-sung reciting notes are noted with various graphics.

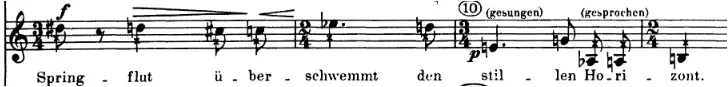

Arnold Schönberg uses melodramatic stylistic elements as well, but not in the original, sentimental manner. He strives for complete expressivity in the relation between the lyrics and the music. The notation of Pierrot Lunaire has exact pitch-notation, but the stems of the notes are crossed with an X-stroke. He barely uses vocal sound and distinguishes ”gesprochen” and ”gesungen” performance:

Arnold Schönberg: Pierrot Lunaire (1912)

Schönberg does not give exact intstructions about the performance, he just writes about the desired effect in the Introduction. The performer’s task is to transform the melody into a spoken melody. He or she needs to follow the rhythm, but not in a monotonous voice, and the performance can not resemble singing.

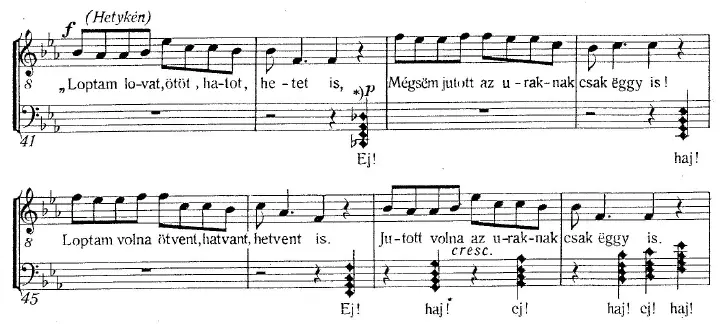

Zoltán Kodály (1882-1962): Songs from Karad

In the choral composition we can meet one of the early indicative pitch notation techniques of choral literature. Pista Kormos, who has stolen a horse, is escorted by gendarmes, whose reproving grumbling becomes threatening in a couple of metres: ”The square notes do not indicate real pitch, only murmur for several voices, whose ascension is in the indicated direction (Kodály 57)”.

Zoltán Kodály: Songs from Karad (1934)

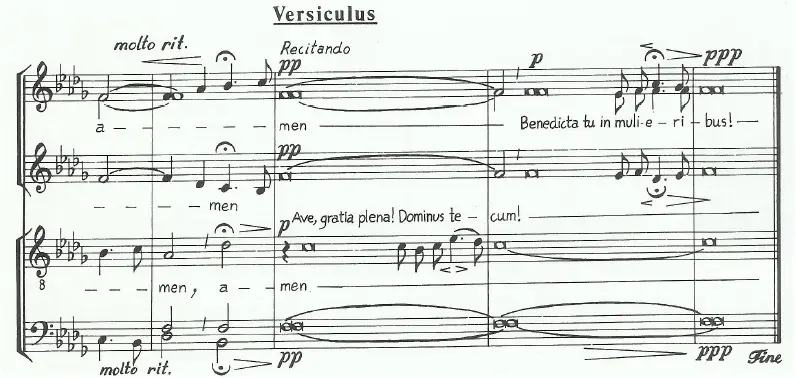

Trond Kverno (1945*): Ave maris stella

Recitation is the basic stylistic element of the gregorian music and it is used in Latin works several times. In his choral composition Kverno instructs the parts to recite in the work’s final stage. Recitation is important to be carried out in the same way as in the gregorian psalms, even if it is not instructed seperately by the notation.

Trond Kverno: Ave maris stella (1976)

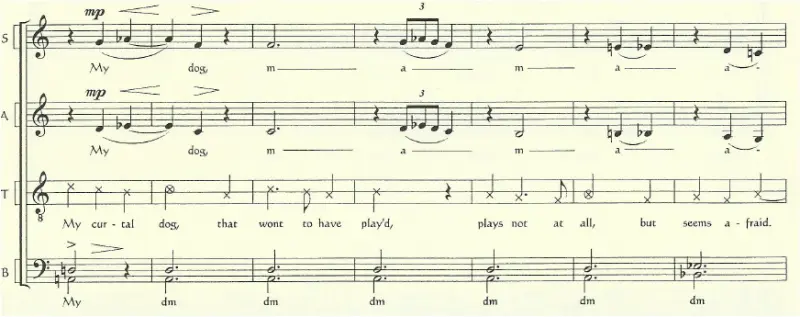

Sommereyns Gwendolyn (1982*): Poor Corydon

The schönberg solution is applied to mark speechsong later on, as well, but in the choir works it is possible only in short phases due to the character of the performing apparatus. Instead of the note heads, ’x’ is written but always within a rhythmic pattern. The stave has three lines and the distance between them suggests that, instead of the exact pitch, they mark the line, the rhythm and the accent relation of the declamation:

Sommereyns Gwendolyn: Poor Corydon (2005)

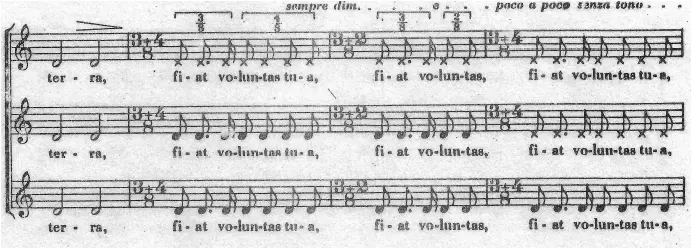

Bengt Johansson (1914-1989): Pater noster

The specific and ”senza tono” notes sound at the same time, then the recitation in the middle register is gradually taking over the role of the D note:

Bengt Johansson: Pater noster (1968)

Miklós Kocsár (1933-2019): Oh dawn, dawn

In the mixed choir based on the text of an archaic folk prayer, it is not allowed for the inner parts to recite at the same time, but it is advisable, although not necessary, to find certain meeting points between the outside parts.

Mikós Kocsár: Oh dawn, dawn (1993)

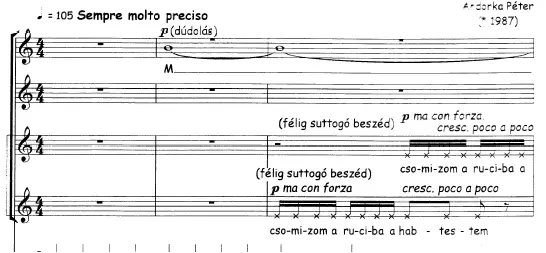

Péter Andorka (1987*): By accident

His work for women’s choir is based on János Lackfi’s poem that mocks colloquial language and its lower parts are repeated rhytmically, senza tono (”half-whispering speech”).

Andorka Péter: Véletlen (2017)

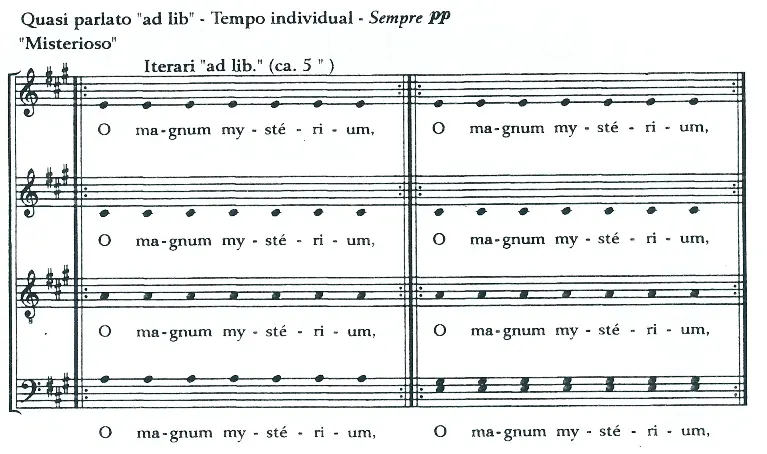

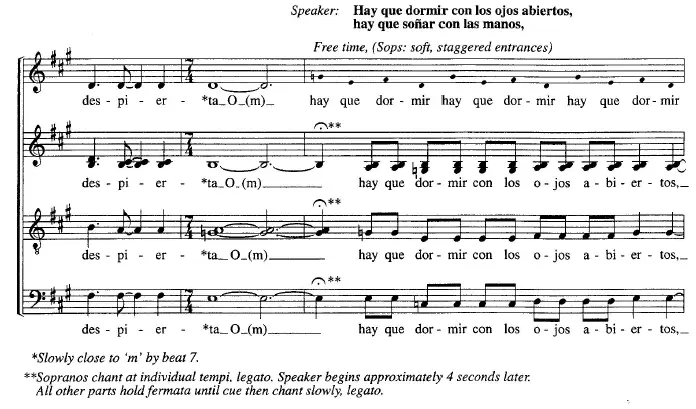

Javier Busto (1949*): O magnum Mysterium

In the beginning phase of the composition for about 5’’ the text of the responsory of the Christmas matutinum is repeated in an arbitary number of times (Iterari „ad lib”), in an arbitrary tempo (Tempo individual) and in a speechlike manner (Quasi parlato). The aim is to reach the ”misterioso” effect.

Javier Busto: O magnum Mysterium (1998)

Knut Nystedt (1915-2014): De profundis

One of the early means to loosen the classical chording and harmonic relations is the cluster: a group of notes at a second distance from each other sung at the same time. It does not have a functional role, but it does have a tonic note. In the first movement of Zoltán Kodály’s Mountain Nights the floating unison of the major seconds built on F has a decisive role. This colouring chord built on the idea of distancy is a tetrachord, but due to its scale-like development and its application as an organ point, we can call it a cluster.

Zoltán Kodály: Mountain Nights I. (1923)

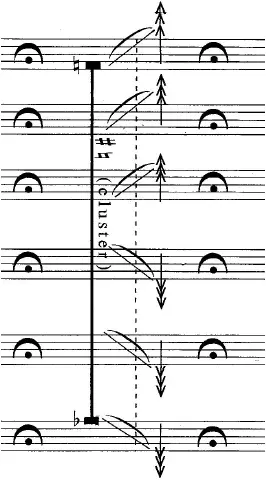

In Knut Nystedt’s work for mixed choir De profundis the group of notes with fixed pitch behaves as a cluster and in each psalm verse it alternates with the cluster noted down with arbitrary pitch within the given register.

Knut Nystedt: De profundis (1966)

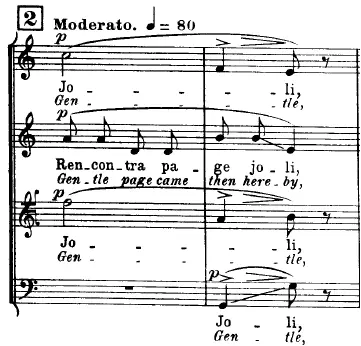

The Proportional Notation

Most common forms:

a) proportional distance

b) tempo notation of groups of notes

c) time axis

a. Proportional distance

|

|

Proportional illustration of the length the syllables |

József Karai (1927-2003): De profundis

The classical notation is proportional, it is a prerequisitive of writing scores. Each rhythmic value has been marked with a separate sign for centuries. The distance between the notes does not modify their length and their value, but the proportional distance between the heads makes their reading easier.

József Karai: De profundis (1984)

As per the notation, recitation is not balanced but should be accentuated properly according to the convention of the gregorian performance. The mark ᴗ, which was originally used to mark the metrical foot, refers to the accentuated (and not the short) syllable. The arrangement of the notes, the shorter or longer distance between them refer to the well-accentuated delivery of the text.

The varying distance between the notes indicates the rhythm of the text only approximately.

b. Tempo notation of the group of notes

Accelerating the group of notes

Decelerating the group of notes

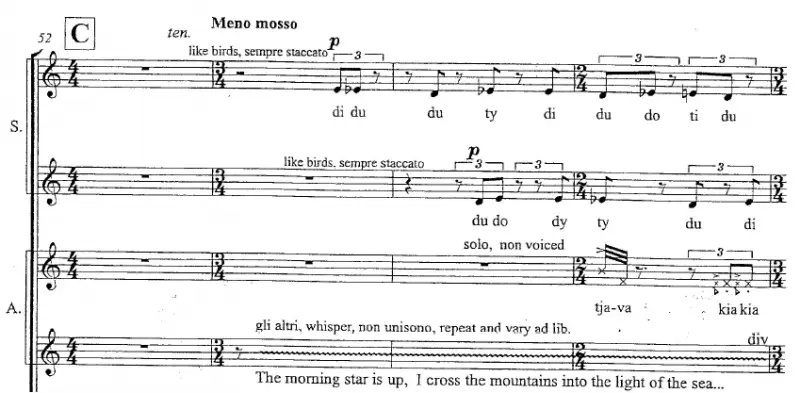

Sándor Szokolay (1931-2013): Tabernacle

The graphic elements illustrate primarily the tempo instructions visually proportionally. The gradually thickening and opening beams mean acceleration, the gradually closing beams mean deceleration. While the conventional accelerando or ritartando refer to longer phases, the graphic solution refers only to individual groups of notes. The performance creates parlando or rubato sensation, rather than continuous tempo change.

Sándor Szokolay: Tabernacle (1980)

In the final movement of the cycle ”Denoument” the groups of 12 notes move and repeat in fixed or free rhythm, faster and faster. The harmonic frame is mostly defined by the points met in the sixth interval.

c. Time axis

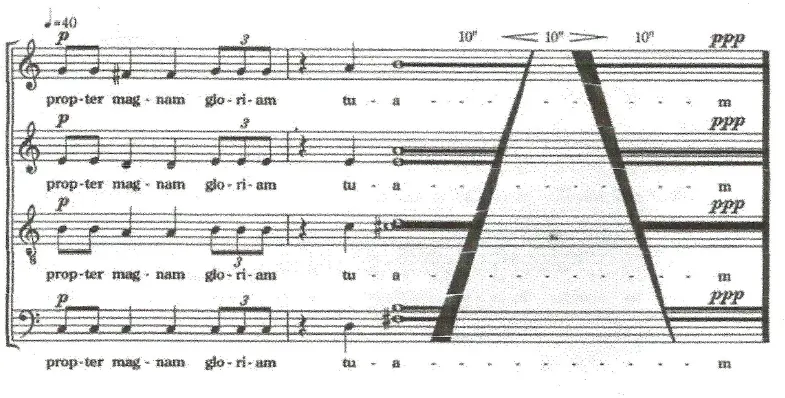

Javier Busto (1949*): Gloria

The use of the time axis can also be interpreted as part of the proportional notation. The musical unit defined in seconds has a major role, so the performance requires an excellent sense of proportion. Counting the seconds has to be avoided, but one needs to be aware of their role in the big form and processes.

According to the musical notation the ten-minute decrescendo in the bass part is followed by a crescendo-decrescendo of the same length, and by a gradual fading away.

Javier Busto: Missa Brevis pro pace / Gloria (1987)

Text Instructions

In the conventional musical notation the composer usually refers to the dynamics, tempo and character of the performance with one word. This happens in Italian technical words that are known by all composers and performers. At the beginning of the twentieth century the French music uses a mixed technical language: Italian and French.

The new instructions can vary from composer to composer, so the explanation of these graphics can be several pages in length and they are attached to the music as a mini glossary. In case it is not enough, the composer gives an exact, sometimes lengthy description at certain points of the music or in the footnote. It can happen in any language, but the most often uses the classical Italian musical technical terms, too.

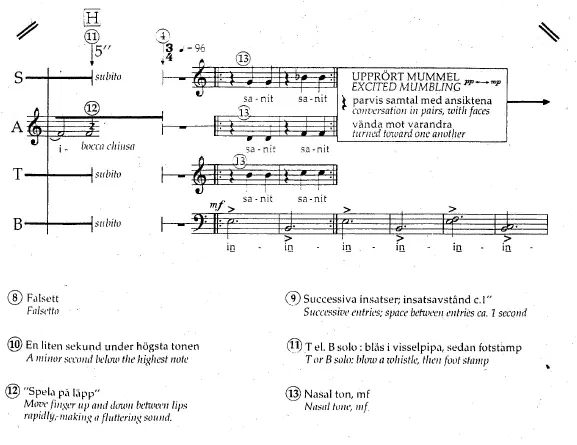

The following extract requires thorough study:

Arne Mellnäs (1933-2002): Bossa Buffa

Arne Mellnäs: Bossa Buffa (1973)

The Graphic Musical Notation

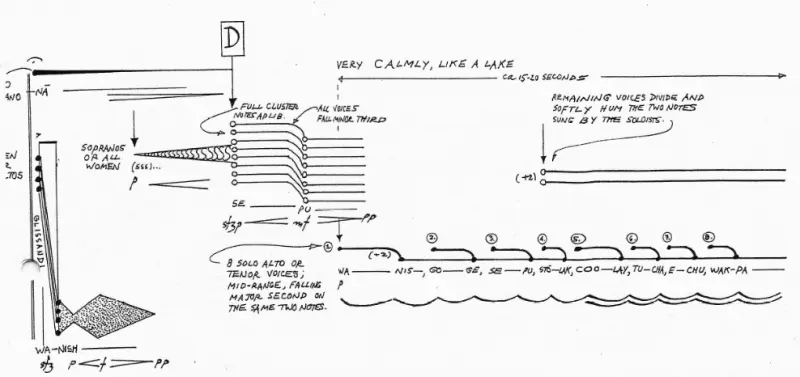

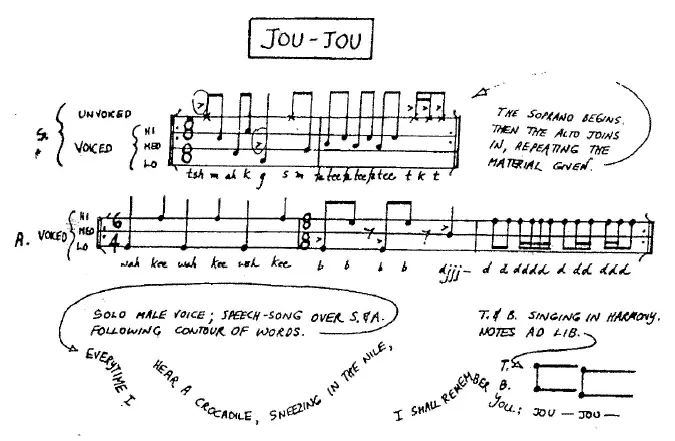

R. Murray Schafer (1933*): Miniwanka

The path the water takes from the clouds to the ocean. The text describes the water’s different state of matter using North-American Indian expressions. There are hardly any specific notes or rhythm in the composition, but there are a lot of instructions by the composer regarding concrete musical processes and sound imitation, either in text or graphic form.

There is no use arguing whether a composition like this is music or vocal timbre, noise or performance. It is a challenge for the conductor to decipher the notation, and it is an exciting adventure for the choir to perform works of similar nature.

R. Murray Schafer: Miniwanka (1971)

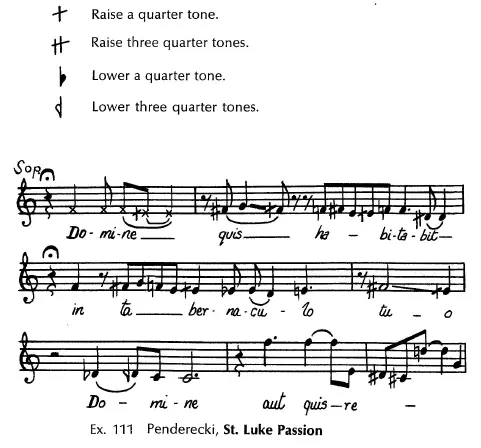

Special marks referring to the intonation

Krzysztof Penderecki: Passio Et Mors Domini Nostri Jesu Christi Secundum Lucam (1966)

The Challenges of the Performance

For the conductor the problem is not understanding the notation but sounding it. Although the composer notes down the interpretation of the graphic signs, but the question is how to make the choir internalize them and apply them to the performance. This is an even more critical question for the although well-prepared, but amateur choirs.

The problem derives from the basic need to belong to a group. The choir is not a group of people who met accidentially, but a community that forms a group to achieve a well-defined, common goal. In case of a choir the common goal is to sound a musical composition. As sounding a choral work is not possible by one person, the experience of singing in a group enables the extension of individual possibilities. At the musical performance the performers take part in a behavioural synchronization that creates emotional bonds among them. By applying the artistic means of expression jointly the performance gives the experience of belonging to the same group of people. A long-lasting collaboration and interaction, the ”sense of us” develops between the group members (Bodnár, 2006). The individual would like to be part of the group at any time, so he or she observes certain rules in the common interest. Breaking the rules can push the individual to the periphery of the group, and he or she might be ruled out.

The classical rule for the choirs is to keep the rule of ”together”: starting and ending the notes at the same time, homogeneous timbre, joint expression etc…Still, the major rule is to give back the information of the notation precisely and jointly. It is not difficult to meet this requirement, as the rhythm, the pitch are given, many times the tempo, the dynamics are also given, and interpreting the text is the basic of expression. In order for the individual to be part of the group, in this case to be a choir member, (s)he needs to observe the rules that (s)he might not go along with. For example, (s)he can not sing louder than the other members, even if (s)he has soloist skills. Despite this, the choir members who bring their character to the fore are more responsive to novelties, even if these novelties are unusual.

The singer, who has got accustomed to the rules of the group and observes them, is now faced with the fact that the performance of certain contemporary choir works requires subverting the conventional rules. These compositions demand individual performance and independence from certain choir members, and many times these requirements are alien for their personalities, so they rather draw back or do not participate in the performance.

A Couple of Suggestions

It is not easy to answer the conductor’s question of what can be done to give a genuine performance. First of all, the choir members need to be convinced that the composition has a genuine message with unique means of expression. These new musical elements, sometimes noises, reinforce the expression, but in certain cases they just create some interesting sounding for a couple of metres and play with the sound. In case of amateur choirs it is important to emphasize that doing unusual things is not ridiculous.

The mentioned motivational techniques will probably not make the reception of these works easier immediately. Recpetion, however, is easier if there are fewer intonational difficulties and the unusual musical elements are brief in the beginning: e.g. stamping at the end of Double, double toil and trouble by Jaakko Mäntyjärvi. The joint and free performance of prosaic, perhaps sprechgesang parts can be prepared by joint poetry recital, the tempo and dynamics of which are directed by the conductor. Up to this pont any choir member can be led to, but it is more difficult to encourage them to initiate or to improvise.

It was the Swdish conductor Gunnar Eriksson who elaborated the methodology of how to perform improvisatory parts joyfully. For instance, the musical material presented by the conductor can be varied freely by each choir member and several, different layers can build a new version. Free variation is possible not only with the melody, but also with the rhythm and the tempo, silence is an option, too etc.. (Eriksson).

Preparing the Reception

In case of adult choirs the hardship of the performance derives from the fact that the choir members themselves do not become recipients, so without genuine interpretation no connection is established between the composer and the audience. The question emerges when it is time to prepare the performer and the audience to receive the ”new” music besides the classical one. The answer for the question of when is simple: when the personality is the most open, that is in the childhood. The answer for the question of how is more complicated.

There are several books thematizing methodologies that have been tested and are applicable in musical classes. The aim always is to gain experience together. Children can play with the vocal timbre, the rhythm, the character etc., but the main goal is the joy of the performance. The present thesis does not aim to present the methodological books of this topic, but a short overview can be useful. The English composer Brian Dennis (1941-1998) had the children do playful exercises for which conventional notation was not necessary, only the children’s creativity. The first step is to compare the sounds and the noises of the environment, then to distinguish definite and indefinite pitch, and to observe and draw musical motion. Later on, based on the clues the teacher offers, they improvise without fear, primarily on percussions. At this point improvisation does not necessarily need to contain musical sound.

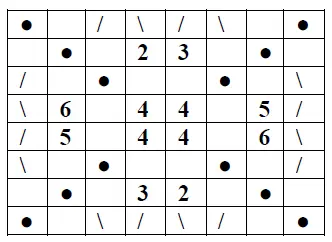

One of Brian Dennis’s magic squares:

Eight separate ”compositions” played on idiophone. The squares indicate the unit of time, which can be a metre or a beat. The empty squares mean breaks, the numbers indicate the number of notes within a unit of time, the tilted lines mark gradually accelerating or decelerating tremolos.

Later on Brain Dennis had the children prepare drawings – graphic notations – depicting musical motion and character. After discussing the drawings they improvised on tuned instruments setting aside tonality and melody (Szabó).

We do not have intonational problems in the early childhood because this problem appears in line with the development of musical literacy skills. Later on, there are many techniques applicable for singing atonal melodies, that is hitting the right note without sense of key. The most well-known skill-building book is the collection Modus Novus by Lars Edlund, which guides the singer gradually to the stable intonation of the twentieth-century music through exercises and musical extracts.

Other Typical Excerpts:

János Vajda (1948*): Via crucis (1983)

Alberto Grau (1937*): Kasar mie la gaji (1990)

Jaakko Mäntyjärvi (1963*): Four Shakespeare Songs/ Double, Double Toil and Trouble (1984)

Lorenzo Donati (1972*): Mignonne (2018)

Ko Matsushita (1962*): Jubilate Deo (2008)

Adrian Pop (1951*): Tre Madrigali / Rifugio d’uccelli notturni (1985)

György Kurtág (1926*): Omaggio a Luigi Nono (1979)

György Orbán (1947*): Motet (1969-1979)

Věroslav Neumann (1931-2006): Nářek opuštěné Ariadny (1970)

Stephen Leek (1959*): Kungala (1998)

Arne Mellnäs (1933-2002): Aglepta (1969)

R. Murray Schafer (1933*): Felix’s girls/6: Jou-Jou (1979)

József Karai (1927-2013): Spring cries (1981)

József Karai (1927-2013): De profundis (1984)

Eric Whitacre (1970*): Cloudburst (1991)

Karin Rehnqvist (1957*): Haya! (2009)

Werner Jacob (1938-2006): …ein Schatten auf Erden (2004)

References

- Anonymus (cca.900): Musica Enchiriadis., Thesaurus Misucarum Latinarum [on-line]

http://markalburgermusichistory.blogspot.com/7820/01/anonymous-b-c-820.html - Bodnár Gabriella (2006): A csoport [The Group]. In: Juhász Márta & Takács Ildikó (eds.): Pszichológia. Typotex Kiadó, Budapest. 179-199.

- Cardine, Eugene (1968): Semiologia Gregoriana. Pontificio Instituto di Musica Sacra, Roma.

- Copland, Aaron (1973): Az új zene 1900-1960 [The New Music, 1900-1960]. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Eriksson, Gunnar (2008): Kör ad lib (Grøn). Bo Ejeby Förlag, Göteborg.

- Gülke, Peter (1979): Szerzetesek, polgárok, trubadúrok. A középkor zenéje [Mönche, Bürger, Minnesänger. Musik in der Gesellschaft des europäischen Mittelalters]. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Graduale Triplex (1979): Abbaye Saint-Pierre de Solesmes & Desclée, Paris-Tournai.

- Haraszti Enikő (2010): A futurista (zaj-) zenefelfogás alapjai [Basics of Futuristic (Noice-) Music Perception]. Helikon Irodalomtudományi Szemle, 2010/3.

- Ignácz Ádám and Kertész Gergely (2010): A gépzene gyökerei: Russolo technikai utópiája [The Roots of Machine-music: Russolo’s Technical Utopia]. 2000, Irodalmi és Társadalmi havi lap, 9. 1.

http://ketezer.hu/2010/01/a-gepzene-gyokerei-russolo-technikai-utopiaja/ - John Cage: Complete Works.

http://johncage.org/pp/John-Cage-Work-Detail.cfm?work_ID=134 - Mabry, Sharon (2002): Exploring Twentieth-Century Vocal Music: A Practical Guide to Innovations in Performance and Repertoire.

https://www.questia.com/read/103557998/exploring-twentieth-century-vocal- music-a-practical - Nyman, Michael (1999): Az experimentális zene. Cage és utókora [Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond]. Hungarian translation: Pintér Tibor. Magyar Műhely Kiadó, 2005.

- Salzman, Eric (1974): A 20. század zenéje [Twentieth Century Music: An Introduction]. Zeneműkiadó Vállalat. Zeneműkiadó Budapest, 1980.

- Szabó Csaba (1977): Hogyan tanítsuk korunk zenéjét [How to Teach the Music of Our Time]. Kritérion Könyvkiadó, Bukarest.

Choral pieces

- Andorka Péter (2017): Véletlen [By Accident]. self-published

- Bengt, Johanssohn: Pater noster. Fazer Music Inc.

- Busto, Javier: O magnum mysterium. Carl Fischer Music.

- Busto, Javier: Missa Brevis Pro pace. Alliance Music.

- Donati, Lorenzo (2018): Mignonne. La Sinfonie d’Orphée, Tours.

- Durkó, Zsolt: Halotti beszéd [Necrology]. Universal Music Publishing Editio Musica Budapest.

- Grau, Alberto (1991): Kasar mie la gaji. Editions a Coeur Joie, Lyon.

- Jacob, Werner (2004): …ein Schatten auf Erden. Edition Gravis, Bad Schwalbach

- Karai József (1984): De profundis. Editio Musica, Budapest.

- Karai József (é.n.) Spring cries. Manuscript.

- Kodály Zoltán (1972): Férfikarok. [Choruses for Male Voices]. Editio Musica, Budapest.

- Kodály Zoltán (1961): Hegyi éjszakák I-IV. [Mountain Nights I-IV.] Editio Musica, Budapest.

- Kocsár Miklós (1989): Six Choruses for Female Choir to Poems by C. Sandburg. Editio Musica, Budapest.

- Kurtág György: Omaggio a Luigi Nono. Universal Music Publishing Editio Musica Budapest.

- Kverno, Trond (1976): Ave maris stella. Walton Music.

- Leek, Stephen (2000): Kungala. Boosy & Hawkes, Inc. U.S.A.

- Liszt, Franz (1922): Der blinde Sänger. Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig

- Mäntyjärvi, Jaakko (1997): Double, Double Toil and Trouble. Sulasol, Helsinki.

- Matsushita, Ko (2010): Jubilate Deo. Carus-Verlag, Stuttgart.

- Mellnäs, Arne (1970): Aglepta. Edition Wilhelm Hansen, Stockholm.

- Mellnäs, Arne (1987): Bossa Buffa. Edition Wilhelm Hansen, Stockholm.

- Neumann, Věroslav (1970): Nářek opuštěné Ariadny. Manuscript.

- Nystedt, Knut: De profundis. Published by G. Schirmer.

- Orbán György (1980): Motetta [Motet]. Editio Musica, Budapest.

- Orbán György (1985): Madrigál [Madrigal]. Universal Music Publishing Editio Musica Budapest.

- Penderecki, Krzysztof: Passio Et Mors Domini Nostri Jesu Christi Secundum Lucam. Schott Music.

- Petrassi, Goffredo (1966): Nonsense. Edizioni Suvini Zerboni, Milano.

- Pop, Adrian: Tre Madrigali/Rifugio d’ucelli notturni.

- Ravel, Maurice (1916): Trois Chansons. Éditions Durand, Paris.

- Szokolay Sándor (1980): Tabernákulum [Tabernacle]. Editio Musica, Budapest.

- Rehnqvist Karin (2009): Haya! Manuscript.

- Schafer, R. Murray (1973): Miniwanka. Universal Edition (Canada) Ltd.

- Schafer, R. Murray (1980): Jou-Jou. Arcana Editions

- Schönberg, Arnold (1914): Pierrot Lunaire. Universal Edition, Vienna.

- Sommereyns, Gwendolyn (2005): Poor Corydon. Euprint BVBA Uitg.

- Vajda János (1987): Via crucis. Editio Musica, Budapest.

- Whitacre, Eric (1996): Cloudburst. Walton Music Corp.