Author: Hedvig Jakab

DOI: 10.5434/9789634902263/10

Abstract

This study focuses on the rich production from the late Renaissance to the Baroque period of early music for keyboard. During the performance of these works, because of the less than reliable sources, a number of problems arise, such as manuscript distribution, and the initial teething problems of printing. Sheet music and its interpretation add another trap for present-day performers for without knowledge of the interpretation practice of that era (articulation, phrasing, agogic, accentuation, ornamentation, fingering, pedalling) coupled with inadequate tools an incorrect style presentation is born. This study provides specific musical examples for the practical implementation of these principles.

Keywords: early music, fingering, pedalling, articulation, ornamentation

Introduction

To better understand the problems with respect to early music interpretation, an overview of how early music performance evolved is useful (Oortmerssen, 2002). Before 1800, mostly contemporary music was played. People mostly composed for their own use. Music from earlier periods was primarily used for didactic purposes. Their own (contemporary) music was addressed with the technique of the time and appropriate knowledge about the style. In the 19th century, however, it became increasingly fashionable to get back to earlier composed music. Philosophical initiatives sparked an interest in the past, whereby many renowned musicians such as Mendelssohn or Brahms became enthusiasts of early music. The focus of attention was relocated to the past, resulting in performances and publications which also included the taste and fashion of the performers’ time. This attitude is evidenced by the fact that an 18th-century collection of organ pieces received several suggestions in relation to fingering, pedalling, phrasing, and registration in the 19th century. By the 20th century, the demand for an approach based on the performance practice indicated in the sources from the period had been articulated, replacing the reliance on current techniques. According to Dolmetsch (1915, p.364): “Before the advent of pianoforte technique, phrasing and fingering on keyboard instruments were indissolubly connected. […] With the ordinary modern system of pianoforte fingering the proper phrasing of the old music is always difficult – frequently impossible.” Improving authentic instrumental technique (which corresponds to the given musical period) is an investment with a return which becomes apparent over time: a refined and reliable technique enriches the spectrum of the player’s musical expression.

Playing Technique, Touch

In early music, keyboard instruments were played by avoiding unnecessary movements. The 16th century low (below-keyboard) position of the elbow began to rise gradually, through the horizontal position in the Baroque era to an even higher position in the 18th century (possibly when the “thumb under” technique became widespread). The arm, however, remained close to the body throughout. The hand position was defined by a line, to which the fingers were aligned in a slightly bent or arced fashion.

Initially, the instrument was played by the fingers only, which were later joined by the wrist (in the late 18th century for staccato play) and the arm (for fortissimo play). The arm weight method as we know it was not known. The key was struck from the finger stem, whereby the fingers did not rise above the keyboard besides staccato.

What techniques were used to touch the keys on different keyboard instruments? A careful but firm technique was used on the clavichord, which was even able to produce a sort of finger vibrato effect through the repeated pressing of a key. The movement of dropping the finger on the harpsichord keyboard was accompanied by support towards the depth of the key with a concentrated striking motion. To ensure the sounding of the pipes, the organ was also played with some sort of a pressing technique. The fortepiano could be sounded with a mixture of the techniques employed on the clavichord and harpsichord. In J. S. Bach’s environment, it was reported to be customary to pull back the fingers after the strike, which was possibly aimed to assist non-legato play and was presumably quite common. In Oortmerssen’s book titled Organ Technique (1998, p.3), he writes the following description: “By keeping the hand as still as possible and maintaining a perfect contact between finger and key, it is possible to realise to the utmost the three phases of the touch: attack – sustain – release. The hand is moved chiefly at the moments when the musical figures succeed one other (‘position-playing’). Where the figures are identical, the same fingering is used as far as possible.” In the most important source for keyboard performance from the period, namely the book titled Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1753, 12.), the following is stated: “If he understands true fingering and has not acquired the habit of making unnecessary gestures, he will play the most difficult things in such a manner that the motion of his hands will be barely noticeable; in particular, one will hear that it is easy for him too.”

Articulation

Articulation refers to the separation of tones from each other and to the methods thereof. All notes have two components: the sounding part and the subsequent articulation silence (which is not opposed to the requirements of “cantabile” instrumental play whatsoever). The forms of articulation range on a broad spectrum from entirely separated notes to continually connected notes: besides staccato, non-legato (“ordentliches fortgehen” or “movimento ordinario”), portato, legato, one may encounter definitions for articulation which are specific to the instrument, melody, rhythm, metre, tempo signature, and emotion.

Staccato, which originated in instrumental music, provides emotional content to sounds. When it is executed, the duration of the note is shortened by half or more, with varying intensity. It is notated by a dot, stroke, or wedge, which, besides denoting separation, may refer to the emotional content and might also relate to dynamics. The stroke and wedge require strong separation (usually) with forte dynamics, while the dot denotes moderate separation (usually) with piano dynamics. This became standard after 1750.

The default articulation in early music for keyboard instruments was non-legato (i.e., ordinary movement, “ordentliches fortgehen” or “movimento ordinario”). The term “ordentliches fortgehen”, which can be translated as “ordinary movement” or “adequate advancement”, was used by Marpurg and reveals by itself the default articulation nature of the concept. “Opposed to legato as well as to staccato is the ordinary movement which consists in lifting the finger from the last key shortly before touching the next one” (Marpurg, 1755, sect. 1). According to Marpurg, tiny spaces separate the similarly notated notes in the execution of “ordentliches fortgehen”. Within the “ordinario” articulation, neither in intensity nor in content can similarly notated notes be played the same way. The description of this articulation can be found in various keyboard publications, from Spain through Italy to German ones from Bach’s time.

The notated duration of a note is never equivalent to the sounded duration. Consequently, every note has two components (Oortmerssen, 1998):

- the sounded part – “tenue” (French for duration, held)

- the silent part – “silence d’articulation” (silence of articulation).

The proportion of the two is not constant and depends on the accent structure of the time signature and on the character of the piece.

An accented note has shorter “silence of articulation” than an unaccented one.

⌐tenue silence d’articulation¬

———————————— - - - -

⌐the value of the note ¬

accented note: ———————————— - - - -

unaccented note: —————— - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Portato requires a different technique on each instrument. In the 18th century, the slur above dots was played on string instruments as separate notes with one bow, on wind instruments as notes with one breath but separated using the diaphragm, and on keyboard instruments with the combination of a firm stroke and legato-like articulation. (In German clavichord performance, this was called “getragenes Spiel”). Importantly, this notation stood for the mildest staccato in fortepiano performance.

Legato (tied play) originated from vocal music as the combination of two-to-four-note neumes, that is, ligatures. It was first used in instrumental music in the 16th century and specifically for keyboard instruments in the early 17th century, when scores first featured the slur. Legato can be defined as the continuous connection between notes with gentle key-touch. The last of the notes under the slur should be shortened to include a small silence of articulation before the accented first member of the next slur. Based on the acoustic environment, more resonant spaces require a longer silence of articulation.

Instrument-specific articulation: keyboard instruments with strings require different articulation from the organ, which is due to the distinct build, way of sounding, and literature of these instruments. For example, the improvisation style on the organ which is dominated by dissonances of syncopated preparation and regular dissolution requires more connected articulation. The special acoustic and technical characteristics of the clavichord favour legato play, while the articulation spectrum of the harpsichord is broader. The dominance of legato as default articulation started with the appearance of a new instrument, namely the fortepiano, in the early 18th century. By the late 18th century, legato had also become the default articulation for the organ, mostly because of the popularity of the chorale.

Melodic line articulation: a scale-like melodic line requires more connected articulation, while the distance between notes may be larger with interval jumps. Descending melodies should be played rather legato, for dynamic reasons: descending creates a diminuendo effect, whereas ascending resembles crescendo. Chromatic sequences should be articulated in a more connected way than diatonic ones because of their emotional content and the fact that they cannot be denser melodically (Lohmann, 1987).

Rhythm articulation: the most extensive rhythm of a piece should be played with default articulation, which should be selected based on the character of the piece. Faster rhythms should be performed rather separately and longer rhythms are to be played in a more connected way.

Metre articulation: the gravity of the performance is proportional to the rhythmic values which constitute the metre. For example, 3/8 should be more heavily than 3/4. Similarly, 2/4 has a more massive character than 2/2 (alla breve).

Tempo signature articulation: composers’ instructions of Allegro, Presto, and Vivace require a light, mostly staccato (non-legato) articulation. Adagio, Largo, and similar movements should mostly be played legato. “In general, the liveliness of allegros is conveyed by detached notes, and the expressiveness of adagios by sustained, slurred notes […] even when not so marked” (Bach C. P. E., 1753, 5).

Emotional articulation: the performance and style of early music is emotionally rich with a broad spectrum for expressing emotions. Selecting the adequate articulation for the character of the piece contributes greatly to the emotional coherence of Baroque music. Accordingly, legato expresses a sad character and staccato represents a happy character the best.

Genre-specific articulation: the movements of French organ music carry the following articulations: Grand plein jeu, grave articulation; the related Petit plein jeu, lighter articulation; Duo and Basse de Trompette, pronounced performance; all Récit movements, light and fine articulation; fugues, grave performance; dance movements, primarily light articulation. Generally, French compositions are lighter, Italian ones are moderate, while German works require a grave performance style.

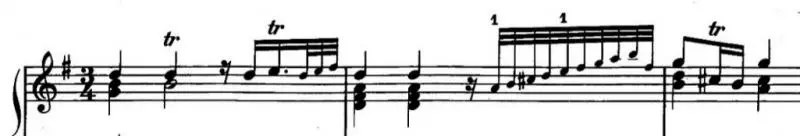

Dotted rhythms, Lombard rhythm: in the French tradition, both members of dotted rhythms should be articulated separately, while in the Italian tradition, the dotted note is tied to the next short note. In Germany, both solutions were in use: the former in Allegros and Ouvertures (French overture style) (Excerpt 1) and the latter in Adagio movements. Both notes of the Lombard rhythm[1] should be played legato, but a rather significant degree of separation is necessary between note pairs (Excerpt 2).

Excerpt 1: French overture style (Bach: Partita in B minor BWV 831)

Excerpt 2: Lombard rhythm (Buxtehude: Prelude in E minor BuxWV 142)

Ornament articulation: ornaments should be played legato in most cases. The appoggiatura should be connected to the principal note. The notated delay requires legato articulation, if possible.

Articulation and early fingering systems: the use of early fingering system is related to both articulation and accentuation. The good and bad (accented and unaccented) note pairs of “ordentliches fortgehen” have a short silence of articulation between them, which should be eliminated by keyboard instrument performers through continuous and equal performance. A longer silence of articulation is only possible for major jumps and finger substitution when two subsequent “good” notes are played (Excerpt 3). The latter refers to monophonic play, but it was sometimes also used in one-handed polyphony (Excerpt 4), as silent finger substitution did not exist yet.

Excerpt 3: The relocation of the “good” finger in monophonic play (17th century, Netherlands)

Excerpt 4: Finger relocation in polyphonic play (left hand)

Phrasing

The two most important principles of early music performance are understandability and expressivity. The former is especially important because the acoustic outline of a certain note held a greater significance up to the 18th century than later. Phrasing is responsible for the clarity of musical connections for listeners. Its theory dates back to around 1700, but phrasing instructions such as the fermata (marked by a dot [·]) or the slur were used as early as the 17th century. In analogy to the formal and grammatical structure of oration, 18th century compositions consisted of paragraphs, sentences, and phrases, the combination of which is always accented. In practice, phrasing is conducted by striking the first, accented note of the initial phrase strongly and prolonging it using devices of agogics. If a new phrase needs to be initiated within a musical process, the last note of the previous phrase should be shortened to provide acoustic separation for the new phrase. There are two ways to do this: either some time needs to be taken out of the note before (to achieve an appreciable silence) or additional time should be inserted before the new phrase (not shortening the previous note), thus delaying it. The first solution achieves less separation, which is why the second one should be applied between larger sections. The use of inserted (“stolen”) time also raises questions of agogics (Donington, 1978). This is described by Frescobaldi (1615-16, 3) and Quantz (1752, 4) in the following way: “[…] a pause prevents confusion between one phrase and another.” “The end of what goes before, and the start of what follows, should be well separated and distinguished one from the other.” A perfect execution is warranted by the adherence to the principle of in-line shaping.

Agogics

Agogics is crucial for organ performance. Handling time in the proper way is especially important for recognising the emotional content of the musical occurrence. Besides the separation of phrases (phrasing), there are other possible measures, some of which belong to the field of agogics (Donington, 1978). The initial notes of a phrase can be prolonged as it is customary in oration. The desired tempo is reached gradually, which emphasises the resemblance to speech. Between sections, the tempo can be stretched, not amounting to a ritardando or rallentando, however. At the introduction of the next phrase, a slight delay may be used if it is justified musically. “[Certain] notes as well as rests must sometimes as a result of the expression be allowed a longer value than the notation shows” (Bach C. P. E., 1753, 28).

Accent

Proper accentuation makes the metric order of music perceivable and enables understandability and expressivity. There are three types of musical accents: grammatical, oratorical (pathetic), and logical (Lohmann, 1987).

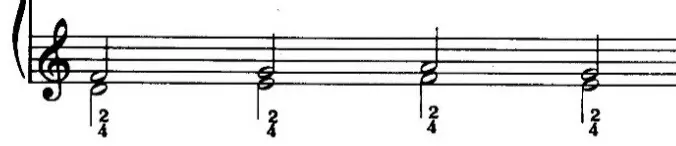

Based on the principle of contrast between arsis and thesis, grammatical accent highlights the accent structure within a bar, namely that similarly notated notes do not have similar significance. The principle of arsis and thesis was based on the approach of “quantitas intrinseca notarum” or “internal content of notes” in the 18th century. According to this, notes of a given duration (with the same “quantitas extrinseca” or “external content”) should be ordered by their internal content: they can be either “good” (that is, “internally long”) or “bad” (that is, “internally short”). This can be executed in performance through the following tools: rhythmic inequality (limited to certain styles and note values), dynamic differentiation, articulation (the most important tool for keyboard players between the 16th and 18th centuries), and the prolonging of important notes in the voice, resembling tempo rubato. The theory of the accent structure of a bar evolved from the approach of “quantitas intrinseca notarum”, resulting in the hierarchic ordering of different accents. Within primary and secondary accents, rhythmic values can be divided into “good” and “bad” (accented and unaccented) notes, which are performed with different articulation. (Using early fingering systems results in the desired articulation almost automatically.) In the 2/4 metre, the first beat is accented and the second is not; more specifically the two eighth notes within the first crotchet are accented-unaccented, while the second pair of eighth notes are also accented-unaccented but in a subtler way. If, however, sixteenth notes appear in the bar, both the sixteenth quadruple under the (primary) accent and the one under the unaccented second beat are played “good-bad-good-bad” (accented-unaccented-accented-unaccented), which is best performed using an early fingering system and proper articulation. It is important to mention that third element of the quadruples, which is “good” (accented), can be defined more precisely as “less good” (or less accented). Similarly, the fourth element, which is “bad” (unaccented), is not equivalent to the second. It is clear that there is a hierarchy both between and within beats.

Regular bar accents:

1. Duple metres have one accent on the first beat:

1.accented — 2.unaccented

2. Quadruple metres have two accents, the primary on the first beat and the secondary on the third:

1.accented — 2.unaccented — 3.(less) accented — 4.unaccented

3. In triple metres, there is one primary accent, which might be accompanied by a secondary accent on third (sometimes second) beat:

1.accented — 2.unaccented — 3.(less) accented (excerpt 5) OR

1.accented — 2.(less) accented — 3.unaccented (excerpt 14)

4. For triplet-based meters (6/8, 9/8, etc.) there are two possibilities:

4.1. the first members of a triple-groups get the accent (and possibly the third members get a secondary accent):

6/8:

1.accented — 2.unaccented — 3.unaccented (possibly less accented) — 4.accented — 5.unaccented — 6.unaccented (possibly less accented)

9/8:

1.accented — 2.unaccented — 3.unaccented (possibly less accented) — 4.accented — 5.unaccented — 6.unaccented (possibly less accented) — 7.accented — 8.unaccented — 9.unaccented (possibly less accented)

4.2. triplet-based metres follow an analogous accent structure to other metres:

6/8 has one accent in analogy to 2/4:

1.accented — 2.unaccented — 3.unaccented — 4.unaccented — 5.unaccented — 6.unaccented

9/8 has two possibilities in analogy to 3/4 (accent on beats 1-2 or 1-3):

1.accented — 2.unaccented — 3.unaccented — 4.(less) accented — 5.unaccented — 6.unaccented — 7.unaccented — 8.unaccented — 9.unaccented OR:

1.accented — 2.unaccented — 3.unaccented — 4.unaccented — 5.unaccented — 6.unaccented — 7.(less) accented — 8.unaccented — 9.unaccented

12/8 has two accents in analogy to 4/4:

1.accented — 2.unaccented — 3.unaccented — 4.unaccented — 5.unaccented — 6.unaccented — 7.(less) accented — 8.unaccented — 9.unaccented — 10.unaccented — 11.unaccented — 12.unaccented

Excerpt 5: Triple metre with accented first and third beats

Oratorical (pathetic) accent, which is intended to highlight unusually expressive notes, does not necessarily coincide with the grammatical accent. It is common for syncopated notes and for musical moments which are dissonant in the dominant harmonic arrangement. Furthermore, it is used for unusually long, high, or low notes.

Logical accent assists the understanding of the cohesion between musical phrases. If the composer (and not the publisher) prescribes a slur, the first of the notes under it should be more accented than the rest, which is related to the phrasing-articulation-accent problem. Accent instructions may also take the form of a dot, stroke, or wedge if the accent function of the notation is clear from the musical context.

Primary accents should be further emphasised with agogic stretching, while secondary accents can be marked by a longer-than-usual silence of articulation in “ordentliches fortgehen”.

Fingering

“At the keyboard almost anything can be expressed even with the wrong fingering, although with prodigious difficulty and awkwardness” (C. P. E. Bach, 1753, 3). Remarks such as these by C. P. E. Bach show the importance of proper fingering in the 18th century. Historical fingering and pedalling served not just technical but also (more importantly) musical purposes.

From the 16th century, books about keyboard instruments attempted to present contemporary fingering and pedalling systematically. Yet every fingering description is ambiguous to some extent because there are exceptions to the rules. The existing information about fingering helps us understand the technical solutions of the repertoire from various periods and regions. By attempting and learning earlier fingering systems, present-day keyboard instrument players can understand the intimate interaction between fingering (pedalling) and musical expression.

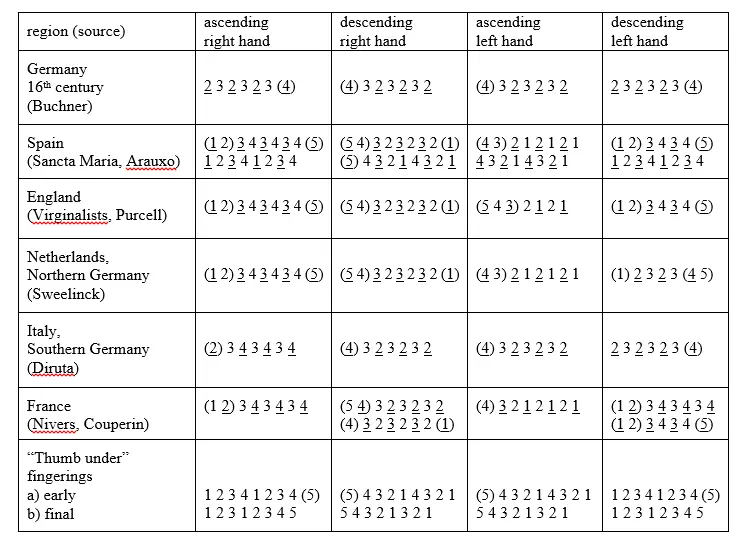

The diversity of fingering systems is evident from the first instruction materials about keyboard instruments. The key theoretical concept relies on the unequal length and strength of fingers. However, different European regions regarded different fingers stronger or weaker, but there was consensus on avoiding the thumb and little finger if possible (Fytika, 2004). “Good” (accented) notes were played by “good” fingers, while “bad” (unaccented) notes were struck by “bad” fingers. The distinction into “good” and “bad” fingers across regional systems is presented in Table 1. The numbers in parentheses represent the initial and closing fingering options. The scale could have started and ended (or taken a turn) with position fingering, that is, with the inclusion of the thumb and little finger, but there was also a possibility to perform a scale sequence by only two fingers.

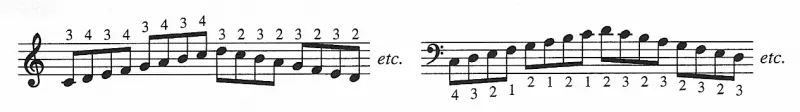

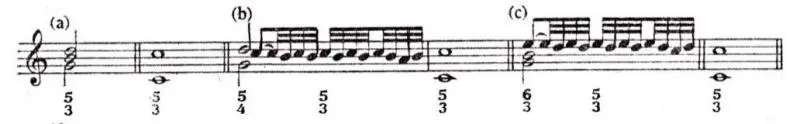

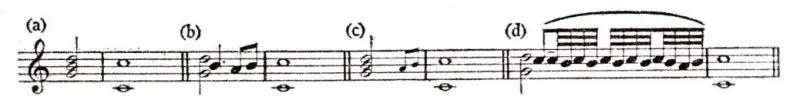

The figuration of early music had two fingering systems (Jakab, 2007):

- Pair fingering, whereby adjacent fingers form pairs, especially in partial or full scale sequences.

- Crossing fingering, whereby the accented note is played with the shorter second and fourth finger, while the longer middle finger crosses over it.

- Position fingering, whereby fingers follow each other in their natural order (Excerpt 6).

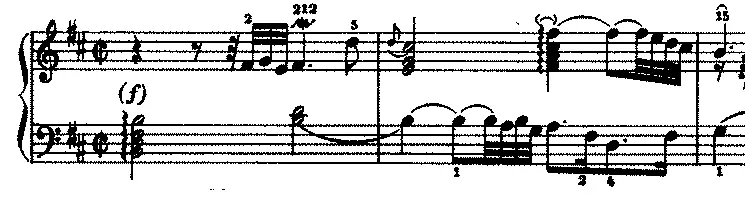

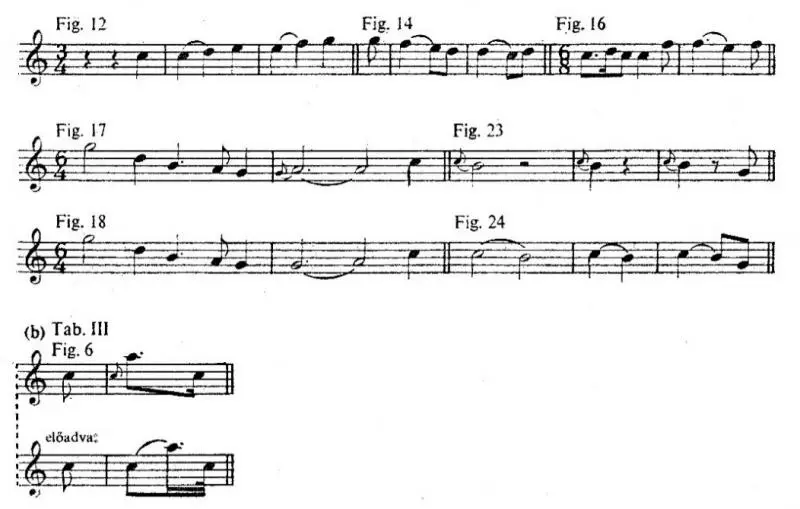

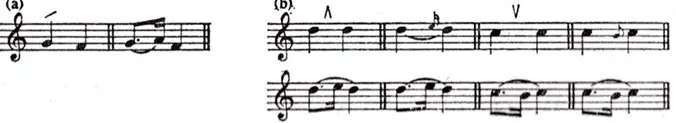

Excerpt 6: Pair, crossing, and position fingering[2]

Until the 18th century, scales were played by two fingers, the longer over the shorter (Table 1). In the Netherlands, pair fingering was in use (Excerpt 7), whereby the “good” fingers were not the same on both hands: the “good” finger was the third on the right and the second (and fourth) on the left.

Excerpt 7: Netherlands, pair fingering by Sweelinck

In Italy, Diruta (1593/1609) employed crossing fingering, whereby the third finger was always “bad”, which distinguished it from other systems (Table 1). Importantly, the execution of this system should not lead to a shifted pair or a tied result (which is “not to one’s liking”) but rather to a sparkling, elegant, and finely structured sound. The hand should be turned in the direction of the scale (upwards or downwards), which contributes greatly to the consistency of articulation. This technique was also common in Southern Germany, popularised by the renowned teacher Christian Erbach from Augsburg. In crossing fingering, the second and fourth fingers are “good” for both hands (although the descending scales of the left hand evolves into pair fingering) (Excerpt 8).

Excerpt 8: Italy, crossing fingering by Diruta

Table 1: The underlined numbers denote the “good” fingers, the numbers in parentheses represent the initial and closing notes of the scale (Lohmann, 1987. 35)

A markedly different fingering concept was developed by English Virginalists, for whom the principal finger was the third for both hands, just as with Sweelinck’s school (Table 1). Musicians from both regions were able to play as many embellishments over the accented notes of figurations as needed (by the third finger). In left hand sequences, Virginalists put emphasis on the thumb (Excerpt 9) (Lindley and Boxall, 1992).

Excerpt 9: Fingering proposed by English Virginalists (Orlando Gibbons, Prelude)

The question arises as to whether it is possible to achieve the same sound with modern fingering as with early fingering systems; in other words, whether a scale can be played with current fingering to create the illusion of “good” and “bad” notes. The question reflects complete ignorance about the performance technique of the period. Its complexity is described in C. P. E. Bach’s Versuch (1753, 4): “Correct employment of the fingers is inseparably related to the whole art of performance. More is lost through poor fingering than can be replaced by all conceivable artistry and good taste.” Other 19th-century sources suggest the same. The quote clearly shows that the correct fingering guarantees a refined technique as well as an expressive performance. It is important to highlight that period-specific fingering systems might provide an answer to other practical questions (such as tempo, accent, phrasing, and articulation).

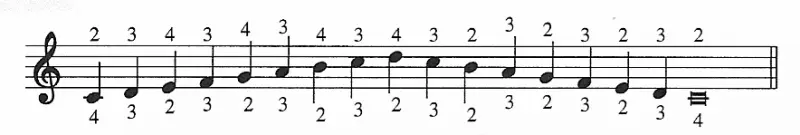

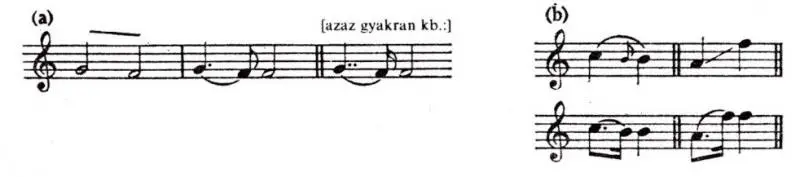

In early music, each interval had a set fingering, which was also used for one-handed polyphony. Interval fingerings usually avoided the first and fifth fingers. Scale sequences of the same interval (interval sequences) were played by the same fingers. For example, parallel thirds were performed by the second and fourth fingers (Excerpt 10) and parallel sixths were played by the first and fifth fingers. It was Couperin’s idea to stop using constant fingerings to achieve smoother articulation. However, quick thirds were only played by fingers 2 and 4.

Excerpt 10: Two fingerings for the parallel thirds (finger replacement and changing fingering)

Excerpt 11: Different interval fingerings and the fingering of one-handed polyphony (Ammerbach)

Excerpt 12: Long notes are played by the same fingers

In the investigated period, playing of two consecutive notes with one finger was not allowed, but there were some exceptions, for example long notes one after the other (half or whole notes) were usually played by the same fingers (Excerpt 12). Other examples include scale sequences with two good notes following each other (e.g., in transitioning from slower to quicker movements) (Excerpt 3) and one-handed polyphonic play (due to the set interval fingering) (Excerpts 4 and 11).

The new system of tuning allowed the use of more sharps and flats on keyboard instruments, which brought about the more frequent use of the thumb (especially in scales) (Oortmerssen, 2002). The “thumb under” technique was introduced in Germany, France, and England around the same time, at the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, mostly because of the influence of Bach, Rameau, and Italian musicians.

“My deceased father [i.e., J. S. Bach] told me that in his youth he used to hear great men who employed their thumbs only when large stretches made it necessary. Because he lived at a time when a gradual but striking change in musical taste was taking place, he was obliged to devise a far more comprehensive fingering and especially to enlarge the role of the thumbs and use them as nature intended: for, among their other good services, they must be employed chiefly in the difficult tonalities. Hereby, they rose from their former uselessness to the rank of principal finger” (Bach C. P. E., 1753. 7).

In early music (especially in scale passages), the thumb was not allowed to touch black keys, except for one-handed polyphonic play. Since scales with black keys were not common in the period, this occurred quite infrequently (Excerpt 11). The fifth finger was allowed to strike black keys in duophonic performance (interval play) but usually not in monophonic play (Excerpt 11). In the 18th century, it was still customary to play scales according to 17th-century fingering (that is, in pairs), but the new scales which resulted from developments in tuning required the use of the thumb increasingly (since the old system of pair fingering was more difficult to execute with more black keys). Consequently, the “thumb under” technique was used for the ascending right and descending left after fingers 2, 3, and 4; in the opposite direction, fingers 2, 3, and 4 were above the thumb. It is important to note that finger 5 could follow the thumb neither below nor above. It was also not allowed to place finger 2 above finger 3 and finger 4 above finger 5 (although these could seem as the only viable solutions in problematic situations).

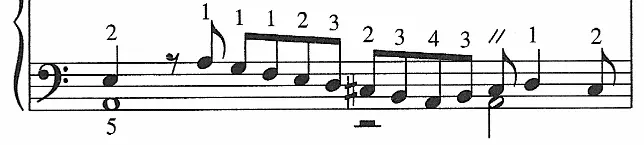

Excerpt 13: Step figuration with repeated fingering for the right and left hands

Repeated step figurations (Excerpt 13) were played with the same fingering, with potential deviations when black keys were present in the figuration. The ascending step motif for the right hand was played with 3232 fingering, the descending version alternated between 3434 and 2323. For the left hand, ascending followed 3434 or 2323 and descending 3232. For very quick passages, the 12341234 fingering for the right hand was another option (Excerpt 14).

Excerpt 14: Quick passage for four fingers (Händel: Ciacona)

For repetition, alternating fingers were used (Excerpt 15), but a four-finger solution also existed: 4321 (left hand), 1234 (right hand).

Excerpt 15: Repetition with alternating fingers

The sigh-motif (suspiratio) was to be played by the same finger pair (3-4 right ascending and left descending; 3-2 right descending and left ascending).

If voices crossed each other, the crossing of hands was advised by Marpurg (1765, 7) (Excerpt 16).

Excerpt 16: Voice crossing

On a unison note, the key had to be played with both hands (Excerpt 16). In four-part continuous play, it was advised to designate 2 voices to each hand (Excerpt 11) (Oortmerssen, 2002). Marpurg suggests that the same finger should be advanced in playing the syncopatedly delayed parallel thirds of two voices for one hand (Excerpt 17).

Excerpt 17: Fingering for syncopatedly delayed parallel thirds for one hand

Unison passages were preferably played with both hands, divided into two sections based on stems and beams (and on the progression of motifs) (Excerpt 18).

Excerpt 18: Unison passages played with both hands

Ornaments were played by fingers 3-2 for the right and fingers 1-2 for the left hand, with the possibility of fingering 3-4 on the right and 2-3 on the left in special cases. Silent finger substitution was first used by Couperin in the early 18th century and became frequent in organ performance due to the popularity of chorales from the late 18th century. It could only be employed in the performance of solo repertoire in exceptional cases. C. P. E. Bach (1753, 7) was not convinced by the technique, which he thought Couperin used “too frequently and without need”.

Let us conclude with an anecdote by Johann Mattheson about Jacob Praetorius, organ master from Hamburg, which reveals the importance of learning the proper fingering for musicians at the time.

“As he heard of an exceptional organist in Amsterdam, he decided to travel there and take lessons. The leaders of Jacob Kirche also encouraged him and promised to cover half of his costs. So he went to study under Joh. Pet. Swelink, or Schweling, who taught him a truly original fingering technique, which was quite unusual but very good” (Mattheson, 1740).

The evolution of new fingering systems and the size and shape of keys occurred simultaneously. The most apparent change was in the length of white keys. In the 16th and 17th centuries, they were relatively short to accommodate the fingertip only. White keys were struck at the imaginary line at the stem of black keys to enable access to black keys with a small movement if necessary. As the technique of crossing over and under spread, the length of white keys grew, resulting in more space for the hands. By the 19th century, keys had reached their final length, which is why techniques of the period (including silent finger substitution and the “thumb under” technique) can be played even today without difficulty.

Pedalling

The pedals of historical organs were relatively short, leaving a small area of contact between foot and key, which is why crossing feet must have been difficult (Oortmerssen, 2002). 18th-century pedalling guidelines suggest that the most common solution was the use of alternating feet but do not answer the question about the execution of “crossing feet”. Most likely, the solution was analogous to early fingering systems in that continuous pedalling was achieved through quick position changes. In the 17th century, organ pedals were not parallel to the ground: pedal keys were higher in the front and descended through the back. The use of the heel was too difficult or even impossible. There was not enough space because of the short keys, and the area where the heel could have been used was positioned too deep[3]. Until the mid-18th century, pedalling was restricted to the toe. It wasn’t until the 19th century that the heel played such a big role in the pedal-play as the toe. In conclusion, the tip of the foot (toe), in analogy to the tip of the finger (fingertip), is the most adequate to precisely execute touch. Long notes of the 16th and 17th centuries (e.g., notes of Cantus firmus) were played by one foot; on the right side of pedals by the right foot, on the left side by the left. When the pedal voice evolved into a bass line (e.g., in pieces by Scheidemann and Van Noordt), alternating feet were used: upwards L R L R L R and downwards R L R L R L[4].

Ornamentation

In the performance practice of early music, ornamentation and improvisation evolved together. Due to inconsistencies in notation, there are numerous small ornaments, which are difficult to categorise. If the sign for an ornament is absent, performers should not be discouraged from employing the ornament which suits the musical context. Conversely, if an ornament is present, it should not be taken as an obligation to perform that specific ornament. In French Baroque organ music, however, embellishments were notated rigorously, which leaves performers with less liberty (which still exists, according to the Baroque approach).

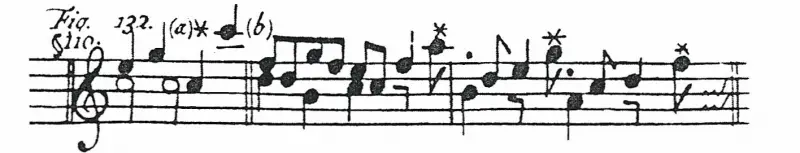

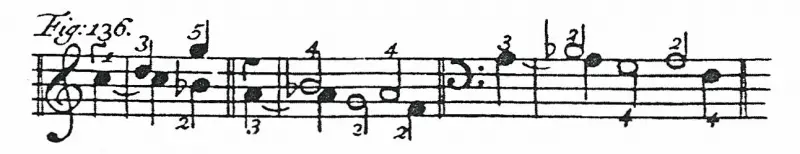

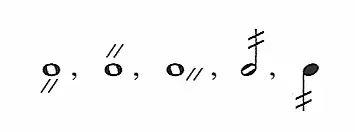

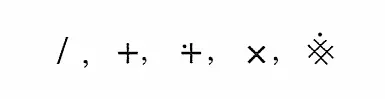

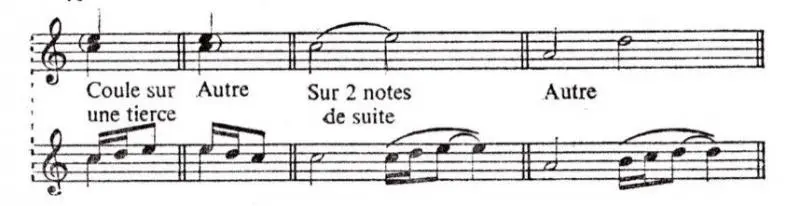

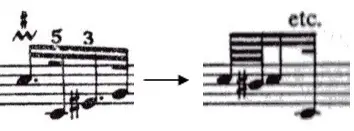

At the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries in the Netherlands, the most common notation for ornaments was the double stroke (Jakab, 2007), which could be placed above, next to, or below a whole note, or written as crossing the note stem diagonally[5].

Figure 1: Ornament notation with double stroke

Other notations were also used[6].

Figure 2: Other notations

The execution of ornaments can be deduced from explanations of various sources. Frederick Neumann’s study on Baroque ornamentation (1983) considers 17th-century publications. Other sources include the fingerings denoted on embellished notes, which have not been studied extensively, however. In conclusion, notations indicate that some embellishment is required, while the execution can be derived from the musical context.

In early music performance, the accent structure of the bar is significant (see chapter 6), which is also true for the execution of embellishments. If the ornament falls between strong beats, it behaves as a passing or changing note, possibly including a note of anticipation, which should be slipped in lightly as late as possible before the following beat. By contrast, accented ornaments fall on the strong beat, behave as accented passing or changing notes, and are not anticipatory. Turns (Doppelschlag) and slides (Schleifer) may be either accented or unaccented, but trills and appoggiaturas regularly occur accented. Baroque ornaments on the beat are usually accented, that is, the time to execute one is taken away from the note it is attached to and not the preceding note (which is a common mistake among performers). C. P. E. Bach writes in his Versuch (1753, 23): “[…] while the previous note is never curtailed, the following note loses as much of its duration as the [ornamental] notes take away from it.” To this he adds in the 1787 edition: “It might be thought unnecessary to repeat that the remaining parts including the bass must be sounded with the first note of the ornament. But as often as this rule is invoked, so often is it broken” (Donington, 1978, p.176).

Most ornaments can be played diatonically (according to the prevailing tonality) or chromatically (independently of that). Rhythmic ornaments (such as mordents), which fall on the beat, do not influence the harmony. However, harmonic ornaments (such as long appoggiaturas) do influence the harmony (sometimes to a great extent). The final note should be embellished if it enhances the sense of closure. The following ornaments can be used: long appoggiatura, half-trill without a suffix, long trill with or without termination, short or long mordent, lower appoggiatura with mordent or upper appoggiatura with trill. During interpretation, the function of ornamentation must be specified: melodic, rhythmic, harmonic, or tonal character (e.g., constant trill on the harpsichord to achieve durable resonance). All statements of the fugue theme should be embellished consistently, disregarding the potentially different notation in the score. This is also true for imitations and returns, although not as strictly as with the fugue theme (see, for example, freer imitations).

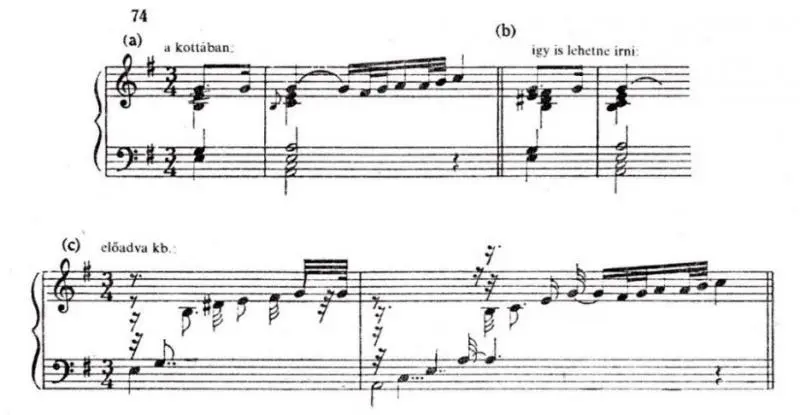

The appoggiatura (from the Italian appoggiare, to lean) is a stressed auxiliary note, which is usually dissonant to the harmony onto which it resolves (Donington, 1978). Thus the dissonant appoggiatura is in essence identical with a suspension. The appoggiatura (leaning note) takes the beat, leaning upon the remainder of the harmony. “Strike [appoggiaturas] with the harmony, that is to say in the time which would [otherwise] be given to the ensuing [mane] note” (Couperin, 1716/1717. 22). “You lean on the appoggiatura to arrive at the main Note intended” (Tosi, 1723. 32).

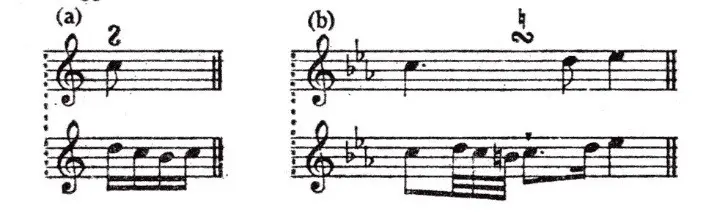

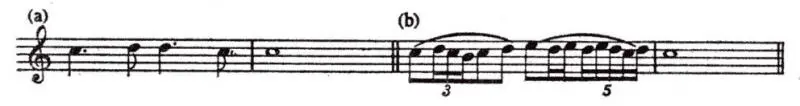

The length of the appoggiatura was moderate in the early Baroque, ranging from one quarter of a note (in duple-metre) to one third of a note (in triple-metre), with negligible harmonic significance. From the last quarter of the 17th century, appoggiaturas began to lengthen, especially as one half of a note (in duple-metre), resulting in an increased harmonic significance. In the 18th century, appoggiaturas were even longer; the later the piece is dated, the longer the appoggiatura. The length of appoggiaturas is also influenced by the musical context, according to the following rules: “Hold the appoggiatura half the length of the main note. [But] if the appoggiatura has to ornament a dotted note, that note is divided into three parts, of which the appoggiatura takes two, and the main note one only: that is to say, the length of the dot. When in six-four or six-eight time [in fact any compound triple time] two notes are found tied together, and the first is dotted, the appoggiatura should be held for the length of the first note including its dot. When there is an appoggiatura before a note, and after [that note] a rest, the appoggiatura is given the length of the note, and the note is the length of the rest” (Quantz, 1752, 7-11). “There are cases in which [the appoggiatura] must be prolonged beyond its normal length for the sake of the expressive feeling conveyed” (Excerpt 19) (Bach C. P. E., 1753, 16).

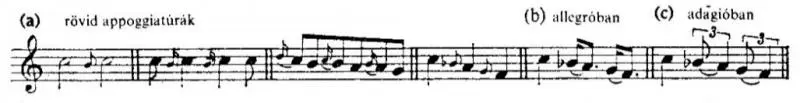

Excerpt 19: Appoggiaturas and their execution (Quantz: Versuch, Berlin, 1752)

In late Baroque music, the short version of the appoggiatura also appeared (Excerpt 20), although the notation remained the same (little sixteenth notes). The executed length depends on the musical context: we should try first a long appoggiatura; if it does not work, the short and moderate may follow. If none of these fits harmonically into the music, we should seek another ornament or even none. “It is only natural that the invariable short appoggiatura should most often appear before quick notes and played so fast that the ensuing note loses hardly any of its length. It also appears before long notes or with syncopations, [also to] fill in leaps of a third. But in an Adagio the feeling is more expressive if they are taken as the first quavers of triplets and not as semiquavers” (Bach C. P. E., 1753, 13-14).

Excerpt 20: Short appoggiaturas

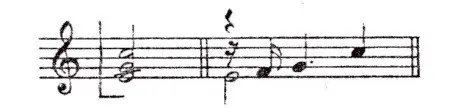

The acciaccatura can be either simultaneous or passing (Donington, 1978). In the simultaneous case, the main note is sounded together with its auxiliary note of dissonance, which should be immediately released, while the main note continues to sound. It is primarily used on the harpsichord, producing an effect of sudden sharpness. It can also be effective on the piano, resulting not in a mere grace note but a snap effect simultaneously executed with the bass.

The passing acciaccatura is an auxiliary note struck between two main notes a third apart, which is released (not too quickly) in a way that lets the main note on both sides continue to sound (Excerpt 21).

Excerpt 21: Arpeggio with passing acciaccatura

If the dissonance is lingered over, the effect is augmented. The passing acciaccatura is suitable for keyboard instruments and is mostly used to enrich the sound of the harpsichord. Due to its position between two main notes, the passing acciaccatura is always unaccented (Excerpt 22).

Excerpt 22: Passing acciaccaturas and approximate performance suggestions

(J. S. Bach: Partita in E minor, Sarabande BWV 830)

The slide is a stepwise pair of auxiliary notes, regularly taken accented, which delays the main note in the same manner as the appoggiatura. It can resemble the passing acciaccatura if the first note of the slide is held and the second is released as the main note arrives (resulting in holding a third) (Excerpt 23). The slide is executed quicker in allegro and slower in adagio (Excerpt 24).

Excerpt 23: A slide indistinguishable from a passing acciaccatura

Excerpt 24: Slides with the first note held and not held

The trill consists of a main note and an upper auxiliary note, which can be a tone or a semitone above (Donington, 1978). Trill of melodic function (mainly in the 16th and 17th centuries) began with its main note or its upper auxiliary note. Trills of harmonic function were started from the upper auxiliary note only. The harmonic function is especially prominent with the cadential trill. Several Baroque cadences are notated without a trill; it is nonetheless essential to play it on the dominant harmony to enrich the cadence with an unmarked element of suspense. The dissonance above the dominant is impactful only if it starts with a long upper auxiliary note (Excerpt 25).

Excerpt 25: Cadential trill initiated from a long upper auxiliary note

“A trill, wherever it may stand, must begin with its auxiliary note. […] If the upper note with which a trill should begin, immediately precedes the note to be trilled, it has either to be renewed by an ordinary attack, or has, before one starts trilling, to be connected, without a new attack, by means of a tie, to the previous note” (Marpurg 1755, p.55) (Excerpt 26).

Excerpt 26: Solutions for a trill with an upper auxiliary note

The speed of the trill is determined by the character of the piece. It is important to not play entirely similar notes to preserve the resemblance to speech in the performance, which is the foundation of Baroque performance. The trill can be played with two terminations; one is the note of anticipation inserted before the ensuing note (Excerpt 27), and the other is the turned ending (Nachschlag) (the sounding of an auxiliary note a tone or semitone below the main note) (Excerpt 28) Either should always be played, whether it is notated or not. The note of anticipation may be connected or separated. “The end of each trill consists of two little notes, which follow the note of the trill and which are made at the same speed […] sometimes these little notes are written […] but when there is only the plain note […] both the appoggiatura [preparation] and the termination must be understood” (Quantz, 1752, 7).

Excerpt 27: Trill with a note of anticipation

Excerpt 28: Trill with a turned ending

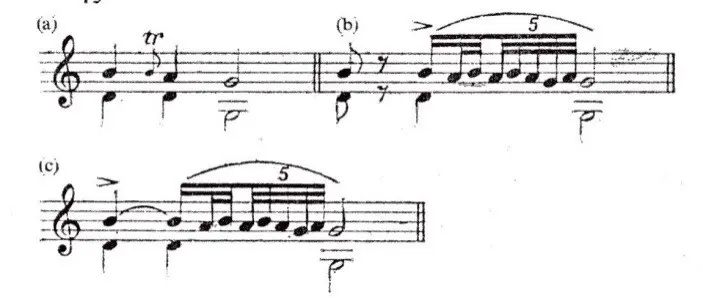

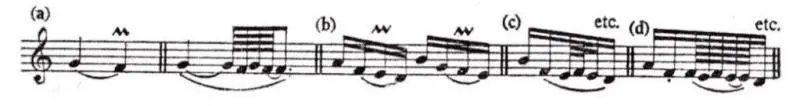

The half-trill (Pralltriller) is an accented ornament which consists of two repercussions, that is, four notes, starts from the upper auxiliary, and the last note, which is the main note, is held in plain (Donington, 1978). More than four notes may also be played, but not as many as to prevent the main note from sounding clearly at the end. Half-trills require no ending. At a high speed, it can happen that the half-trill turns into an inverted mordent, the Schneller, and gets reduced from the main note to three notes (Excerpt 29).

Excerpt 29: Half-trill turning into Schneller at speed

Continuous trills on long notes may start on the main note, but the start is on the beat. There is no necessity for an ending, but if made, it should be a turned ending.

The mordent (from the Italian mordente, biting) is an ornament which comprises a rapid alternation between a main note and a lower auxiliary a tone or semitone below (Donington, 1978). This ornament is of rhythmic function, starts on the accented main note, and can be played diatonically or chromatically. In fast pieces, it is difficult to execute (as with the half-trill), but the goal should be the on-beat execution (Excerpt 30). “The mordent is of all ornaments the most freely introduced by the performer into the bass, especially on notes at the highest point of a phrase, reached either by step or by leap, at cadences and other places, especially when the next note stands at an octave below.” (Bach C. P. E., 1753, 14).

Excerpt 30: Proper execution of the on-beat mordent for the left hand

The turn (Doppelschlag) is a circling around a main note by upper and lower auxiliary notes a tone or a semitone away (Excerpt 31). The turn may be accented, as an on-the-beat ornament with a melodic or harmonic function, or unaccented, as a between-beat ornament with a melodic function. There is an irregular turn starting on the main note, then behaving like a standard turn, circling around the main note (the turn does not fall on the beat, however).

Excerpt 31: Accented and unaccented (irregular) turn

The springer is an ornament made up of a changing note, which is melodic in character and is always unaccented. In essence, the main note is followed by the upper or lower auxiliary, which returns to or crosses the main note (Excerpt 32).

Excerpt 32: Upper and lower springer

Excerpt 33: Note of anticipation

The note of anticipation is similar to the springer, but here the second note is anticipated by the unaccented ornament, thus doubling it (Excerpt 33).

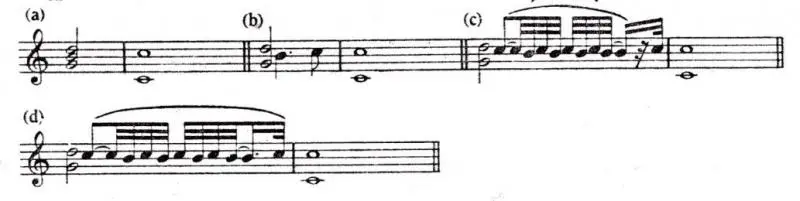

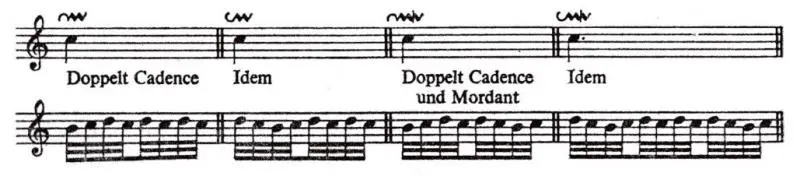

Compound ornaments are the result of two or more ornaments being linked, such as appoggiatura+mordent, Schleifer+trill (ascending trill), Doppelschlag+trill (descending trill) (Excerpt 34).

Excerpt 34: Ascending and descending trills

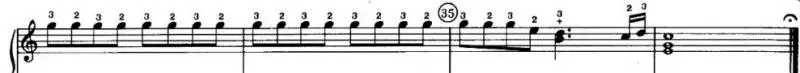

A combination of the irregular five-note turn and the accented upper trill is referred to as double cadence (Excerpt 35).

Excerpt 35: Cadential formula, which denotes the combination of the turn and trill (double cadence)

Closing Remarks

“Musical execution may be compared with the delivery of an orator. The orator and the musician have, at bottom, the same aim in regard to both the preparation and the final execution of their productions, namely to make themselves masters of the hearts of their listeners, to arouse or still their passions, and to transport them now to this sentiment, now to that. […] As to delivery, we demand that an orator have an audible, clear, and true voice; […] that he aim at a pleasing variety in voice and language […]. He must express each sentiment with an appropriate vocal inflexion, and […] he must assume a good outward bearing. […]

Good execution must be first of all true and distinct […], rounded and complete […], easy and flowing […], and varied. […]

Finally, good execution must be expressive‚ and appropriate to each passion that one encounters. […] And since in the majority of pieces one passion constantly alternates with another, the performer must know how to judge the nature of the passion that each idea contains, and constantly make his execution conform to it. Only in this manner will he do justice to the intentions of the composer […].

Each instrumentalist must strive to execute that which is cantabile as a good singer executes it” (Quantz, 1789, 25-29).

“Music and rhetoric are closely related. Both art forms are defined by time; the success of a speech, in the same manner as the effect of music, depends greatly on interpretation; and both musicians and orators follow the same goal: to win over the audience” (Ahlgrimm, 1968, 40-49).

References

- Ahlgrimm, Isolde (Transl. Zák Ferenc) (1968): Retorika a barokk zenében [Die Retorik in der Barockmusik]. in: Régi zene 2. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest (1987, ed. Péteri Judit) 40-49.

- Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel (1753): Versuch über die wahre Art das Klavier zu spielen, I. 3, 4, 7, 12, II. 4-14, 16, 23, III. 5, 28.

- Couperin, Francois (1716/1717): L’Art de toucher le clavecin, Paris, 22.

- Diruta, Girolamo (1593/1609): Il Transilvano, Dialogo sopra il vero modo di sonar organi & istromenti da penna, Venice, 1. 6.

- Dolmetsch, Arnold (1915): The Interpretation of the Music of the XVII and XVIII Centuries, London, Novello and Oxford University Press, 364.

- Donington, Robert (Transl. Karasszon Dezső) (1978): A barokk zene előadásmódja [The Interpretation of Early Music]. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest

- Frescobaldi, Girolamo (1615-16): Toccare (prologue), Rome

- Fytika, Athina (2004): A Historical Overview of the Philosophy Behind Keyboard Fingering Instruction from the Sixteenth Century to the Present

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254673276_A_Historical_Overview_of_the_Philosophy_Behind_Keyboard_Fingering_Instruction_from_the_Sixteenth_Century_to_the_Present - Jakab Hedvig (2007): Ujjrend, artikuláció, díszítés [Fingering, articulation, ornamentation]. Magyar Zene, 2007. 4. 411-428.

- Lindley, Mark and Boxall, Maria (1992): Early Keyboard Fingerings: a Comprehensive Guide, Schott, London

- Lohmann, Ludger (Transl. Karasszon Dezső) (1987): Billentyűs technika és régizene-játék [Keyboard Technique and Early Music Playing]. Muzsika 30. 9. 33-37. Hungarian translation based on: Ludger Lohmann (1982) Studien zu Artikulationsproblemen bei den Tasteninstrumenten des 16-18. Jahrhunderts, Kölner Beiträge zur Musikforschung, Publisher: G. Bosse

- Marpurg, Friedrich Wilhelm (1755/1765): Anleitung zum Clavierspielen, Berlin, I. 7, 29, 55.

- Mattheson, Johann (1740): Grundlage einer Ehren-Pforte, Hamburg, 328.

- Neumann, Frederick (1983): Ornamentation in Baroque and Post-Baroque Music, Princeton University Press

- Oortmerssen, Jacques van (1998): A Guide to Duo and Trio Playing, Boeyenga Music Publications

- Oortmerssen, Jacques van (2002): Organ Technique, Göteborq Organ Art Center

- Quantz, Johann Joachim (1752): Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen, Berlin, Johann Friedrich Voß Verlag VII, 4., VIII. 3-5., IX. 7.

- Quantz, Johann Joachim (Transl. Péteri Judit) (1789): Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen, Breislau, A jó előadásról az éneklésben és a hangszerjátékban általában [About Good Performance in Singing and Playing Instruments in General]. In: Régi zene 2. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest (1987, ed. Péteri Judit) 25-29.

- Tosi, Pier Francesco (1723): Opinioni, English translation. In: Galliard, Johann Ernst (transl.) (1743): Observations on the Florid Song, London, 32.

[1] Lombard rhythm: a series of note pairs of syncopated musical rhythm in which a short, accented note is followed by a longer, unaccented one.

[2] It must be added that some sources contain finger numberings which are wildly different from the current practice, for example in Ricerca by Erbach we find (from below to above): left 1 2 3 4 5 and right 6 7 8 9 10, or in manuscripts by English Virginalists: left 1 2 3 4 5 and right 1 2 3 4 5

[3] In the 19th century, certain changes were implemented to address the requirements of heel use. Pedal keys became parallel to the ground or even elevated slightly towards the heel. In English-speaking areas, additional changes were implemented. Concave and radial pedal forms were introduced to facilitate the use of the heel.

[4] R=right foot, L=left foot.

[5] The double stroke appeared in sources by English Virginalists.

[6] It is impossible to connect different embellishments with the diverse symbols. It can be presumed that all symbols had the same meaning as the double stroke.