Author: Zoltán Óváry

DOI: 10.5434/9789634902263/13

Abstract

Nowadays teaching materials, pieces of music and methods of teaching guitar are widely available, yet experience has shown that most Hungarian teachers still use only national learning content. Their choosing from the slowly but gradually broading materials depends on their professional experience or previous studies. This study examines the most widely known multi-volume guitar teaching materials from an objective point of view. This analysis classifies musical pieces on the basis of their content. The purpose is not to pass judgment but rather to help in assessing the materials through a comprehensive methodological system.

Keywords: Classical guitar, music material analysis, Szendrey-Karper, Nagy–Mosóczi, Sándor Suba

Foreword

Those who have been or will be guitar instructors in a music school have surely asked: “what to teach from”? The decision is inevitable at some point because all teachers find a suitable method, series, or collection. The choice can be assisted by methodological studies of teacher training institutions, which provide an insight into pedagogical processes and analyse guitar textbooks extensively, but others’ opinions might also be helpful. Teachers can later see themselves whether the choice they made was the right one. If they find joy in their work and success with their students, the choice was indeed the right one, but otherwise they have no option but to modify their ideas of teaching and their curriculum.

Either way, it is difficult to choose beforehand. Professional experiences and discourses show that the choice of curriculum for teachers is mostly motivated by subjective factors. It is an interesting question as to what extent teachers familiarise themselves with a textbook before using it. Is there an objective explanation for the textbook or publication choice besides mere impressions, enthusiasm about the included pieces, and children’s suspected or actual attitudes towards the curriculum? Does teachers’ theoretical and professional self have a say?

This seemingly rhetorical question is topical because instrumental methods lack a widely accepted system of analysis. Certain theses of textbook analysis can be implemented here, but many of the aspects (Dárdai, 2002) are irrelevant to the mostly sheet music-based curriculum of music pedagogy. An exhaustive study of instrumental textbooks has been unprecedented. The quantitative measurement of music pedagogy has been limited to ability or attitude analyses on larger populations or samples. In Hungary, several studies in relation to the Kodály concept attempt to prove the influential theoretician’s theses.

This study analyses the characteristics and classification of musical pieces and exercises in multivolume guitar textbooks which are in current use based on pedagogical experiences and teaching practices. The choice of focusing the analysis on multivolume guitar textbooks is because they take a complex path, guide children throughout the entirety of their studies, and are thus comparable. In the investigation, I created different content categories and compared the frequency of their occurrences. The goal of the analysis has not been the creation of an ordering or judgement over which textbook is “usable or not”. Instead, I have been motivated by curiosity and the possibility of helping those who use these guitar textbooks and wish to get a comprehensive picture of the existing publications. I must add that the study is the most informative to those who know these series and their content in some form.

Types and Categorisation of Guitar Textbooks and Pedagogical Resources

The repertoire of didactic material is growing dynamically, mostly in two major directions. One consists of textbooks (or collections resembling textbooks) and the other comprises collections of pieces intended to a determined age group, skill level, or process. This study addresses the first of the two. Textbooks show an effort towards complexity. Their goal is to make the sounding and performance of music perfect, and contain etudes as well as preparatory and assistive exercises corresponding to the individual methodology.

Textbook series can have one or multiple volumes. This seemingly simple and banal distinction provides an important latent information about the content, nevertheless. In going through the publications, it is clear that both types have similar sections. One-volume guitar textbooks are designated to a certain segment of the learning curve, usually the introductory part. It can be concluded that editors of one-volume textbooks generally deem the instruction of beginners the most important and address in considerable detail the introductory phase of learning but do not consider it necessary to devote resources to later phases.

Authors of multivolume textbooks provide a comprehensive educational structure which covers the entirety of music education. The volumes contain various exercises and musical pieces for any stage of development or performance (according to the intention). There are two important factors which create a distinction between multivolume series.

The first factor is the presence of textual instructions. Some instructive materials are designed to also support independent learning. This is not an arbitrary distinction. The author/editor generally decides the nature of the publication to be created beforehand. Textbooks which aid autodidactic learning contain more textual instructions and detailed explanations. This is the aspect in which the three analysed publications differ the most. Although all three are designed for music schools, there are notable differences in the detailing of exercises and theories. The other important factor to be considered is the extent to which the textbook includes the author’s own compositions as opposed to other composers’ works.

Introduction of the Analysed Guitar Textbooks and Materials (in order of publication)

László Szendrey-Karper: Guitar Exercises and Pieces (Gitárgyakorlatok és darabok)

The contributions to pedagogy by László Szendrey-Karper, who is widely considered to be the greatest figure in Hungarian guitar performance, could be described at length. We know unproportionally more about his textbook series than about the other two, mostly because his pioneering work has been studied by many (including the author of this study) since his death.

The novelty in his music pedagogical activity was related to the dynamic development of Hungarian guitar performance and pedagogy in the second half of the 20th century thanks to him. He took advantage of the music education reform in 1951 (Breuer, 1985), which centralised the management and development of music education. It was at that point when the guitar, which was mostly known for the performance and instruction of popular music at the time, was included in the mainstream of classical, standardised, and methodical music education.

One of Szendrey-Karper’s predecessors was Barna Kováts. He was the first Hungarian guitar instructor who researched, performed, taught, and occasionally even transcribed pieces by 19th-century virtuosos as well as Baroque and Renaissance masters. His own compositions are still included in the repertoire of Hungarian guitar performers (Déri, 2007). He published his preliminary and not overly successful guitar textbook in 1956 (Kováts, 1956), in which the “what” and “how” were completely confounded. The same publication comprised methodology, repertoire, and instructions about technique and musical expression. His work was influenced by Bruno Henze’s guitar textbook (1950), as evidenced by the similarities in structure and editing as well as by the inclusion of textual explanations and photographical illustrations in both. However, Szendrey-Karper’s curriculum is more detailed. He devised a methodology (1971) for instructors. In the foreword, he expresses his intent to rely on the pedagogical propositions put forward by Kodály and Bartók. The eight-volume series titled “Guitar Exercises and Pieces” (1980–1985), based on the methodology, was intended for students and is analysed in this study.

Szendrey-Karper’s ars poetica was to present different periods of style as exhaustively as possible and to include a wide repertoire of Hungarian folk songs and contemporary music into music education. He did not compose many pieces besides Bartók transcriptions and folk song arrangements but involved another contemporary composer (László Borsody) into the expansion of the classical guitar repertoire (Fodor 1991).

He wished to provide others with the opportunity to learn polyphonic play and two-voice or multi-voice performance with bass accompaniment by researching and categorising Renaissance and Baroque works for the lute and vihuela. Most pieces in the series were composed in the first half of the 19th century in Paris or Vienna according to the Viennese Classical style. Renowned performers and composers of the period, such as Carulli, Carcassi, Sor, Giuliani, and Aguado, devised methodologies for guitar instruction. Consequently, their works can be used at any stage of music education, from beginners to advanced players. Szendrey-Karper implemented and published in his collection the most important and valuable pieces.

The first volume in the series features various folk songs. Children’s songs and folk songs are widely known, which makes their performance easier. The melodies were later appended by accompanying voices. According to Szendrey-Karper’s theory, folk songs provide a connection to two additional styles. The ancient layer of folk music and early Hungarian melodies provide a gateway to Renaissance music, while the arrangements resemble in their sound and tone the music by 20th-century Hungarian composers, with special regard to Béla Bartók.

Arrangements of dances and melodies from the 16th and 17th centuries and of contemporary pieces are introduced at the halfway point of guitar instruction, but late Renaissance polyphonic pieces are only present in the last volumes. These works presuppose a student with practice and advanced knowledge in music theory and technique. The same applies to Baroque pieces, which pose a great challenge even to intermediate and advanced students due to their complex structure and motoric character requiring concentration.

Szendrey-Karper’s series contains exercises and musical pieces only, which is why it is primarily a collection of exercises and pieces and not a traditional introductory guitar textbook. This, however, does not mean incomparability with other publications because the nature of the practical use is similar in all cases.

It is also worth mentioning that the eight volumes do not exist independently. They are based on Szendrey-Karper’s methodology, published earlier (1971), which complements the collection with instructions for teachers. Furthermore, the methodology was also accompanied by the music school curriculum which was introduced in 1981, and is not in force anymore, as it comprised the content of the eight volumes almost exactly. Based on a small-sample survey, the collection is still popular in guitar education as 80 percent of the surveyed instructors use it in their daily teaching (Óváry, 2014).

Nagy–Mosóczi: Guitar Textbook (Gitáriskola)

The guitar textbook from the joint work by Erzsébet Nagy and Miklós Mosóczi was published almost at the same time as Szendrey-Karper’s educational material. The five volumes by Nagy and Mosóczi contain as much as 787 numbered exercises and musical pieces. The scope and structure of the collection are comprehensive with respect to technical skill improvement and knowledge of styles and repertoire. The series is unique in that it wishes to keep up with the most current music pedagogical methods. It was certainly influenced by predecessors’ works with respect to references, inspirations, and the intention of perfection. There are parallels between it and Szendrey-Karper’s collection because both are based on children’s songs and folk songs and are also similar in the choice of classical composers and modern pieces. However, the Nagy–Mosóczi collection surpasses Szendrey-Karper’s series in many respects. The large number of musical pieces enables stylistic diversity. Furthermore, chamber music pieces are included, even with the participation of other instruments. The possibility of selection is larger and the methodological repertoire is also wider due to the characteristics.

In addition, the instruction of notes begins with the pentatonic scale, which is more suitable for the guitar than the major and minor scales. Novel elements as well as rhythmic and melodic improvisations are also included. The textbook does not contain detailed textual instructions for neither the instructor nor the student but presupposes the presence of a trained teacher. The textbook has not been part of empirical studies so far, but it is presumably the most popular educational material in Hungarian guitar education.

Sándor Suba: Textbook of the Classical Guitar (A klasszikus gitár iskolája)

The third series to be analysed is the most recent one, created by Sándor Suba from Debrecen. At the moment, six of the planned eight volumes are available. Following the predecessors, the author found it important to include Hungarian folk songs into guitar instruction but also had the objective to introduce innovations, enrich the curriculum with theoretical knowledge, and expand the classical guitar repertoire as composer. Interestingly, his compositions not only enhance the repertoire but also create a new style. Guitar textbook authors have complied the collection from their own works before. One of the examples is the Argentinian Julio Sagreras’s (1922) seven-volume textbook, which is regularly used by instructors. It is easy to see that the method, which originated in the early days of classical guitar performance, is intended to correspond to the principle of graduality, is concise and structured in the introduction of chords, and contains various enjoyable pieces. Conversely, its mostly Classical and post-Romantic musical material becomes monotonous after a while because technical improvements are not accompanied by an expansion of musical forms.

A sort of “post-Classical” and post-Romantic sound can also be traced in Suba’s guitar textbooks, but with a modern interpretation and a novel musical sentiment. The etudes and character pieces prescribed by the author make it possible for students to encounter the most suitable piece for any developmental stage, which makes the search for (possibly) suitable compositions elsewhere obsolete. According to the author, modern pieces which are supposed to be appealing in earlier textbooks are far from young people today.

The collection also makes use of modern technical possibilities. The series has a website, where audio material is available and can be downloaded if necessary. Moreover, the author intends to include theoretical education for guitar performance into the series to enable autodidactic learning.

Classification of Works in the Publications by Type

The works in the collections can be categorised into two major types. Usually, there is a clear distinction between exercises and musical pieces. The former category consists of tasks of skill improvement and musical literacy, which sometimes can even be executed without the instrument. The latter category comprises actual music to be performed.

Exercises:

- Rhythm exercise: exercise with the primary objective of teaching rhythmical knowledge for instrumental performance and musical literacy. Often the exercise is not instrument-specific and can be performed knocking or clapping.

- Reading exercise: exercise designed to improve sight reading. It is similar to rhythm exercises because it does not require instrumental play necessarily. Obviously, it is up to the teacher’s discretion to decide the form of execution. Possibilities include: singing (saying) the name of the note, using solfeggio, writing down the name of the note, and even playing.

- Technical exercise: instrument specific task with the objective of manifest skill development in relation to guitar performance. It can be aimed at the activity of a hand or fingers, but exercises designed to master intonation or tone are also included in the category (e.g., scale).

- Creative exercise: rare exercise type only featured in guitar textbooks which put an emphasis, besides musical literacy and instrumental performance, on students’ ability to have individual musical thoughts, to improvise, and to compose pieces themselves. The exercise is mostly introduced in a playful manner. It is the student’s task to complete a melodic excerpt or rhythmic sequence independently or based on the teacher’s instructions. There is a choice for the student to perform the completion on the instrument or write it in the space left blank.

Musical pieces:

- Children’s songs: songs composed usually in children’s language, with small ambitus, taught in kindergarten or lower primary education.

- Folk songs

- Etudes: gradual transitions between performance pieces and technical exercises. However, the execution and character of the composition is closer to a piece performed on stage. It is an interesting feature that they focus on a certain technical segment (or segments) of guitar performance. Their classification is easier if the composer specifies the etude genre in the title, but the score generally reveals an etude due to the schematic rhythm.

- Performance pieces: pieces with the objective of stage performance and musical experience for the student and the audience. Usually, they are based on the expertise built up in previous technical and other exercises. Pieces with Fantasia in the title or which belong to programme music can be categorised as such. Their scores are more diverse than those of etudes.

- Chamber music pieces: authors (editors) of certain instrumental textbooks put an emphasis on collective music performance. Such works can be primarily categorised based on the sheet music. However, canons and simple solo pieces for beginners also belong to this category if the teachers’ appendix contains an accompanying voice.

The categorisation requires a quantitative, scholarly, and professional yet empathetic attitude. The distinction is made easier if the composer specifies the nature of the piece (in the title, for example). However, often it is up to the analyst to decide and “perceive” the characterisation. The most difficult distinction is between performance pieces and etudes. The gradual transition between the two on the guitar makes it almost impossible to judge solely from the sound or sheet music. This is especially true for Classical pieces, whereby the titles often refer to the character. In dubious cases, research about the original source could resolve the problem, but such manifest categorisation might not reveal the actual role of the given musical piece.

It is common to encounter classical works to be demonstrably included into the guitar textbook from an etude collection. Nevertheless, it also occurs frequently that they are put into their new place as contextless pieces. In this case, the original composer and the editor of the pedagogical publication have seemingly different objectives about the inclusion of the piece. The presentation of works from various places by different composers in modern guitar textbooks enhances diversity and does not serve the original technical and musical concept. Therefore, since these are the most “audience friendly” compositions of the original collection, they are categorised as performance pieces.

The centre of interest is the distribution of certain pieces in the series. I arrived at the categorisation of pieces and exercises after analysing the content of the publications (Figure 1). Since there are differences in the number and content of volumes, the analysis is conducted with percentage distributions, based on which the differences, similarities, and potential analogies can be uncovered. The unit is a numbered element (piece or exercise). Several exercises have multiple sections, such as a), b), c, etc., which are considered as one element in the statistics because the pedagogical concept (and not the length) is in focus.

Nagy–Mosóczi guitar textbook

|

|

Rhythm exercise | Reading exercise | Technical exercise | Creative exercise | Children’s song | Folk song | Etude | Performance piece | Chamber music piece |

|

N-M. I. |

8% |

11% |

19% |

3% |

8,5% |

14% |

12% |

15% |

9,5% |

|

N-M. II. |

5% |

7% |

11% |

7% |

- |

2% |

15% |

51% |

4% |

|

N-M. III. |

- |

3,5% |

12,5% |

6% |

- |

2% |

19% |

49% |

8% |

|

N.M. IV. |

- |

- |

11% |

- |

- |

- |

24% |

53% |

12% |

|

N-M. V. |

- |

- |

18% |

- |

- |

- |

21,5% |

60,5% |

- |

László Szendrey-Karper: Guitar Exercises and Pieces

|

|

Rhythm exercise | Reading exercise | Technical exercise | Creative exercise | Children’s song | Folk song | Etude | Performance piece | Chamber music piece |

|

SZKL I. |

- |

23% |

16,5% |

- |

11% |

33% |

16,5% |

- |

- |

|

SZKL II. |

- |

3,5% |

13,5% |

- |

- |

10% |

53% |

20% |

- |

|

SZKL III. |

- |

- |

2,5% |

- |

- |

- |

- |

97,5% |

- |

|

SZKL IV. |

- |

4% |

32% |

- |

- |

14% |

- |

50% |

- |

|

SZKL V. |

2% |

- |

7% |

- |

- |

16% |

- |

75% |

- |

|

SZKL VI. |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

4,5% |

95,5% |

- |

|

SZKL VII. |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

9,5% |

90,5% |

- |

|

SZKL VIII. |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

100% |

- |

- |

Sándor Suba’s guitar textbook

|

|

Rhythm exercise |

Reading exercise |

Technical exercise |

Creative exercise |

Children’s song |

Folk song |

Etude | Performance piece |

Chamber music piece |

|

Suba I. |

3% |

19,5% |

12% |

3,5% |

26% |

13% |

20% |

- |

3% |

|

Suba II. |

2,5% |

14% |

3,5% |

6,5% |

4% |

30% |

28,5% |

8% |

3% |

|

Suba III. |

- |

16% |

12% |

6% |

1% |

14,5% |

36% |

11% |

3,5% |

|

Suba IV. |

- |

28% |

2% |

4% |

- |

- |

16% |

43% |

7% |

|

Suba V. |

- |

29% |

12% |

- |

- |

- |

17% |

38% |

4% |

|

Suba VI. |

- |

25,5% |

24,5% |

- |

- |

- |

24,5% |

20,5% |

4% |

Figure 1: Percentage distribution of content in textbooks (author’s compilation)

* = highest value in the textbook

If the distribution is analysed across the two major categories (exercises, musical pieces), it can be seen that the majority of the curriculum is made up of etudes and performances. Such pieces are generally present from the beginning to the end of the series (and education). Presumably, the goal is a diverse repertoire and the familiarisation with stage performance and extroverted music performance, which is why several exercises and simple pieces revolve around this. Musical pieces are limited to children’s songs and folk songs at first, but the emphasis mostly shifts through etudes to performance pieces and chamber music compositions.

Pedagogical practice would have suggested to present in the first (introductory) volume children’s songs and folk songs in the largest proportion. However, they are only in “first place” in one case (Szendrey-Karper). They are exceeded by technical exercises and etudes, respectively. One perspective, however, points at the dominance of folk music. It was only for practical reasons (wider scope of analysis) and the rise in difficulty between the two styles why the distinction was made between folk songs and etudes. Once etudes and folk songs are combined, they constitute the highest value invariably across volumes (Figure 2).

|

|

Rhythm exercise |

Reading exercise |

Technical exercise |

Creative exercise |

Children’s song |

Folk song |

Etude | Performance piece |

Chamber music piece |

|

Nagy–Mosóczi. I. |

8% |

11% |

19% |

3% |

8,5% |

26% |

15% |

9,5% |

|

|

Szendrey-Karper I. |

- |

23% |

16,5% |

- |

11% |

49,5% |

- |

- |

|

|

Suba I. |

3% |

19,5% |

12% |

3,5% |

26% |

33% |

- |

3% |

|

Figure 2: Percentage distribution of content in textbooks with the combination of the folk song and etude categories (author’s compilation)

* = highest value in the textbook

Notably, Volume VI of Suba’s textbook features the highest proportion of reading exercises (designed to improve sheet music interpretation). This may be explained by the author’s concept of introducing different technical and skill improving exercises simultaneously with musical pieces, which keeps students constantly stimulated with respect to theory, as well. The other explanation is rather practical. The different volumes, so to speak, are of similar length in terms of pages. As the student progresses through the volumes, the pieces become longer. The increasing quality and length result in fewer pieces in a volume. At the same time, the number and length of different reading, harmonic, or sound recognition exercises remain mostly unchanged. This is easy to see once we consider the count of pieces and reading exercises in Suba’s volumes instead of percentages. The number of exercises is usually on the rise, while performance pieces increase then decrease in quantity (Figure 4).

|

|

Reading exercise |

Performance piece |

|

Suba I. |

35 |

- |

|

Suba II. |

17 |

10 |

|

Suba III. |

18 |

12 |

|

Suba IV. |

28 |

43 |

|

Suba V. |

29 |

38 |

|

Suba VI. |

31 |

25 |

Figure 4: Count of content in Sándor Suba’s textbook volumes (author’s compilation)

The initial increase is due to the shift in focus from children’s songs to performance pieces (and etudes, of course).

The Distribution of Exercises

The number (distribution) of different exercises is also diverse across volumes and series. While the Szendrey-Karper and Nagy–Mosóczi publications have more technical exercises, Sándor Suba’s guitar textbook contains more theoretical exercises designed for sheet music interpretation, which can be executed without the instrument.

Rhythm exercises, which attempt to complement the (supposed) solfeggio education and to enrich the learning process, are difficult to find. They do not necessarily require a guitar and can be used as relaxing or playful exercises. They are more frequent at the initial stage of music education, but their occurrence is not common throughout.

For reading exercises and music literacy tasks, the differences in the distributions between volumes are more significant. While general and instrument-specific sight reading is only deemed important at the beginning of guitar instruction by Nagy and Mosóczi and by Szendrey-Karper, Sándor Suba’s guitar textbook contains exercises to this aim continuously. The latter exceeds the former two in both number (proportion) and diversity. The frequency of reading exercises in the first volume of Guitar Exercises and Pieces by Szendrey-Karper is ambiguous because the various reading exercises also improve other skills at the same time (see the chapter titled “Latent Content and Overlapping Categories”). As volumes progress for the Szendrey-Karper and Nagy–Mosóczi collections, the number of reading exercises gradually decreases until their eventual disappearance.

All three series contain technical exercises in a large proportion. Although the distribution of such exercises varies across authors, the conscious progression throughout the volumes is universal. László Szendrey-Karper’s collection of exercises and pieces contain technical exercises only in the first five volumes due to a conceptual reason: it is only in those volumes where he addresses the technique “intensively”; later volumes contain their practical implementation. Even though it would be possible to “forcibly” find connections in the distributional change of technical exercises across volumes, it can be said that all three collections contain a summarising (or compensating) series of exercises at the end in some form. In the (currently) last volume of the publications by Nagy and Mosóczi and by Sándor Suba, this is present in manifest content, while Szendrey-Karper’s collection has an indicative solution by including a relatively dry series of etudes at the end.

Certain listed categories of exercises and musical pieces are not present in all publications. While guitar textbooks by Nagy and Mosóczi and by Sándor Suba contain every type of content, Szendrey-Karper’s collection lacks exercises designed for chamber music or musical creativity improvement, which is interesting because those are potential ways of enhancing the interaction between student and teacher. There are no definite conclusions to be made, however, because the publication in question is a collection of exercises and pieces and not a guitar textbook explicitly.

The Fluctuation of Exercises and Musical Pieces

It is evident from previous chapters and tables that guitar textbooks and collections are different not just in the distribution of exercises and musical pieces but also in their occurrence across individual volumes (Figure 5). Both technical exercises and pieces are featured with the largest frequency at the beginning of the studies.

|

Nagy–Mosóczi |

|

Volume I | Volume II | Volume III | Volume IV | Volume V |

| exercises | rhythm |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| reading |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| technical |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| creative |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| musical pieces | children’s song |

+ |

|

|

|

|

| folk song |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| etude |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| performance piece |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| chamber piece |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| Szendrey series |

|

Volume I | Volume II | Volume III | Volume IV | Volume V | Volume VI | Volume VII | Volume VIII |

| exercises | rhythm |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

| reading |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

| technical |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

| musical pieces | children’s song |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| folk song |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

| etude |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| performance piece |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| Suba series |

|

Volume I |

Volume II |

Volume III |

Volume IV |

Volume V |

Volume VI |

| exercises | rhythm |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

| reading |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| technical |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| creative |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| musical pieces | children’s song |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| folk song |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

|

| etude |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| performance piece |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

| chamber piece |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

Figure 5: Presence of exercises and musical pieces in given textbook volumes (author’s compilation)

The structure of the two guitar textbooks is similar. In the introductory volumes, all kinds of exercises and musical pieces are present. As the education progresses, the spectrum gets more restricted, and only etudes, performance pieces, and technical exercises remain at the end, with the exception of Suba’s guitar textbook, which also contains reading exercises and chamber music.

Items of Szendrey-Karper’s collection of exercises and pieces display a different pattern. As opposed to the other two publications, the categories in the table seem to be sporadic, due to the different concept. The author does not feature the categories simultaneously but employs specialisation techniques in certain cases (or volumes). Consequently, the given units are homogeneous in character and style. The clustered categories come in “larger doses” for structural simplicity and, importantly, for greater (supposed) efficiency. The analysed categories (mostly etudes) appear and disappear for one or more volumes.

It is not strictly connected to the topic, but it is worth mentioning that the author of this study has conducted a comprehensive analysis and empirical study of László Szendrey-Karper’s Guitar Exercises and Pieces. The small-sample survey exploring the use of certain Szendrey-Karper volumes was initiated due to the diverse and seemingly unordered occurrence of categories as well as the popularity of the collection.

|

|

Vol. I |

Vol. II |

Vol. III |

Vol. IV |

Vol. V |

Vol. VI |

Vol. VII |

Vol. VIII |

| rhythm |

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

| reading |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

|

|

| technical |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| children’s song |

+ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| folk song |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

| etude |

+ |

+ |

|

|

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

| performance piece |

|

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Figure 6: Distribution and count of content in László Szendrey-Karper’s series titled Guitar Exercises and Pieces (author’s compilation)

Twenty teachers responded to the survey, most of whom used the Szendrey-Karper series regularly. Interestingly, the empirical and comparative analyses has concluded that Volume III, which only contains technical exercises and performance pieces, is the most popular and most frequently used among instructors. The marginalisation of Volume II, which comprises etudes and technical exercises necessary for Volume III, is rather puzzling. The phenomenon is likely due to the fact that while Volume II, despite its statistical diversity, mostly consists of etudes (Figure 6), Volume III is a well-calibrated collection with a diverse repertoire which suits the “target group”.

The distribution of content categories across the three series of publications leads us to an interesting conclusion. Practising instructors are right to presume that the student’s knowledge as well as need for knowledge both increase over time. Consequently, guitar textbooks, which are rightly called the textbooks of music education, should constantly increase in content diversity. Yet, the quantitative study reveals that certain categories disappear and are phased out continuously and gradually from the series. At the end of the planned duration of music education, the volumes become homogeneous and can hardly be differentiated from mere collections.

Latent Content and Overlapping Categories

The content categories of publications detailed above were determined based on primary characteristic. However, it is often the case that an exercise or piece also has a secondary (or even tertiary) characteristic, which mostly occurs for pieces and exercises for beginners. The most frequent examples are reading exercises based on children’s songs and reading exercises also constituting technical exercises. The reason is the difference in the author’s concept about the extent of making the content explicit or implicit. The research of overlapping categories requires the above-mentioned scholarly and professional intuitions the most. Overlapping content is present in all volumes but with a gradually declining frequency. Since these aspects could only be described (or illustrated) for all volumes in an overly complicated and not very transparent way, I present the respective results for the first volume of each series.

I have mentioned that there are differences across series in the number of volumes and pieces in them, yet they can still be compared due to the authors’ similar intentions. By the termination of Volume I in each series, the correct posture of the guitar, the proper hand position, and the knowledge necessary for working and practising at home are all available. Students should be able to follow the notes in the score being performed, recognise the necessary rhythmic values for melodic performance, and interpret them on the instrument. They should be able to play monophonic songs in a narrowly defined guitar professional sense, possibly in another key with a key signature or with inserted accidentals. By the end of the volume, students should have encountered polyphonic play (in one way or another). There are some differences in this respect: Suba’s guitar textbook delays the introduction of polyphony somewhat but the simultaneous sounding of multiple notes is still featured in chamber music or arpeggio pieces.

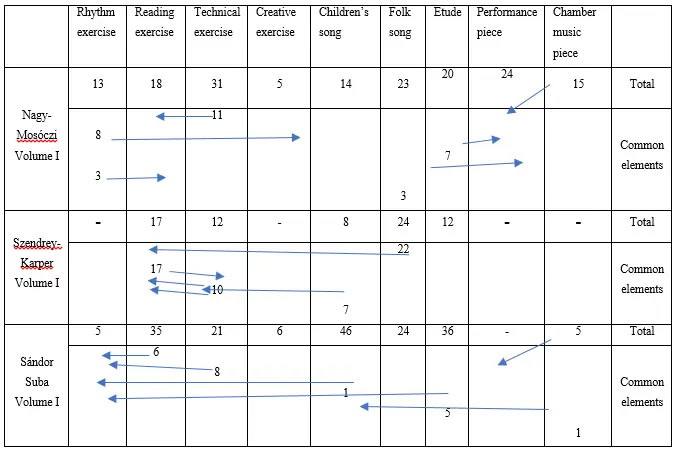

Figure 7: Common elements across categories in the first volumes of textbooks (author’s compilation)

The comparison reveals that, albeit not in the same proportion, all volumes contain at least some musical pieces or exercises which belong to multiple categories. The table illustrating this (Figure 7) shows, below the number of pieces or exercises in the volume, the number of those with a secondary category. The blue lines indicate the orientation of the latent content.

For the Nagy–Mosóczi series, the most common overlaps are between technical and reading exercises, most of them scale exercises. The categorical ambiguity is explained by the difficulty of performing scales, which is a routine exercise only for advanced players. After two or three volumes, such exercises would have been classified as technical only, but beginners often encounter these type of note sequences for the first time.

In the same collection, almost all rhythm exercises overlap, mostly with creative and reading exercises. Rhythm exercises are commonly paired with tasks whereby the student must complete a sequence in writing or clapping/knocking. Children’s first encounter with rhythm notation, which is to be interpreted as musical notes, is also a reading exercise.

Performance pieces are another focal point for secondary content. Several folk songs and etudes also fall into the category. At the beginning of music education, certain (rather serious) folk songs have a “performance” character because they are likely to be performed in student concerts or instrumental presentations. The reason for various etudes to be included in the category is the fact that they were added to the publication not because of their technical message but due to the demand for diversity and their contrasting novelty as opposed to previous items. The etudes in question are mostly classical, which were taken from methods and series of their period individually and were inserted into the analysed publications by the authors. Although the number of pieces for beginners increases constantly, from both Hungarian and international composers, experience from exams and student concerts shows that the discussed works are still performed regularly. Besides the familiarisation with collective music, chamber music pieces were composed (or included in the volume) to enable performance in front of others even for those who cannot accomplish a complex and enjoyable production all by themselves. I present chamber pieces in overlap with performance pieces invariably.

László Szendrey-Karper’s collection of exercises and pieces contains the most overlaps compared to the number of pieces. Besides one type, all categories display multiple overlaps for almost every item. Notably, every reading exercise is also a technical exercise at the same time, and almost every folk song and technical exercise can be classified into the category of exercises designed to improve sight reading. Considering the multiple overlaps even for the one-digit exercises at the beginning of the volume, it is difficult for the researcher not to present professional critique and question the methodological correctness… Nonetheless, it can be said objectively that the folk music material, which is also intended to convey technical skills and aid musical literacy, exceeds any other category.

Comparatively, the first volume in Suba’s series has the fewest category overlaps. Rhythm exercises constitute a collective category for various overlaps. The implicit practice of rhythm is present at several points in the volume. In an unusual solution, instructions with respect to the beat and rhythm are written above the notes. Since other categories contain no or little overlaps, it can be concluded that the volume is divided well in relation to exercises and pieces to be performed, with clearly distinct tasks. Not surprisingly, it is this volume which contains the largest number of items. Interestingly, the latent content creates a category (through the connection between chamber music and performance piece) which is not present in the volume as primary content.

Once the overlaps in content are known, it is interesting to see how the number and relative distribution of pieces compare when multiplicative factors are also included.

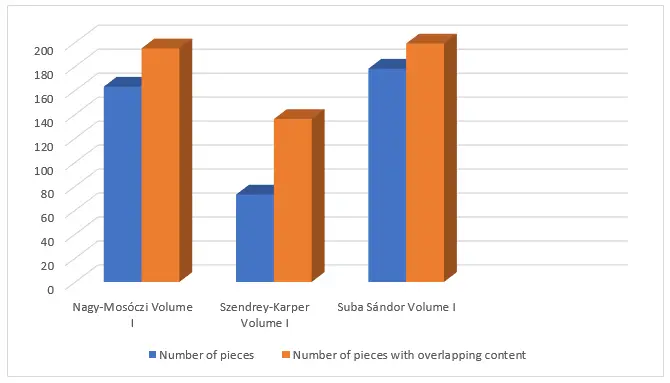

Figure 8: Comparison of primary and overlapping content in certain volumes (author’s compilation)

When comparing the analysed publications in this respect, it is evident that the inclusion of latent content rearranges the proportions substantially (Figure 8). In the calculation, the number of “secondary and tertiary” elements were added to the original item count. Through the inclusion of overlapping content, the figure did not rise as much for the Nagy–Mosóczi and Suba volumes as for Volume I of Szendrey-Karper’s series, where the number almost doubled.

Conclusions, Summary

The quantitative analysis uncovered various interesting connections and unexpected findings. The analysis focused on the content categories of certain guitar textbooks and collections. I approached the topic as an education researcher and curriculum analyst, but the practising guitar instructor in me was also present by following the connections between theory and practice.

The analysed guitar textbooks were selected based on pedagogical experience and the current supply and possibilities. The three selected series were:

- László Szendrey-Karper: Guitar Exercises and Pieces (I–VIII)

- Nagy–Mosóczi: Guitar Textbook (I–V)

- Sándor Suba: Textbook of the Classical Guitar (I–VI)

Two of the three publications are guitar textbooks, namely the Nagy–Mosóczi and Suba series, while the Szendrey-Karper series is a collection of etudes and pieces, which is complemented by a methodological guideline and a (former) curriculum. According to the pedagogical practice, it is possible to compare them as guitar textbooks despite the different terminology.

I created categories based on the volumes. It was important to include each piece or exercise in one of them. The two major categories were the exercises and musical pieces, respectively. I evaluated the material as primary or latent content, which were quantified and their proportions aggregated.

My primary finding is that the curriculum is always centred around performance pieces and stage music, which means children’s songs and folk songs in volumes for beginners. These pieces are the most numerous in both numbers and proportions. There are differences in the distribution of exercises, but all authors favour and overrepresent technical exercises.

Interestingly, certain categories almost or entirely disappear, with the exception of Suba’s guitar textbook.

Szendrey-Karper’s collection has the most overlaps in content. Its almost every item has a secondary, or even tertiary, characteristic. Generally, the more pieces are contained in a volume, the less is the need to compress multiple tasks into one exercise or piece. It is worth considering which option is more fruitful. Presumably, the series with little overlap in content consist of better defined tasks and enable a slower but more thorough progress.

Unfortunately, the scarcity of published, distributed, and widely used guitar textbooks does not permit a longitudinally representative analysis of changes and improvements in content. It is more likely that the research should continue cross-sectionally with international comparisons.

References

- Breuer János (1985): Negyven év magyar zenekultúrája [Hungarian Musical Culture of 40 Years]. Zeneműkiadó, Budapest.

- Dárdai Ágnes (2002): A tankönyvkutatás alapjai, [The Fundamentals of Textbook Research]. Dialog Campus kiadó, Budapest–Pécs.

- Fodor Lajos (1991): A gitáros [The Guitarist]. Hotel Info Kft. Budapest

- Gönczy László (2009): Kodály-koncepció: a megértés és alkalmazás nehézségei Magyarországon, [Kodály Concept: The Difficulty of Understanding and Application in Hungary], Magyar pedagógia 109. 2. szám 169–185.

- Henze, Bruno (1950): Das Gitarrespiel, VEB Friedrich Hofmeister, Leipzig.

- Kováts Barna (1956): Gitáriskola [Guitar School]. Editio Musica, Budapest.

- Nagy–Mosóczi (1980–87): Gitáriskola [Guitar Tutor] I–V., Editio Musica, Budapest.

- Sagreras, Julio Salvador (1922–34): Las Lecciones de guitarra I–VI. Guitar Haritage Inc., Chanterelle, Colombus, Ohio.

- Suba Sándor (2010): A klasszikus gitár iskolája [The Study of Classical Guitar]. (self-published)

- Szendrey-Karper László (1971): A gitártanítás módszertana [The Method of Guitar Teaching]. Liszt Ferenc Zeneművészeti Főiskola, Budapest.

- Szendrey-Karper László (1980–86): Gitárgyakorlatok [Guitar Exercises]: Vol. I–VIII. Editio Musica Budapest.

Websites

- Déri Gábor (2007): A gitár Magyarországon [The Guitar in Hungary]

http://www.kil.hu/cikk_a_gitar_magyarorszagon.php - Óváry Zoltán (2014): Szendrey-Karper László jelentősége a magyarországi intézményesített klasszikus gitároktatás megteremtésében [The Importance of László Szendrey-Karper in Estabilishing the Hungarian Classical Guitar Education]. Parlando 2014/ 4.

http://www.parlando.hu/2014/2014-4/2014-4-05-Ovary-SzendreyKarper.htm